How Does the Brain Overcome Social Exclusion?

Post by Rebecca Glisson

The takeaway

Negative emotions that come from social exclusion can be relieved through emotionally supportive social interaction between two people. During this emotional support, there is synchronized activity in the prefrontal cortex, the brain region involved in emotional regulation, between the person giving and receiving emotional support.

What's the science?

When you are excluded from a social group, it can be challenging to manage the unhappiness and upset on your own and to emotionally regulate. Having someone else to help support and comfort you, which is called interpersonal emotional regulation, may be a more effective way to handle these negative emotions, although this has not yet been studied. This week in Scientific Reports, Zhu and colleagues investigated whether interpersonal emotional regulation is more effective than intrapersonal emotional regulation for managing negative emotions in response to social exclusion, as well as the brain activity that controls these behaviors.

How did they do it?

To study the differences between intrapersonal and interpersonal emotional regulation, the authors had participants experiencing negative emotions after social exclusion events either regulate their own emotions or work with another participant to regulate their emotions. First, participants were shown pictures of someone being excluded by their peers, and then were asked to think about a time they personally experienced social exclusion. Following this, one group of participants was given a strategy to try to regulate their emotions while alone, which simulated intrapersonal emotional regulation. The interpersonal emotional regulation group, on the other hand, was paired with another person who was given a strategy to help the person experiencing social exclusion.

In a second experiment, the authors used functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to measure brain activity while participants were negatively reacting to social exclusion and during the interpersonal emotional regulation afterwards. The authors focused their measurements on the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain that links emotion regulation and social interaction. Both the participants who were experiencing the negative emotions and their paired partners who were helping regulate their emotions were scanned at the same time to study if brain activity was synchronized during interpersonal emotional regulation.

What did they find?

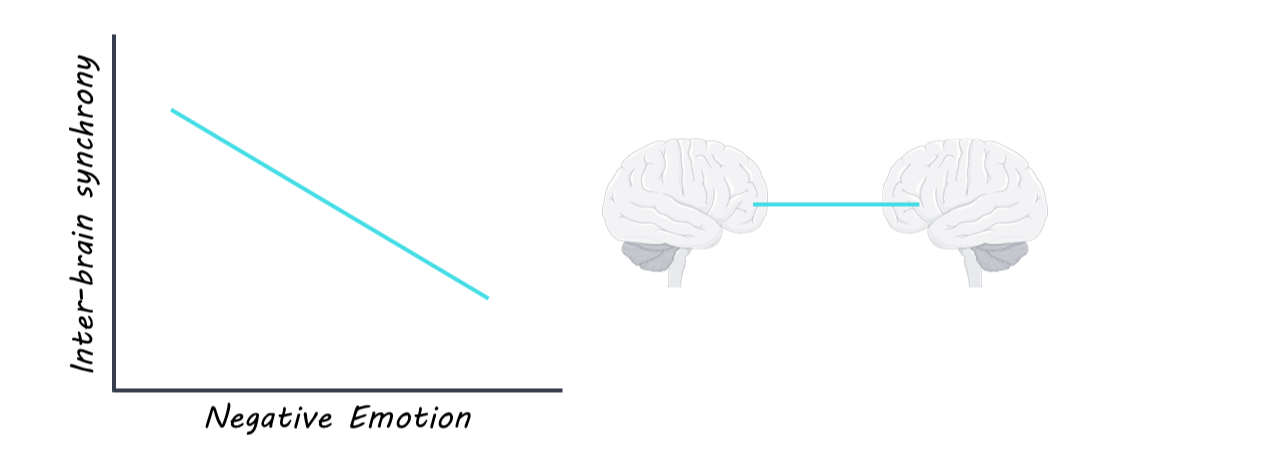

In the first experiment, the authors found that people feeling negatively after social exclusion were better at managing those emotions with someone else than by themselves. This suggests that interpersonal emotional regulation is more effective at relieving negative feelings after social exclusion than working through the emotions alone. In the second experiment, the authors found that the left medial part of the prefrontal cortex is more active while someone is reacting negatively to social exclusion. Then, during interpersonal emotional regulation, they found that the activation of both the emotion experiencer and the emotion supporter was synchronized in the prefrontal cortex. This suggests that synchronization of activity in the prefrontal cortex between two people during interpersonal emotional regulation is the mechanism that leads to better outcomes after social exclusion.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to show that interpersonal emotional regulation is more effective than intrapersonal emotional regulation at reducing negative reactions to social exclusion, and the brain mechanisms involved with this process. These results suggest that empathy is crucial for helping others deal with social exclusion. As social exclusion is common for both children in school and adults in the workplace, and can lead to poor outcomes for both mental and physical health, it is important for studies like these to provide strategies to manage responses to social exclusion.