The Maintenance of Adult-Born Neuron Signaling Promotes Successful Aging

Post by Amanda Engstrom

The takeaway

Memory processing via adult-born neurons is essential for successful cognitive aging. A major distinction between people who are resilient and those vulnerable to cognitive decline lies, in part, in the maintenance of a network of long-lived adult-born neurons.

What's the science?

Aging is frequently associated with cognitive decline; however, this decline varies among individuals - some individuals remain resilient while others are more vulnerable to the decline of memory functions. Memory formation relies on adult neurogenesis, the process of creating new neurons in the adult brain, but the role of long-lived adult-born neurons (ABNs) in cognitive resilience remains unclear. This week in Molecular Psychiatry, Blin and colleagues categorize aging animals as either resilient or vulnerable to cognitive decline, and examine their ABNs overall health and functionality.

How did they do it?

To determine whether ABNs generated early in adult life contribute to preserved cognition, the authors labeled ABNs at 3 months of age in rats and assessed them at 8, 12, or 18 months of age. The rats were classified as either resilient or vulnerable to cognitive aging based on their performance in a behavioral memory task. Once characterized as resilient or vulnerable, the authors assessed the ABNs from both groups. The authors first assessed the survival and levels of senescent cells (a sign of cell arrest and inability to function) in the ABN population. Additionally, they used multiple retroviral vectors to label the ABN population and assess their dendritic morphology (GFP), glutamatergic post-synaptic density (PSD95-GFP), and mitochondrial network (MitoDsRed). Finally, they used optogenetic stimulation to artificially stimulate the ABNs. Rats were injected with ChannelRhodopsin-GFP at three months and underwent learning and memory testing at 12 and 20 months of age. The ABN population was activated by light during the learning phase to test if activating them at the later timepoints would increase the rat’s performance.

What did they find?

The number of ABNs tagged at 3 months was the same in rats that were both resilient and vulnerable to cognitive aging. This was true for all three adult age groups (8, 12, and 18 months). The authors did detect senescent ABNs at all 3 ages, with an increased number of senescent cells at 18 months. However, resilient and vulnerable animals showed a similar number of senescent cells. Additionally, there was no difference in the dendritic morphology of ABNs in resilient and vulnerable rats. These data argue that the overall health of ABNs based on cell survival, entry into senescence, and gross morphology is not altered in rats vulnerable to cognitive aging.

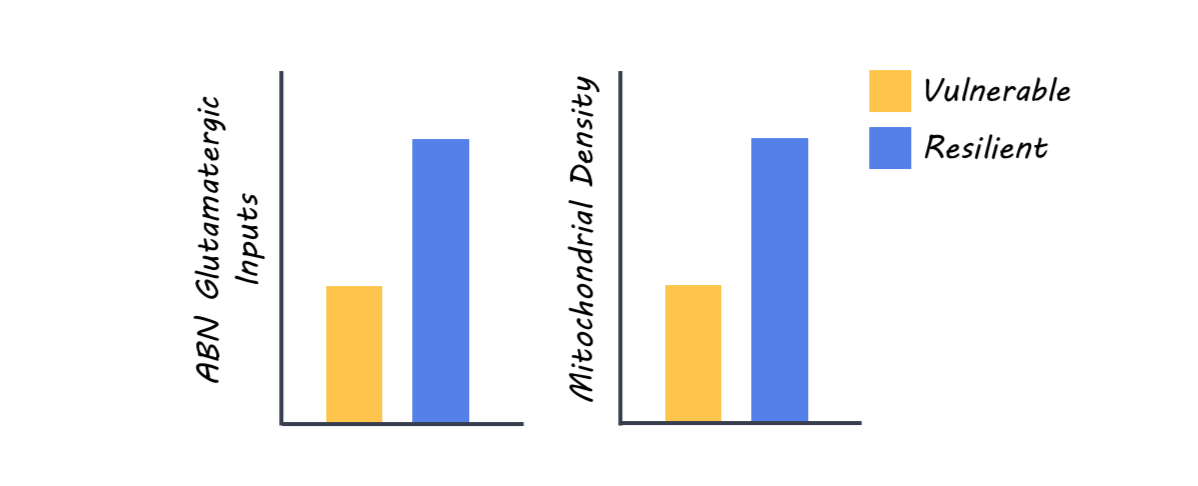

However, the authors did determine that rats vulnerable to cognitive aging progressively lost their glutamatergic inputs, indicated by a significant reduction in the labeling of postsynaptic density scaffolding protein, PSD95. The decrease of postsynaptic densities was observed at all ages in the inner molecular layer (IML) of the dendrite, but not in the middle or outer molecular layers. This suggests that the maintenance of proximal synaptic inputs (those closer to the soma or cell body) is especially important because these inputs are preserved only in resilient animals. Interestingly, the ABNs in vulnerable animals had a significant reduction of mitochondrial density, specifically in the IML at 8 months, but extended to the middle and outer layers in 18-month-old vulnerable animals. This suggests a progressive spread of mitochondrial dysfunction with aging in vulnerable animals. Optogenetic stimulation of ABNs improved the memory in all animals, and the memory of vulnerable rats improved to the level of non-stimulated resilient rats. This suggests that even when natural synaptic input is compromised in vulnerable rats, artificial stimulation can improve cognitive performance, indicating that ABNs can still function if properly engaged.

What's the impact?

This study found that long-lived ABNs play a role in cognitive aging. ABNs remain functionally viable in vulnerable animals and can transmit information when activated. Therefore, brain resilience relies, at least in part, on the preservation of the ABN integration into their neuronal network. This work highlights the potential therapeutic benefit of restoring the functionality of the ABN signaling network to improve cognitive functions in old age.