Could a Vaccine Prevent the Onset of Parkinson’s Disease?

Post by Rebecca Hill

The takeaway

a-Synuclein, a protein that misfolds and clumps in Parkinson’s disease, can’t be targeted normally by our immune systems. A genetically modified protein can be used to vaccinate against these malfunctioning proteins and trigger an immune response that delays symptoms of Parkinson’s.

What's the science?

Parkinson’s is caused by the misfolding and clumping of a-Synuclein (a-syn) proteins. Since we produce a-Synuclein proteins naturally, when they malfunction, our immune systems are unable to recognize and destroy them. HET-s is a protein found in a fungus that is completely unrelated to a-syn proteins in Parkinson’s. This week in Brain, Pesch and colleagues attempted to genetically modify HET-s proteins to create a vaccine against a-syn that could prevent the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

How did they do it?

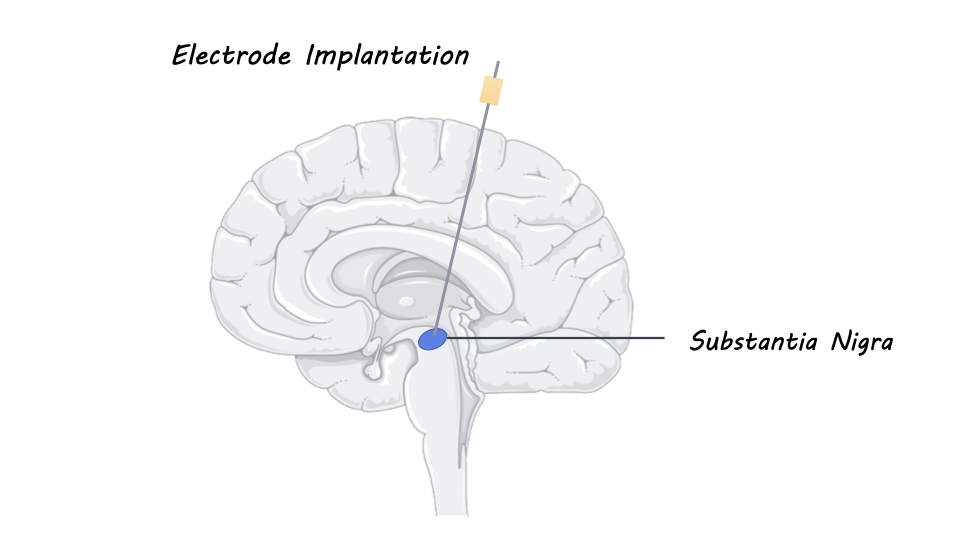

Using mutagenesis, a technique that alters DNA at specific locations, the authors changed the surface of HET-s in a way that could be identified by our immune system. This caused HET-s proteins to resemble the a-syn proteins that malfunction in Parkinson’s disease. They injected these altered HET-s proteins into mice as a vaccine to train their immune system to be able to recognize and destroy malfunctioning a-syn. They injected mice every two weeks for eight weeks and then collected blood plasma samples to analyze. The authors then injected both vaccinated and unvaccinated mice with a-syn proteins either in their brains or in their stomachs to simulate two types of Parkinson’s disease. The authors also tested mice behaviorally to examine motor strength performance.

What did they find?

Mice vaccinated with modified HET-s proteins survived 8% longer than controls when a-syn was injected into their brain and survived 22% longer than controls when a-syn was injected into their body. The authors found antibodies for the a-syn proteins in the vaccinated mice, which shows that the vaccines can lead to a better immune response to the progression of Parkinson’s disease. For both the mice that had a-syn injected into their brain or their body, vaccinated mice performed better on behavioral tests than unvaccinated mice. This means that vaccination led to better motor ability after a longer period.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to show that vaccination with engineered proteins can trigger an immune response that will delay Parkinson’s disease progression. Since Parkinson’s disease usually occurs in older adults, any delay in symptom progression could significantly impact a patient’s health outcomes. With the development of vaccines such as this, the quality of life may be significantly improved for people as they age.