Practice Does Not Always Make Perfect: How Reward Timing Impacts Learning

Post by Annika Matthiesen

The takeaway

This study challenges the idea that we learn faster just by repeating something more often. Instead, it shows that learning depends on timing, and even when rewarded events are spaced far apart, overall learning progresses at the same pace with fewer experiences.

What's the science?

Most theories of reward learning in neuroscience argue that the learning rate is a flexible parameter with no fixed rule, and that dopamine signals whether something is better or worse than expected. However, psychology has shown that learning can improve when experiences are spread out over time, though no clear biological rule has been established.

This week in Nature Neuroscience, Burke and colleagues sought to understand how learning rates vary under different conditions.

How did they do it?

The authors trained several groups of mice to associate a sound cue with a drop of sugar water, varying the waiting period in between trials by tenfold. They measured learning by tracking anticipatory licking and monitored dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens, a key reward-related brain region, using a dopamine-sensitive virus and an implanted lens. Comparing across groups, they identified a relationship between reward spacing and learning and used mathematical models to predict both behavior and dopamine response. To test their mathematical model, they also tracked learning using partial reinforcement, giving rewards on only some trials to increase the time between rewards, keeping cue frequency the same. In addition, they examined reward omission trials, where an expected reward was withheld, to test whether dopamine signals changed when rewards were unexpectedly absent.

What did they find?

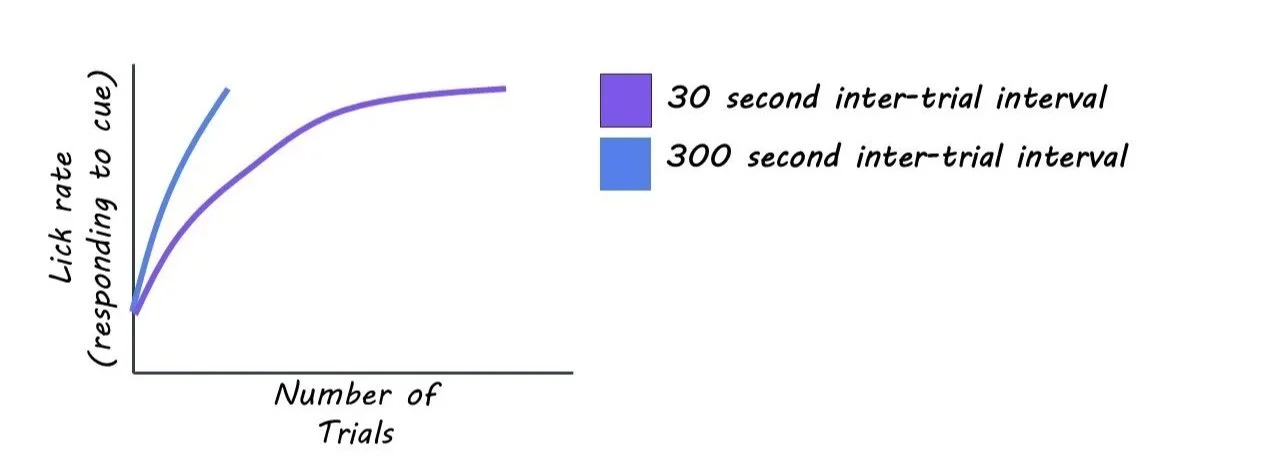

The researchers found that learning rate depends on the time between rewards, not just how often a cue and reward are paired. When rewards were spaced farther apart, animals learned more from each reward and needed fewer trials to form the association. However, the proposed mathematical learning rate prediction model did not fully hold at the most extreme condition, where rewards were separated by a very long interval. Even so, the researchers showed that the timing rule held under partial reinforcement, where rewards were delivered only some of the time, further confirming that learning scales with the interval between rewards. Additionally, dopamine signals followed the same pattern as behavior, and the emergence of dopamine responses to reward omission occurred much later than cue responses, challenging traditional reinforcement learning models. Overall, the findings reveal a fundamental timing-based rule that governs how the brain updates associations during reward learning.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to show that learning rate follows rules based on the time between cue–reward experiences, rather than simply increasing with repetition. In simpler terms, learning depends not just on practice, but on how that practice is timed. Practice alone does not make perfect, and carefully spaced timing may be key to more effective learning, reshaping how we think about education and habit formation.