A New Bird Model for Studying Vocal Production

Post by Rebecca Hill

The takeaway

There has been little focus on female birdsong until recently, leaving many questions unanswered about how the female brain is involved in singing. Male and female red-cheeked cordon bleus that sing at the same rate have similar hormone and brain composition.

What's the science?

Bird song learning can be used as a model for human vocal learning, but up until recently the field has focused on studying species where only male birds sing. Studying bird species where females sing will give us a more complete understanding of how hormones and the brain control vocal production. This week in Journal of Comparative Physiology, Rose and colleagues studied the red-cheeked cordon bleu, a bird species in which both males and females sing, by recording their song behavior, measuring their hormone levels, and analyzing the brain regions involved with vocal production.

How did they do it?

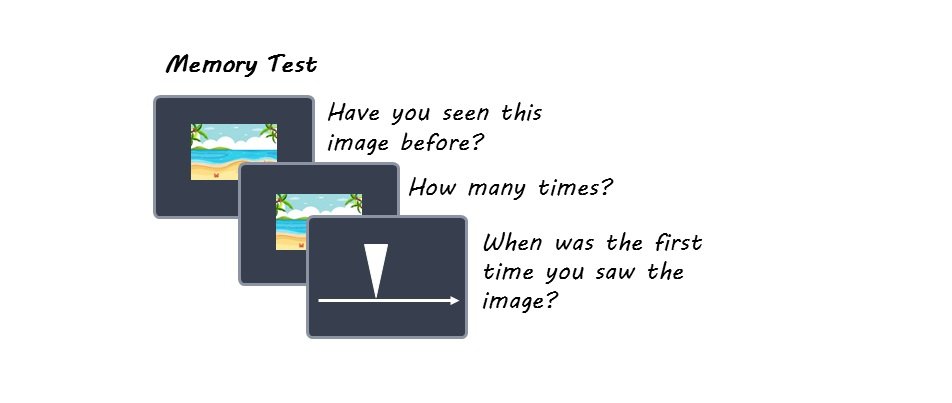

The authors first studied the song behavior of 20 birds (10 males and 10 females) by putting them in sound recording chambers, which cut down on background noise. They recorded each bird for one hour, eight times over a month, and found the recording with the most songs sung. They recorded the birds’ song rate by dividing 20 by the number of minutes birds took to sing 20 songs. They also counted the number of songs the birds sang in the first 30 minutes of singing on the day of tissue collection.

The authors also studied the hormones and brain regions involved in singing by collecting blood and brain tissue. They studied the sex hormones testosterone and progesterone, which are known to be involved in singing rate, by measuring the concentration of them in the blood. They studied three brain regions: 1) Area X of the striatum, which is involved in song learning, 2) RA (the robust nucleus of the arcopallium), which is involved with song production, and 3) HVC (the acronym is the proper name), which connects to both learning and song production pathway and is the central vocal production area in the brain. They measured the volume of these brain regions and the ZENK protein expression, which shows the level of activity in the brain in certain areas.

What did they find?

Male and female birds both sang at high song rates, and their songs were similar in total length and structure. Both testosterone and progesterone hormone blood levels were similar between males and females. This suggests both sexes have similar hormonal mechanisms that drive song behavior. Area X and HVC were larger in males than females, but RA volume was similar between the two sexes. This suggests that song production pathways are similar, but song learning pathways are different between the sexes. Birds that sang had more ZENK expression than birds that were not singing in both sexes, which suggests that there were similar levels of brain activity involved with producing singing.

What's the impact?

This study found that red-cheeked cordon bleus have very few behavioral, hormonal, and brain sex differences compared to other species often studied in the lab. This means they could be a good model species to study mechanisms controlling vocal behavior as a model for human vocal production. Understanding how the brain is involved with speech can help us to diagnose and treat speech and communication disorders.