How Do Sleep Oscillations Promote Long-Term Memory Storage?

Post by Trisha Vaidyanathan

The takeaway

In 1924, a study found that participants remembered a list of nonsense syllables better if they slept – rather than stayed awake – after learning. Since then, many studies have demonstrated how sleep promotes memory. A prevailing theory is that long-term memory is formed during sleep where short-term memories in the hippocampus are transferred to the cortex for long-term storage. This memory storage process is thought to rely on the precise timing of three distinct neural oscillations in the brain.

What is long-term memory storage?

Memory consolidation, also known as long-term memory storage, is the process by which newly formed “short-term” memories are transformed into long-term, stable memories. Short-term memories are largely encoded in the hippocampus, where the neural representation of a memory is prone to fading. However, these hippocampal representations can be transferred to the cortex for long-term storage during memory consolidation, where there is unlimited capacity for new memories throughout our lifetime.

Memory consolidation starts with “hippocampal replay”

A new memory is composed of several features, including sound, vision, taste, and even emotion. The hippocampus integrates all these features into one unique neural representation or a precise pattern of neuronal activity. As such, new memories are initially completely dependent on the hippocampus. During sleep, the hippocampal neuronal representation of a memory continually “replays” and the sequence of neuronal activity repeats over and over again. Hippocampal replay events mostly occur during a specific stage of sleep called non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and represent the starting point by which these memories are transferred to the cortex for long-term storage.

Three key oscillations coordinate to promote long-term memory storage

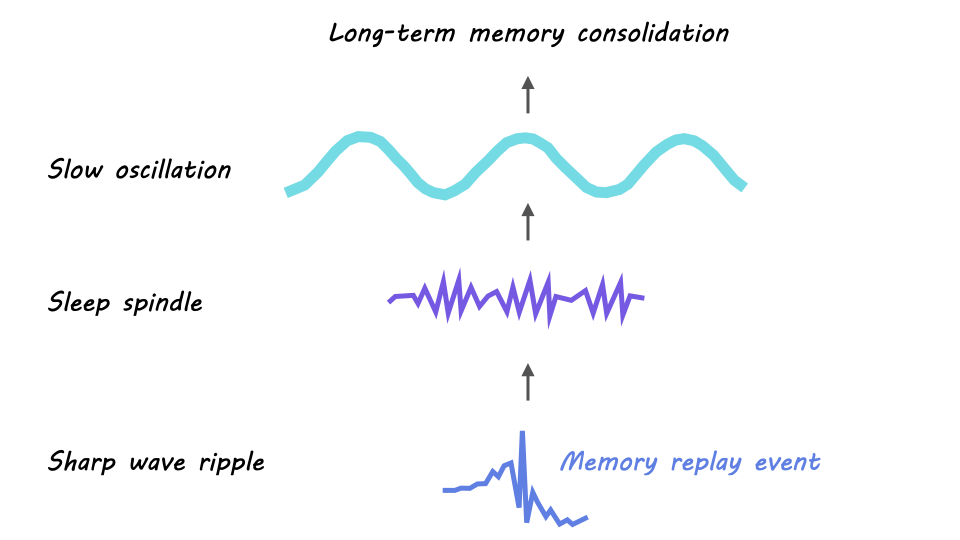

How exactly is information transferred from the hippocampus to the cortex during sleep? The prevailing theory is that this transfer occurs because of the precise timing of 3 different types of neuronal oscillations. A neuronal oscillation is generated when a population of neurons continually alternates between synchronous activity and synchronous silence. The precise timing of these oscillations drives communication between brain areas because of spike timing dependent plasticity, or the phenomenon in which two co-active neurons will strengthen their connection.

The first key oscillation is the sharp wave ripple, a high-frequency oscillation (150-250Hz) generated in the hippocampus during NREM sleep. The sharp wave ripple is critical for memory consolidation since hippocampal replay occurs during the burst of activity that is generated in the active phase of a sharp wave ripple.

The second key oscillation is the sleep spindle. Sleep spindles are slower oscillations (12-15Hz) that originate in the thalamus during NREM sleep and spread to the cortex and hippocampus. In the hippocampus, sharp wave ripples tend to nest into the troughs – or the active phases – of sleep spindles. This spindle-ripple coupling forms the first bridge by which neuronal activity is transferred outside of the hippocampus.

The last key oscillation is the slow oscillation, a low-frequency oscillation (<1Hz), generated within the cortex in NREM sleep. The active phase of the slow oscillation also called the UP state, can drive the thalamus to generate sleep spindles (which, as mentioned above, are associated with hippocampal sharp wave ripples). This slow-oscillation-spindle-ripple coupling is thought to be the foundation of memory consolidation from the hippocampus to cortex.

In sum, a prevailing model of memory consolidation is that the cortex opens a window for memory consolidation during sleep when a cortical slow oscillation drives the thalamus to generate a sleep spindle, which in turn synchronizes a hippocampal sharp wave ripple containing a replay event. The resulting synchronous activity – the replay event nested in the sharp wave ripple, nested in the sleep spindle, nested in the slow oscillation – across the cortex, thalamus, and hippocampus is believed to drive memory consolidation through neuronal spike timing dependent plasticity.

How does this affect our memories?

The theory that long-term memory storage relies on the transfer of memory from the hippocampus to the cortex suggests that our memories could be susceptible to alteration during this process. In fact, there is evidence that suggests the cortex can integrate new memories into pre-existing stored information. This may underlie our ability to extract general principles from a series of individual memories. Additionally, other factors like emotional state may bias how memories are stored. However, further research is needed to better understand these transformations of memory and how they occur.

References +

Goode, T. D., Tanaka, K. Z., Sahay, A. & McHugh, T. J. An integrated index: engrams, place cells, and hippocampal memory. Neuron 107, 805–820 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.07.011

Guskjolen, A., Cembrowski, M. S. Engram neurons: Encoding, consolidation, retrieval, and forgetting of memory. Mol. Psychiatry (2023) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02137-5

Jenkins, J. G., Dallenbach, K. M. Obliviscence During Sleep and Waking. The American Journal of Psychology, 35, 605–612 (1924). https://doi.org/10.2307/1414040

Joo, H.R., Frank, L.M. The hippocampal sharp wave–ripple in memory retrieval for immediate use and consolidation. Nat Rev Neurosci 19, 744–757 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-018-0077-1

Klinzing, J.G., Niethard, N. & Born, J. Mechanisms of systems memory consolidation during sleep. Nat Neurosci 22, 1598–1610 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0467-3

Skaggs, W. E., McNaughton, B. L. Replay of neuronal firing sequences in rat hippocampus during sleep following spatial experience. Science 271, 1870–1873 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.271.5257.1870