A Device for Tracking Fluid Exchange in the Brain

Post by Lila Metko

The takeaway

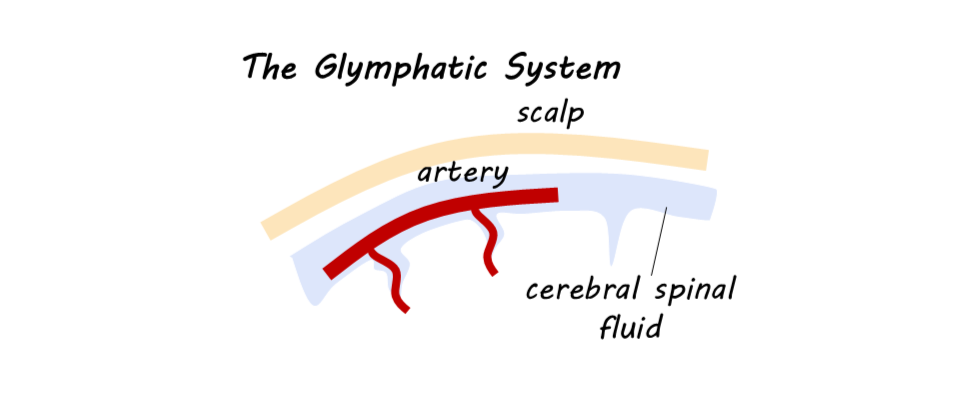

The glymphatic system is a fluid transfer and waste clearance system within the central nervous system (CNS) that supports the clearance of amyloid beta and tau proteins that accumulate in neurodegenerative disease. The authors developed a multielectrode patch, the first non-invasive method in humans to probe the activity levels of the glymphatic system during sleep.

What's the science?

Glymphatic function is a crucial fluid exchange process in the brain, facilitating the conversion of interstitial fluid into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which nourishes cells, regulates the volume transmission of neuromodulators, and is involved in the clearance of unwanted substances, such as amyloid beta and misfolded tau proteins. Glymphatic impairment in animal models has been shown to promote the development of amyloid beta and tau pathology. Additionally, glymphatic impairment is associated with aging, sleep deprivation, traumatic brain injury, and risk factors for neurodegenerative disease, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Glymphatic function has been shown to be more rapid during sleep. Currently, there is no non-invasive, temporally optimal device to monitor glymphatic function in humans. Recently, in Nature Biomedical Engineering, Dagum and colleagues describe a non-invasive device for monitoring glymphatic function in humans.

How did they do it?

The authors conducted two complementary human studies in which participants wore the electrode patch device on the posterior area of the scalp and upper neck during one night of natural sleep and one night of sleep deprivation. The patch utilized electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to measure the resistance to an electrical current applied to the tissue, thereby understanding the volume of fluid in the target region. A lower resistance score is indicative of higher glymphatic activity. The patch also monitored sleep stage using EEG, heart rate, and respiration using plethysmography, and an accelerometer for motion detection. In one of the studies, CE (contrast enhanced) MRI was used to monitor glymphatic function. Relationships between the variables were assessed using linear mixed-effects models that controlled for CE MRI contrast in brain areas other than the interstitial space, such as the blood vessels.

What did they find?

The authors found an association between resistance in the tissue of interest (indicative of glymphatic function) and contrast enhancement. They found that lower resistance predicted greater contrast enhancement, indicating that resistance, the output of the EIS device, is a good proxy for glymphatic function. When they combined resistance with variation in heart rate and EEG powerband, two other outputs of the device, they found that it explained 74.8% of the variance in the model for the awake nights, indicating that combining the device’s outputs allows it to be an even better predictor of glymphatic function. Additionally, resistance decreased during sleep, which is consistent with previous findings that glymphatic function increases during sleep. Less time in REM sleep and more time in light sleep was associated with less CE MRI contrast, indicating that in lighter sleep stages, there is less glymphatic activity.

What's the impact?

This device is the first to track glymphatic function in humans in a non-invasive and relatively time-resolved manner. This is critical to the field of neuroscience because of the glymphatic system’s association with clearing proteins involved in neurodegenerative disease, and its potential role in the control of volume transmission of neuromodulators. As a result, human glymphatic function will be able to be studied in more naturalistic environments. This device may also enable drug discovery by helping scientists understand the effect of certain drugs on glymphatic function.