Hippocampal Activity Can Distinguish Traumatic Memories from Sad Memories

Post by Shireen Parimoo

The takeaway

In post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic memories are a type of autobiographical memory that are similar to memories of sad, but non-traumatic life events. However, patterns of activation in the hippocampus (a key brain region involved in autobiographical memory) differ for traumatic and sad memories, indicating that traumatic memories symbolize a distinct cognitive state.

What's the science?

Post-traumatic stress disorder is characterized by exposure to a traumatic event that individuals subsequently re-experience through intrusive dreams and flashbacks. Individuals with PTSD show altered functioning of the hippocampus, posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and amygdala, which are brain regions involved in memory reconstruction, re-experiencing of an event, and emotional processing, respectively. However, the same negative event (like the loss of a loved one for example) can be traumatic for one individual while being perceived as sad, but non-traumatic by another. In both cases, those same brain regions are likely to be activated, raising the question of whether traumatic and sad autobiographical memories only differ in their intensity or whether they represent distinct cognitive states. To investigate whether the neural representations underlying traumatic and sad memories are shared or distinct, a study in Nature Neuroscience by Perl and colleagues used fMRI to decode brain activity in different regions as individuals with PTSD listened to audio narratives of traumatic and sad memories from their lives.

How did they do it?

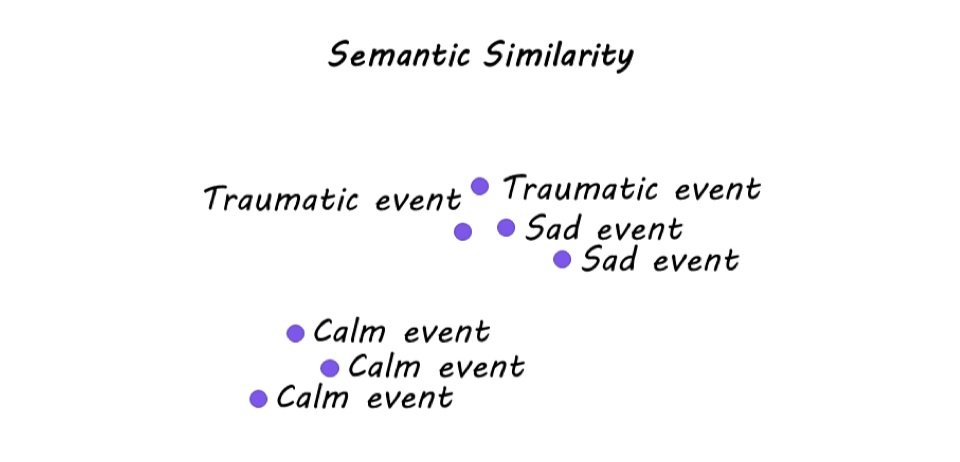

Twenty-eight adults diagnosed with PTSD were recruited for this study. During their initial visit, they were asked to recount (i) the traumatic event associated with their diagnosis (‘Traumatic’), (ii) a sad, non-traumatizing event (‘Sad’), and (iii) a positive and relaxing event (‘Calm’) from their life in as much detail as possible. The authors used these events to create audio narratives that the participants later listened to while undergoing fMRI scanning. Semantic analysis was performed to obtain a semantic representation of the content - the meaning and key ideas present within the narratives (e.g., losing a job). They used a dimensionality reduction method called t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding to reduce the number of features in a dataset while retaining meaningful information. This then allowed them to identify and match the traumatic and sad memories on the types of semantic content, enabling them to use the sad memories as a comparison against the traumatic memories for brain activity.

The authors then examined neural activation in the hippocampus, PCC, and amygdala for each narrative category and created a neural similarity matrix. Similarly, they compared the semantic similarity within and across the narratives in each category. Next, they used inter-subject representational similarity analysis (IS-RSA) to compare brain activity to the semantic similarity of narratives across participants. This approach allowed them to see whether higher semantic similarity of the different narrative categories was associated with greater neural similarity across participants. To determine whether the severity of PTSD symptoms was associated with the neural representation of traumatic memories, they divided the participants into ‘high’ and ‘low’ symptom groups and performed the IS-RSA again. Lastly, the authors used linear discriminant analysis (a classification method) to investigate whether brain activity while listening to the narrative could be used to decode the corresponding narrative category.

What did they find?

Semantic analysis revealed that Calm narratives were most similar to each other and least similar to the Sad and Traumatic narratives. On the other hand, while Traumatic narratives were highly idiosyncratic in their semantic content, they showed semantic overlap with Sad memories. In the brain, hippocampal representation of Sad and Traumatic memories varied across individuals. Specifically, greater semantic similarity of Sad memories was associated with greater similarity in hippocampal activation across participants. However, this was not the case for Traumatic memories, indicating that the hippocampus only tracks the semantic content of Sad memories. Moreover, hippocampal activity could be used to distinguish between Sad and Traumatic memories, whereas activity in the amygdala was not sensitive to the narrative category.

When neural activity was examined as a function of symptom severity, there was no difference in hippocampal or amygdala activity for Sad or Traumatic memories. In contrast, greater symptom severity was related to stronger neural representations of Traumatic – and, to a lesser extent, Sad – memories in the PCC. Together, these results demonstrate that the hippocampus differentially represents the semantic content of Sad and Traumatic autobiographical memories while the neural representations in the PCC are more sensitive to the severity of PTSD symptoms within individuals.

What's the impact?

The authors used an innovative approach to examine brain activity while participants listened to narratives of events from their own lives. This study is the first to show that the re-experiencing of traumatic memories represents a distinct cognitive state from remembering sad or negative autobiographical memories, which has important implications for informing treatments for individuals with PTSD.