Rugby Players Show Signs of Neurodegeneration in the Brain

Post by Anastasia Sares

The takeaway

This study reveals that former rugby players have elevated blood levels of a protein called Tau, which is associated with neurodegeneration, underscoring the risks of participating in contact sports where sub-concussive impacts are common.

What's the science?

Rugby is a high-contact sport where players can expect to experience head impacts regularly. Previous research has shown that players of high-contact sports have an increased risk of dementia, specifically Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) – a neurodegenerative disease first made famous in boxers, which can include mood swings, aggression, and memory problems. Studies on the brain tissue of players who have died with CTE show changes in the level of dementia-related molecules, specifically a protein called Tau. This is consistent with the idea that the head impacts and concussions suffered by players may trigger processes of neurodegeneration. However, it is difficult to track these subtle processes in people who are still alive but whose concussions or injuries are far in the past.

This week in Brain, Graham and colleagues were able to show changes in dementia-related molecules in a large sample of ex-rugby players based on a blood sample, along with MRI data showing decreased brain volume and disrupted connectivity.

How did they do it?

Participants included 200 rugby players and 33 healthy controls, on average in their forties, along with a sample of older adults from a separate study, including 69 people with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and their age-matched healthy controls. The authors obtained blood samples from the participants and used precise immunosorbent assays to detect specific proteins. An assay like this uses synthesized immune proteins (antibodies) that normally bind to foreign invading substances. By engineering the antibodies to bind to different proteins instead, they can capture these proteins and analyze the quantity of any molecule they choose. In this case, they were interested in dementia-related molecules such as amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau217, as well as other brain trauma indicators (plasma neurofilament light and glial fibrillary acidic protein). The participants were also scanned with MRI so that the size and shape of different brain regions could be estimated.

What did they find?

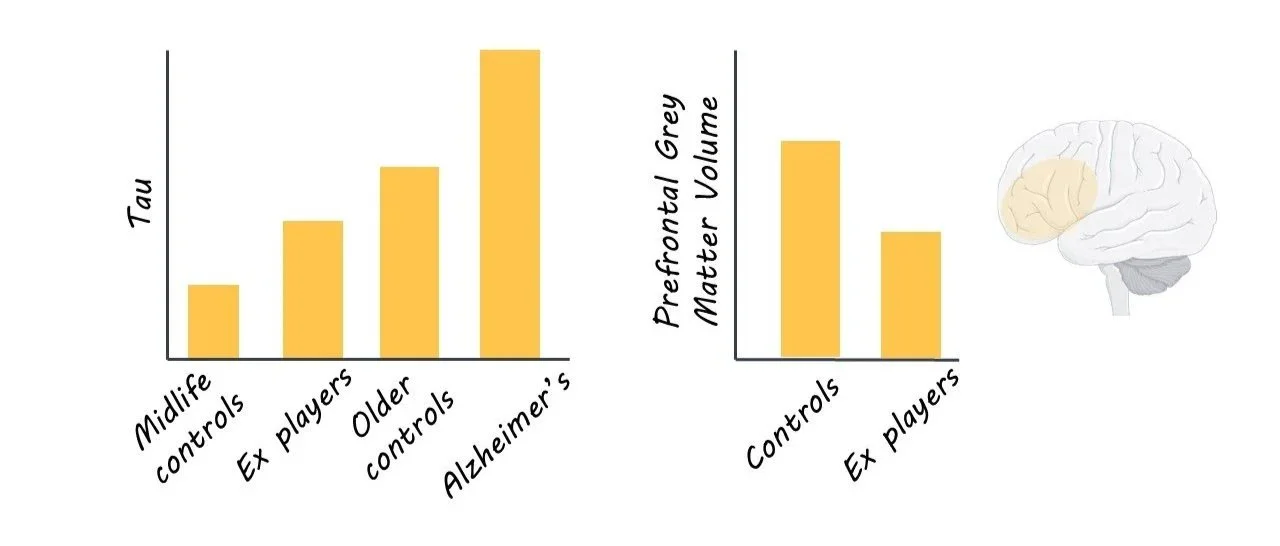

The rugby players had elevated levels of one key molecule involved in neurodegeneration: p-tau217. This increase in p-tau217 was associated with greater odds of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (the clinical/behavioral symptoms of CTE). Alzheimer’s patients, on the other hand, had elevated levels of all molecules, even above the levels of the rugby players.

MRI scans showed that players had lower brain volume in certain areas, like the frontal and cingulate cortex and the hippocampus—areas involved in executive function, emotional regulation, and memory. These changes in brain volume were related to the amount of time spent playing professionally. Finally, greater amounts of p-tau217 in the blood were related to a smaller volume in the hippocampus, a center of emotion and memory formation. It is important to note that these rugby players were recruited by self-referral, and one of the reasons for self-referral could include cognitive concerns. So, the results in this sample may be more extreme than for all rugby players.

What's the impact?

This study shows that rugby players coming in for cognitive concerns do indeed have elevated levels of tau protein, and that this is correlated with structural brain changes that could be part of CTE. Given their risk, it is important to monitor rugby players for signs of cognitive decline, and the methods used in this study are a useful step in developing this monitoring capability.