Predicting How Adversity Changes the Brain

Post by Christopher Chen

The takeaway

Environmental stressors alter our brains. These alterations endure over time, and individual deviations from shared neural patterns associated with adversity hold the potential to predict future psychopathology, like anxiety.

What's the science?

Brain imaging technologies like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have enabled researchers to gather evidence that adversity, particularly during early childhood and adolescence, can lead to abnormal brain development. This may play a significant role in later psychological disorders in adulthood. For instance, brain imaging studies have demonstrated that factors like childhood trauma and poverty can impact the volume of crucial brain regions such as the hippocampus and amygdala - brain regions that are integral to emotion and cognitive function.

Specific types of adversity are thought to uniquely affect particular brain regions, however, it’s still unclear how we can predict outcomes from different types of adversity for unique individuals. Recently in Nature Neuroscience, Holz and colleagues leveraged machine learning and brain imaging data to uncover how distinct types of adversity influence the brain, how this varies across individuals, and how we can predict an individual's likelihood of developing anxiety.

How did they do it?

The researchers conducted a comparative analysis of brain images from 169 at-risk individuals and healthy controls who were part of the Mannheim Study of Children at Risk (MARS), a well-known longitudinal investigation tracking these individuals from birth into adulthood. A replication sample was derived from another imaging study known as the IMAGEN study and shared similar demographic characteristics with the MARS group. The researchers used machine learning to develop a normative model of brain development based on adversity in the MARS group. The same model was employed to generate normative brain images for the same at-risk individuals eight years later and for the replication sample from the IMAGEN study.

The researchers then engaged in a detailed comparison of essential components within and between these three normative brain models. This included employing a measurement called the dice coefficient to assess the extent of overlap between the neural patterns associated with different types of adversity. Additionally, they harnessed individual-specific z-scores (i.e. how many standard deviations a value is from the mean) to gauge the deviation between an individual’s brain images and the normative brain model. By using linear mixed models, they could gauge how these neural deviations at the individual level predicted the manifestation of anxiety.

What did they find?

In terms of the brain images from at-risk individuals, the researchers observed a consistent neural signature across subjects, implying that heightened adversity impacts similar brain regions. Remarkably, while brain regions like the hippocampus and amygdala, known to be affected by adversity, exhibited changes in volume, the researchers also noted persistent volume changes in non-limbic system regions like the occipital gyrus and thalamus. They further uncovered that this neural signature remained stable over time.

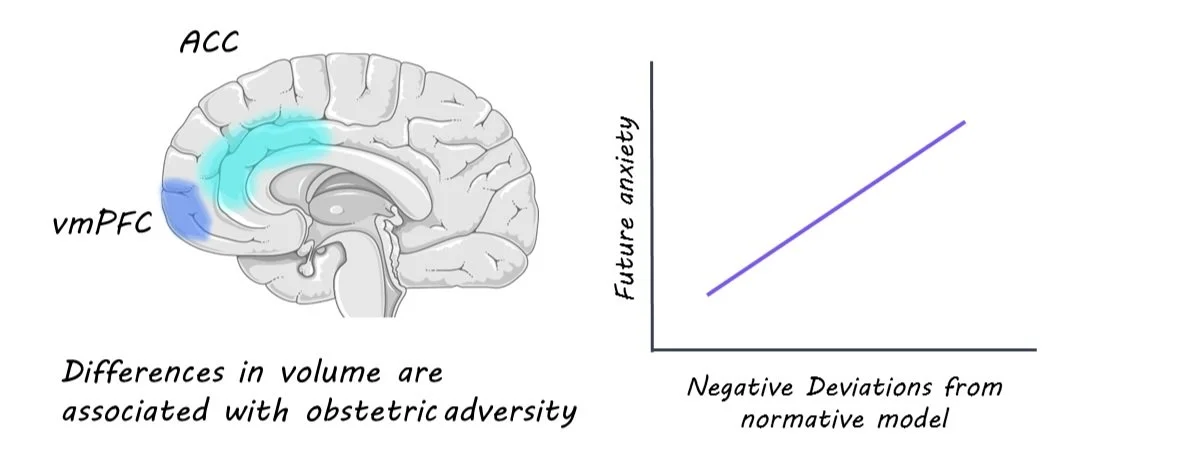

Using dice coefficients, the researchers showcased the links between specific types of adversity and corresponding changes in distinct brain regions. Adversities such as prenatal maternal smoking and obstetric challenges demonstrated lower dice coefficients, signifying their unique impact on specific brain areas. For instance, prenatal maternal smoking was closely tied to volume expansions in the hippocampus and volume contractions (i.e. reductions) in the postcentral and occipital gyrus. Meanwhile, obstetric adversity correlated with volume expansions in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and volume contractions in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).

Perhaps the most intriguing revelation was the predictive capacity of the normative model. The researchers discovered that significant negative deviations (indicating volume reduction) in an individual's brain were associated with a higher predisposition to future anxiety.

What's the impact?

These findings underscore the positive correlation between adversity-induced brain changes and the likelihood of anxiety. Moreover, the research suggests that the effects of adversity on the brain could be more profound and enduring than previously believed. Although the study's scope was limited to adults and a relatively small cohort, its specificity holds promise for aiding researchers and healthcare professionals in developing more targeted and effective strategies to help individuals navigate the repercussions of adversity in their lives.