Brain Repair Mechanisms After Stroke Differ in White and Gray Matter

Post by Anastasia Sares

The takeaway

In this study, the authors identified a gene called Lamc1, which is involved in blood vessel regeneration after a stroke, but only in the cortex (the outer layer of the gray matter) and not in the white matter, which is located deeper in the brain. This represents a potential target for medical interventions.

What's the science?

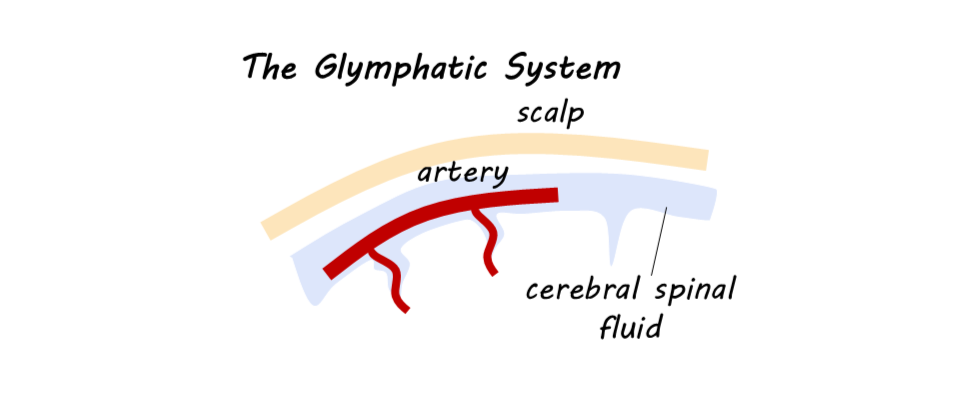

A stroke happens when a part of the brain is deprived of blood supply, either by a blockage of a blood vessel (like a heart attack, but in the brain) or by a ruptured blood vessel. When the blood supply is disrupted, neurons cannot obtain sufficient oxygen, glucose, and other essential nutrients, and they begin to die off. Stroke is one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide, but the brain does have the ability to recover some functionality after a stroke. Understanding how this brain recovery happens and what we can do to enhance it is, therefore, a high medical priority. Strokes can happen in different brain regions depending on which blood vessels are affected.

Astrocytes (named for their sometimes star-like shape) are brain cells that are crucial for stroke recovery, modifying neural connections and interacting with systems for immune function and blood flow, especially at the border between healthy and damaged brain tissue. This week in Neuron, Gleichman and colleagues examined the activity of astrocytes in different stroke locations in mice to see if there were differences in how the brain repairs itself, identifying a key process that promotes blood vessel regeneration.

How did they do it?

The authors induced strokes in the cortex of mice, which is the brain’s outer layer of gray matter (brain tissue with more neuronal cell bodies), and others were induced in white matter (containing fat-insulated axons of neurons traveling from one region of the brain to the other).

Using a multitude of techniques (viral marking, gene sequencing, and more), the authors characterized the astrocytes and their byproducts in the dissected brains. One technique, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), measures the relative quantities of different genes and how they are expressed in a piece of tissue. The authors compared gene expression following strokes in the cortex and in the white matter.

Finally, the authors measured recovery in mice affected by these different strokes. To do this, they set up a test where the mice had to manipulate small objects that had peanut butter inside the grooves. To get the peanut butter, the mice needed to pick up the objects and handle them very precisely, using regions of the brain that were affected by the stroke. Their ability to perform these precise movements was a way to track the effects of injury and recovery.

What did they find?

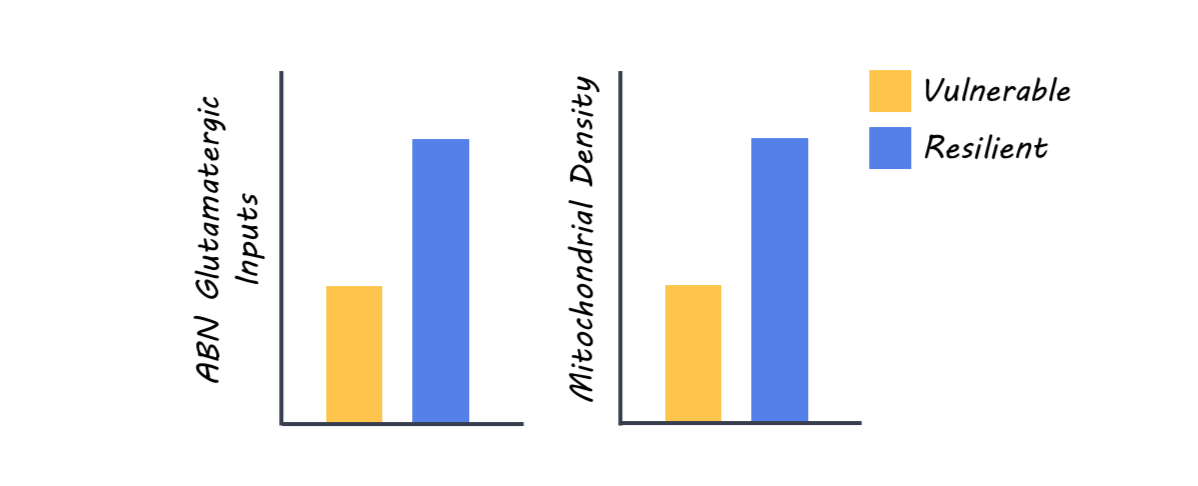

At both different types of stroke locations, astrocytes were activated at the border between damaged and healthy tissue, initiating a cascade of processes to help the brain heal. One difference that the authors noticed was that for strokes that affected the cortex, a gene called Lamc1, which is involved in blood vessel growth, was highly expressed. However, this gene was not highly expressed for strokes in the white matter.

Recovery from white matter strokes is more difficult than for cortical strokes, so the authors decided to intervene artificially and see if activating or deactivating Lamc1 would change recovery. Knocking out Lamc1 in the cortex resulted in less blood vessel regrowth, while activating Lamc1 in white matter resulted in less long-term damage, like scarring and nerve damage. The mice also seemed to maintain more consistent performance in the object manipulation task when Lamc1 was activated after a stroke, though the difference between Lamc1 and a control condition did not quite reach significance.

What's the impact?

The authors showed that artificially triggering Lamc1 activation may promote blood vessel regeneration in white matter, where it would normally be minimal. These findings can inform future clinical research into stroke treatment and recovery.