Investigating the Organization of Brain Tumor Cells Using New High-Resolution Technologies

Post by Natalia Ladyka-Wojcik

The takeaway

Using new technologies for studying the spatial architecture of gliomas reveals both local and global organization that are largely driven by hypoxia (i.e., when oxygen is not sufficiently available at the tissue level), providing critical insights for the future of cancer treatment research.

What's the science?

Glioma is a type of cancer that starts as a growth of cells in the brain or spinal cord, rapidly invading and destroying healthy surrounding tissue. Critically, gliomas are characterized by a very complex spatial architecture, making it difficult to determine the organization of their cell types and cellular states. Until recently, histopathology – or the examination of cancerous tissue under a microscope – was the dominant method for studying cell types and cellular states of gliomas, but histopathology lacks the granularity to fully capture the spatial architecture of gliomas. New technological developments have been made in spatial transcriptomics, a molecular profiling method allowing researchers to measure all gene activity in a tissue sample. When paired with advances in the study of proteins (i.e., proteomics), researchers are enabled to measure all gene activity in a tissue sample, offering new opportunities to map the complex spatial architecture of gliomas. This week in Cell, Greenwald and colleagues profiled glioma tissue samples using these new technologies to develop a framework for systematically describing the spatial organization of gliomas.

How did they do it?

The authors investigated glioma samples from patients who had undergone tumor resection across multiple hospital sights, and whose tumors ranged in their specific location in the brain as well as in their key biomarkers. These samples were frozen by liquid nitrogen for preservation and then profiled using spatial transcriptomics within one week. Broadly, the goal of spatial transcriptomics is to count the number of transcripts of a gene at distinct spatial locations in a tissue. More specifically, the authors used a commercialized transcriptomics technique, called “Visium”, to spatially profile the glioma samples at a high level of spatial granularity. This allowed the authors to investigate not only the patterns of organization across gliomas but also to determine to what degree the spatial location of gliomas affects the diversity of cellular states.

What did they find?

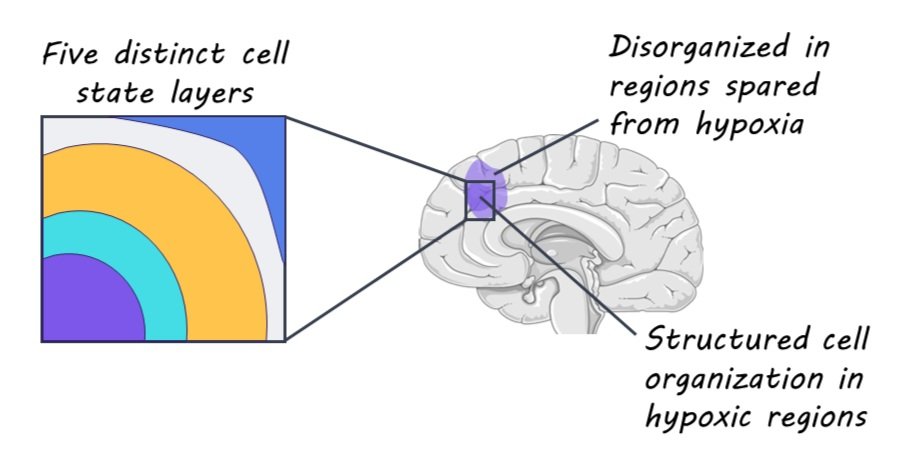

The authors identified three key modes of glioma organization, each respectively focused on 1) the local environment of glioblastoma tumors, 2) the pairing of cellular states across tumors, and 3) the global architecture of the tumors. The first key mode of glioma organization that the authors found is that cells tend to be surrounded by other cells in the same state, forming local environments that are highly homogeneous in configuration and gene expression. This finding suggests that spatial location plays an important role in the regulation of the cell state. The second key mode of glioma organization that the authors reported had to do with how pairs of states are arranged across multiple scales. That is, pairs of cellular states or gene expression patterns tend to be consistently associated with each other across different scales within the tumor tissue. Importantly, understanding these state-to-state associations across different spatial scales can help us to better understand the developmental processes of gliomas. Finally, the third key mode of glioma organization that the authors found is related to global arrangement of tissue layers. Specifically, the authors detected five distinct layers, with cell states in each layer being associated with the same layer or adjacent ones. Critically, the authors discuss that hypoxia might drive the organizational characteristics of glioma tumors such that regions spared from hypoxia are actually relatively disorganized in comparison.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to characterize both local and global organizational features of glioma tumors at a highly granular level using new advances in spatial transcriptomics and proteomics. The three key organizational modes identified in this study provide critical insights into how hypoxia drives the spatial architecture of gliomas, which in turn can support the development of targeted treatments for glioblastoma.