The Purpose of Sleep is to Restore our Brain to an Optimized State Called Criticality

Post by Trisha Vaidyanathan

The takeaway

The waking experience pushes the cerebral cortex away from “criticality”, a state of neural activity that is optimized for computation and cognition. The function of sleep is to restore the brain to criticality.

What's the science?

We spend about one third of our lives sleeping, but the purpose of sleep is debated. Broadly, we understand that sleep is “restorative”, but it is unclear how sleep contributes to brain computation and information processing. This week in Nature Neuroscience, Xu and colleagues provide new evidence to support a theory that one of the primary functions of sleep is to restore the brain to an optimized state called “criticality.” Criticality is a concept borrowed from physics that describes when a system of individual parts will be most effective at responding to an input. It makes sense that our brain should operate at criticality so that it can quickly and effectively process new information – for example, if our brain receives new visual input caused by a tiger appearing, it should quickly and effectively transmit that information to brain regions that will drive us to run away.

How did they do it?

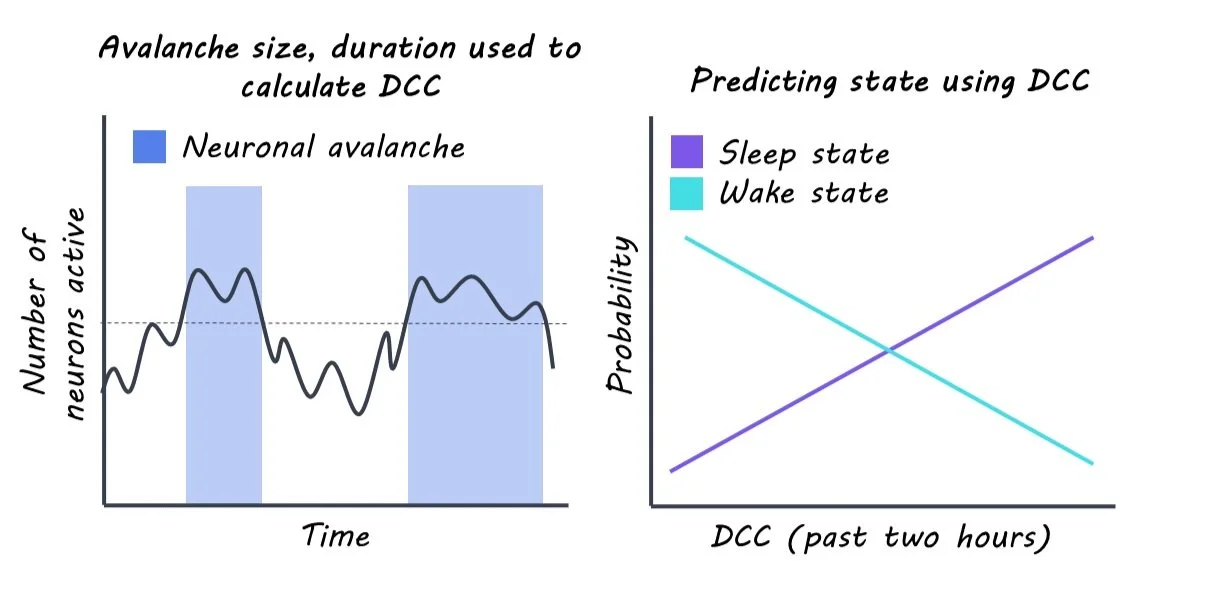

To measure how close the brain is to criticality, the authors performed continuous extracellular recordings of individual neurons in the visual cortex of rats. Criticality is characterized by neuronal avalanches, which are cascades of bursts of neuronal activity. This allowed them to create a score that measured how close the cortex was to criticality at any given time called the “deviation from criticality coefficient”, or DCC. The higher the DCC score, the further the brain is from criticality. Because rats constantly switch between wake and sleep throughout the day, the authors could assess how the DCC score fluctuated with wake and sleep.

Using the DCC score, the authors tested their theory that wakefulness pushes the brain away from criticality and sleep restores criticality. First, the authors asked how the DCC score changed during sleep and wake. Next, they asked whether the DCC score was predictive of future sleep/wake behavior and if the DCC score could be predicted by previous sleep/wake behavior. Lastly, they asked if the DCC score would change if the rats were forced to stay awake for longer periods of time.

What did they find?

First, the authors found that more time in a waking state correlated with higher deviation from criticality (i.e., higher DCC scores) and more time in sleep correlated with lower DCC scores, consistent with their theory. Interestingly, the effect was greater when the rats spent more time moving during wake and the effect was absent when the rats were awake but in the dark. This suggested that not all wake experiences are the same and that more stimulation during a waking state can result in a greater deviation from criticality.

The authors found that future sleep/wake behavior could be predicted using the DCC score. The DCC score was more predictive than other known regulators of sleep, like the time of day or prior amount of sleep. Further, the authors could predict the DCC score by using the sleep/wake behavior from the previous two hours, in support of the theory that sleep and wake drive changes in criticality.

When rats stayed awake for periods of 90 minutes, slightly longer than normal, the DCC score increased as predicted by their theory that wakefulness pushes the brain away from criticality. When the rats were allowed to sleep again, the DCC score went back down, demonstrating the restorative effect of sleep on criticality.

What's the impact?

This study addresses a big mystery in neuroscience: why do we sleep? The authors provide strong evidence that one of the primary functions of sleep at a systems level is to restore the brain to an optimal state described by the theory of criticality.