How Neurons Store Memory Content and Context

Post by Amanda Engstrom

The takeaway

Recalling memories often requires linking what happened with the context in which it happened. In humans, information about content and context is largely encoded by separate neuronal populations that are coordinated over time, allowing the brain to form context-dependent memories while preserving stable independent representations.

What's the science?

The medial temporal lobe (MTL) plays a crucial role in forming and retrieving memories. In particular, the hippocampus has been implicated in encoding items-in-context memory, which involves combining what happened (the item) with the context in which it occurred (a task or environment). Rodents rely on conjunctive encoding where hippocampal representations are context dependent, however in humans, concept cells often fire independently of context. Therefore, it remains unclear how item and context memories are formed and combined at the single neuron level. This week, in Nature, Bausch and colleagues recorded activity from thousands of individual neurons during a memory and decision-making task to investigate how human MTL neurons combine information about item and context.

How did they do it?

The authors recorded activity from over 3,000 neurons in 16 neurosurgical patients implanted with depth electrodes for clinical monitoring. Individual neurons were recorded while participants performed a task-dependent picture comparison test. Each trial began with a question that defined the context (Bigger?”, “Older?”, “Last seen in real life?”, “Like better?”, or “More expensive?”). Participants were then shown pairs of pictures for which to apply the question. This task required participants to remember items (each picture) within a specific context (answering the question), while keeping the item and context information independent of each other. The electrodes recorded neuronal spiking activity across multiple regions of the MTL, including the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, parahippocampal cortex, and amygdala. Spike timing was precisely aligned to stimulus and/or task events. Using these recordings, the authors applied statistical modeling to determine whether firing was linked to the item (picture) alone, the context (task question) alone, or specific item – context interactions.

What did they find?

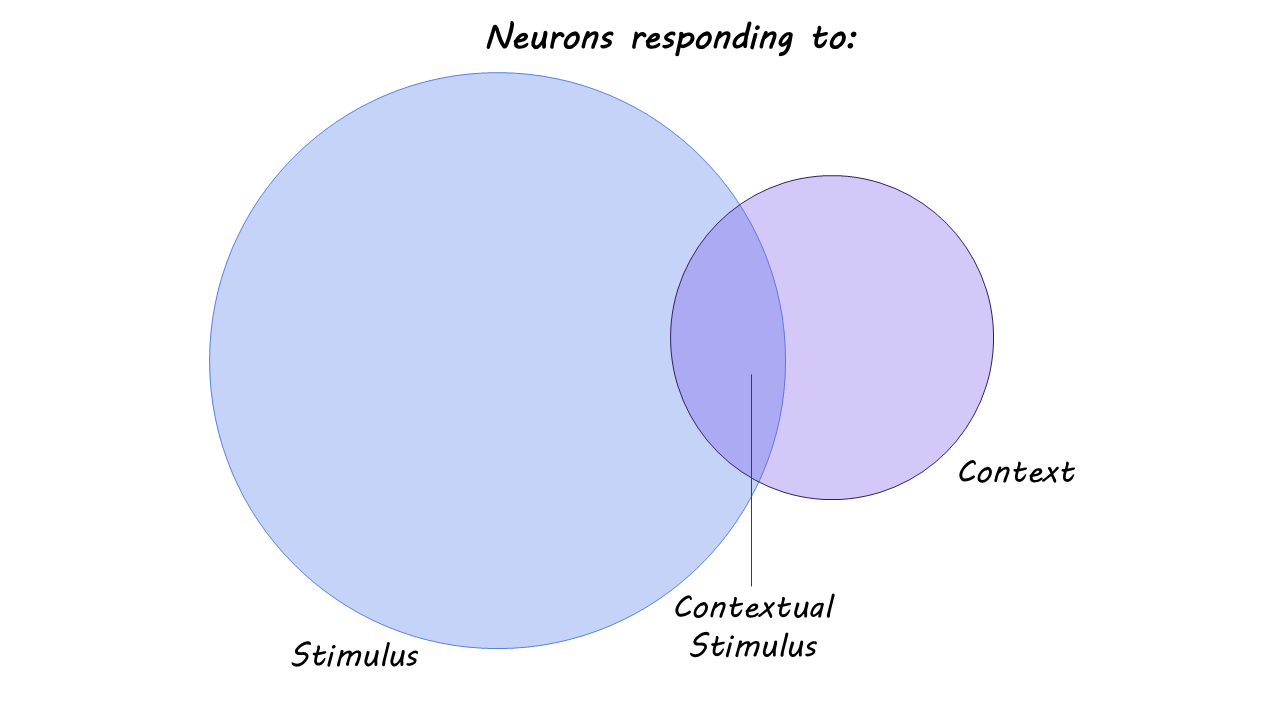

Only a small fraction of neurons fired selectively for specific item-context combinations. Instead, the majority of neurons across the MTL regions were primarily selective to stimulus (item/ picture) or context (task question). Item and context coding were largely independent, supporting a flexible and generalized memory formation pattern.

After experimental pairing and statistical modeling, the authors observed coordinated activity across MTL regions. Firing of stimulus-selective neurons in the entorhinal cortex predicted later firing of context-specific neurons in the hippocampus, suggesting that although item and context are encoded independently, they interact dynamically during memory processing. These findings support a model in which humans rely on distinct but coordinated neuronal streams to form flexible, context-dependent memories.

What's the impact?

This study found that rather than combining item and context information within single neurons, the human brain encodes them separately and then integrates them through coordinated activity between distinct neuronal groups, enabling both generalized and contextually specific recall. These findings bridge the gap between rodent models of hippocampal-dependent memory formation and human concept-cell research and provide a mechanistic explanation for how the human brain balances memory specificity with generalization, a fundamental feature of adaptive cognition.