Cyclical Brain Rhythms Drive Key Cognitive Functions

Post by Soumilee Chaudhuri

The takeaway

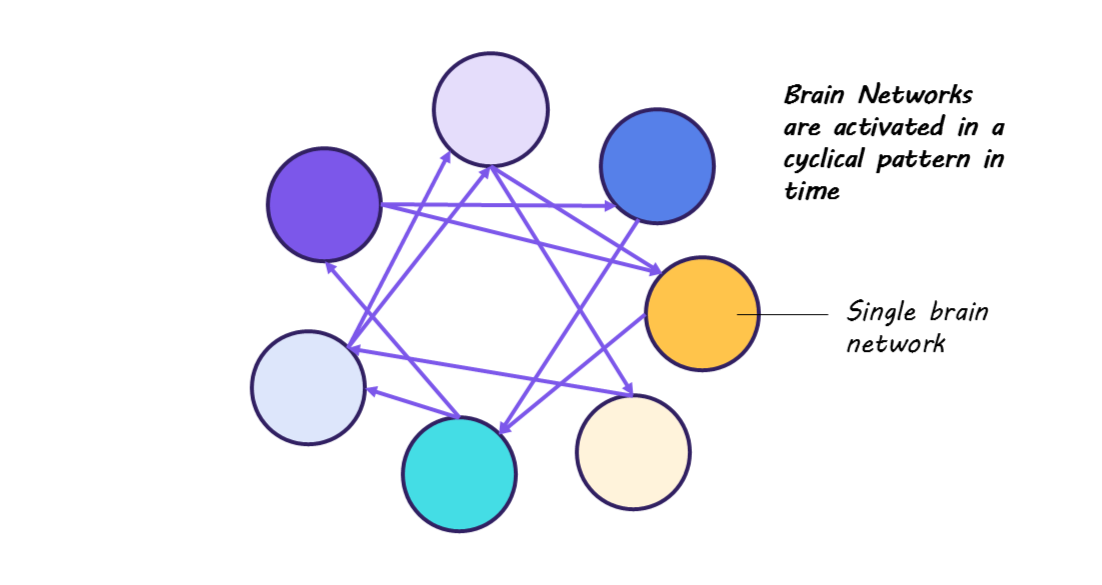

Brain networks carry out day-to-day cognitive functions, such as focusing, remembering, and processing sensory information. The activity in these networks follows a cyclical pattern, with each activation supporting essential cognitive functions.

What's the science?

The human brain carries out numerous cognitive and bodily functions, but it has been unclear how these processes are coordinated over time. Previous studies using different forms of neuroimaging have observed directional relationships in network transitions; however, it remained unclear whether these asymmetries are part of a higher-level organization. This week in Nature Neuroscience, van Es and colleagues analyzed brain imaging data from five independent datasets and revealed that, while individual transitions appear noisy, they collectively form consistent cycles that repeat every 300–1,000 milliseconds, with each network having a preferred position within the cycle.

How did they do it?

The study analyzed brain activity from over 800 participants across five Magnetoencephalography (MEG) datasets. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 88 years and included both males and females. MEG signals were mapped onto the brain’s cortex, divided into 38–78 regions depending on the dataset, to track how different brain areas interacted over time. Using a Hidden Markov Model, the researchers identified 12 recurring brain network states and examined the timing and direction of transitions between these states. They applied a new method, temporal interval network density analysis or TINDA, to detect characteristic sequences of network activations emerging as cycles. The makeup of this cyclical pattern, along with its strength (amount of deviations from the cycle) and speed, were quantified and analyzed for consistency across participants and their relationship with age, cognitive performance, and behavior, showing how these brain rhythms relate to key individual traits.

What did they find?

Identified brain networks followed a cyclical pattern, with cognitive and perceptual networks taking turns in a consistent and coordinated sequence. This sequence or cycle lasted approximately 300–1,000 milliseconds, and the timing and strength of these cycles were linked to age and cognitive performance. The researchers found that older adults showed much slower cycles compared to younger participants. The phase of the cycle also predicted moment-to-moment behavior, including markers of memory consolidation and reaction speed. Finally, additional findings suggested that the rate of these cycles was partly heritable, indicating a biological basis for these rhythms.

What's the impact?

This study provides compelling evidence that the natural cyclical activation of large-scale brain networks underlies essential cognitive functions. These findings shed light on the mechanisms underlying cognitive processes in the brain and highlight the potential for targeting brain network rhythms in interventions designed to enhance cognitive function.