Playing Rhythm Games May Improve Stuttering

Post by Anastasia Sares

The takeaway

This proof-of-concept study tested a computer game intervention with children who stutter. Those who played a rhythm-based game had improved rhythm and speech motor skills at the end of the study, but more work is needed to establish the efficacy of this gamified intervention.

What's the science?

Developmental stuttering is a disorder of speech that is characterized by involuntary pauses, repetitions, or extensions of speech sounds. Sometimes a stutter disappears naturally as children get older, but for about 1% of the population, stuttering continues into adulthood. There is a growing body of research showing that rhythmic abilities, like tapping to a beat or hearing differences in rhythmic patterns, are linked to language abilities, like reading and speaking. Scientists are beginning to test whether rhythm training might lead to improvements in language-related disorders like dyslexia and stuttering.

This week in Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Jamey and colleagues tested whether playing a rhythm game would improve speech fluency in people who stutter.

How did they do it?

About 20 children who stutter (ages 9-12) were recruited to participate in the study. These participants were divided into two groups: the rhythm-based intervention group and the non-rhythm-based intervention group. Both groups were tested on attention/cognition, rhythm ability, speech motor ability, and stuttering frequency before the intervention began and after it was over.

The rhythm-based intervention was a game called Rhythm Workers, in which the player must tap on the screen in synchrony with the music to help construction workers build a building, with levels being added to the building based on accurate synchronization. The non-rhythm-based game was based on an open-source version of the game Frozen Bubbles, where players must shoot bubbles out of a cannon to make clusters of colored bubbles on the screen and eliminate them. The same music was played in the background of both games, and they required similar amounts of tapping on the screen. Each group played their respective games for three weeks, and were told to aim for 30 minutes to one hour each day. The use of an “active control” condition is important in this kind of work to make sure that it is the rhythmic aspect of the game, not just the gamification itself or the time and attention required, that is responsible for any gains.

What did they find?

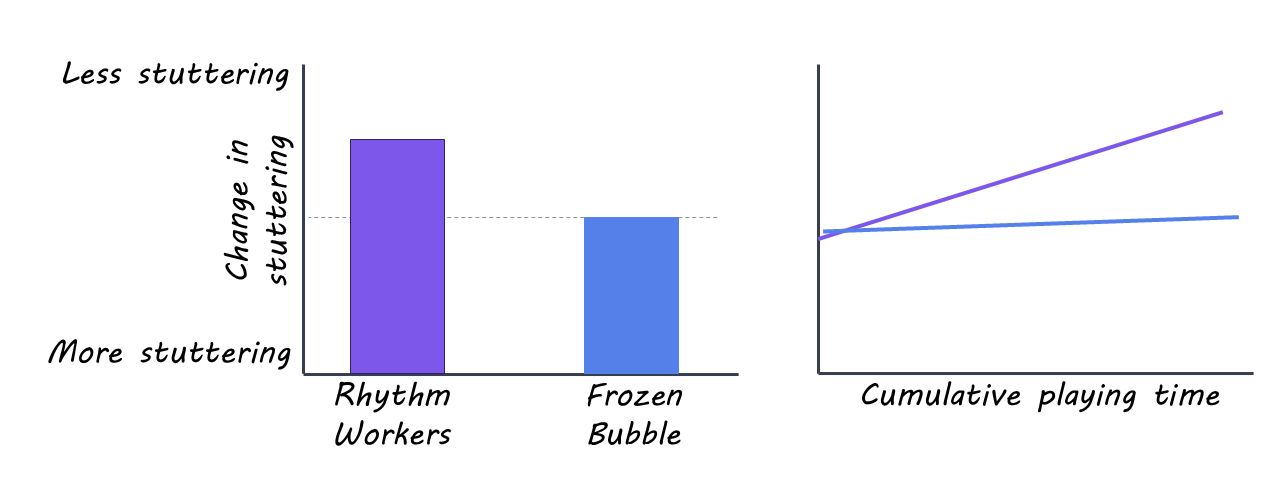

On average, both groups completed over 90% of the target amount of play time and reported enjoying the games, though there was variation between individuals in terms of their dedication and enjoyment. Both groups started out with similar scores on rhythmic behavior, attention/cognition, and speech, but the Rhythm Workers group showed some improvements in each category by the end of the intervention, while the Frozen Bubbles group did not. The more time participants spent in the Rhythm Workers game, the better their rhythm and stuttering scores were at the end of the intervention, while time spent in the Frozen Bubbles game was not related to rhythm or stuttering scores. Improvement in rhythm scores was also related to reduced stuttering.

However, the main group difference of interest—whether stuttering scores improved more with the Rhythm Workers game than the Frozen Bubbles game—did not reach significance.

What's the impact?

This study, though the sample size is small, shows promise for rhythm-based interventions in speech disorders such as stuttering. The next step will be to replicate these findings and to test whether the Rhythm Workers game (or a similar intervention) could actually lead to significant reductions in stuttering in a larger sample.