How Does Episodic-Like Memory Formation Develop?

Post by Baldomero B. Ramirez Cantu

The takeaway

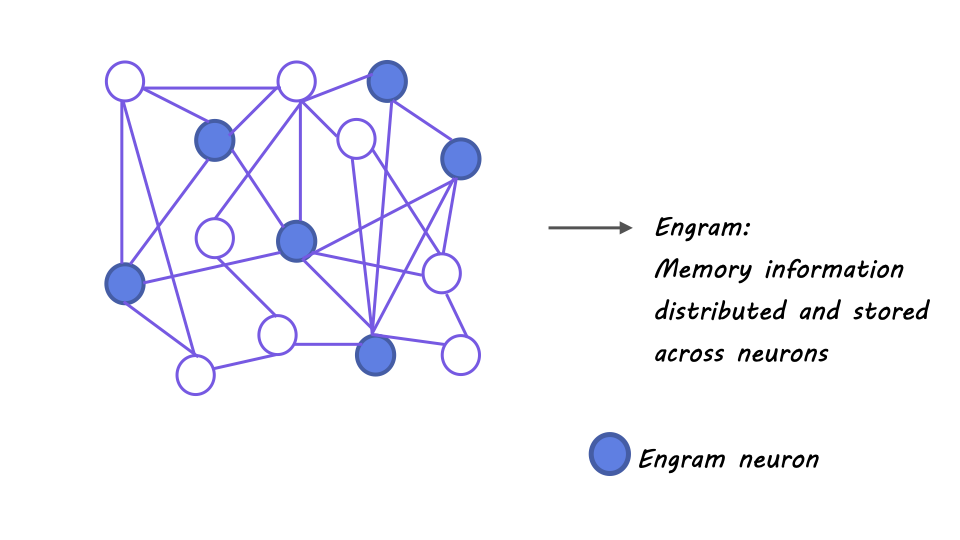

The development of the hippocampus from birth involves multiple stages of functional maturation, which are responsible for increases in the precision of episodic and episodic-like memory as we age. Engram sparsity (i.e. how scattered or distributed it is across brain regions) and the maturation of a specific subset of inhibitory interneurons are key features of this development.

What's the science?

Episodic memory refers to an individual's personal recollection of experiences, events, and situations, which is not innate but rather developed through brain maturation. However, the specific neurobiological mechanisms underlying the transition from gist-like memories to more precise, detailed memories remain unclear. This week in Science, Ramsaran and colleagues provide insights into the underlying neurobiological basis of the development of episodic-like memory.

How did they do it?

The authors used a variety of techniques in order to investigate the development of hippocampal engrams (i.e. physical memory traces in the brain) and episodic-like memory in mice. They primarily relied on behavioral assays of memory, optogenetic and chemogenetic manipulations, and immediate early gene expression markers. First, the authors trained mice in contextual fear conditioning tasks at different ages in order to test their ability to recall a particular context as a function of their age. They optogenetically silenced the activity of the CA1 region of the hippocampus while the mice performed this task in order to first check whether the task was hippocampus dependent in juvenile and adult mice.

Next, they manipulated CA1 activity by expressing either excitatory or inhibitory designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs) and observed the effect that these manipulations had on engram size and sparsity. The authors then tested the role of CA1 neurons in memory recall in mice aged 20, 24, and 60 days by expressing both excitatory and inhibitory opsins in the same subset of neurons. They expressed an inhibitory DREADD into parvalbumin expressing (PV) inhibitory interneurons to test the role of these neurons in engram density and sparsity. Furthermore, the authors perturbed the expression of perineuronal nets (PNNs) — crucial for the appropriate development and function of parvalbumin inhibitory interneurons — using a viral vector approach.

What did they find?

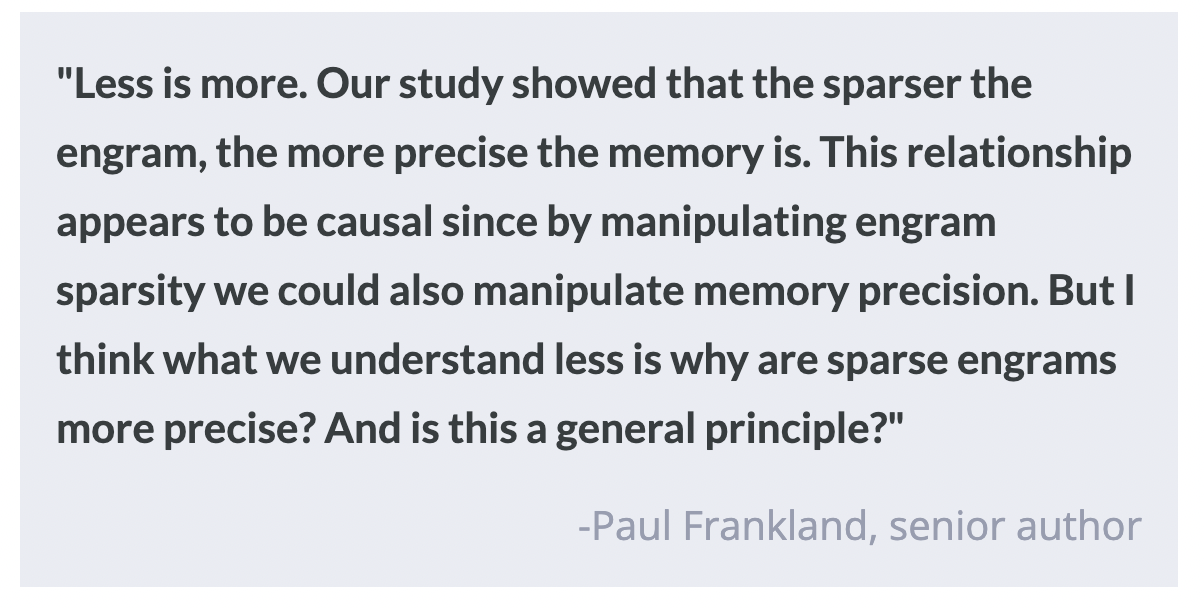

Inhibiting a subset of CA1 neurons with inhibitory DREADDs prior to memory acquisition decreased engram size and led juvenile mice to display adult-like memory precision. Conversely, activating these neurons with excitatory DREADDs increased engram size and caused adult mice to exhibit juvenile-like memory. Silencing of CA1 neurons using the bidirectional optogenetic strategy described above hindered fear recall in 24 and 60 day old mice, but not in 20 day old mice. This suggests that information is stored in a much broader subset of neurons in the 20 day old mice and therefore that the sparser the engram is, the more precise the memory is. Therefore inhibiting only a subset of these neurons is not sufficient to fully impair memory recall. Chemogenetic inhibition of PV neurons during learning caused the expression of juvenile-like memory allocation and imprecision. These findings support the hypothesis that immature PV neuron function may underlie juvenile-like memory phenotypes. Perturbing and destabilizing CA1 PNN resulted in imprecision of contextual memory, while accelerating the maturation of CA1 PNN led to adult-like engram formation and precise contextual memory acquisition.

What's the impact?

This study expands our understanding of how memory develops and is stored in the brain and can inform the development of strategies for enhancing memory function and treating memory-related disorders. In addition, this research provides important insights into the complex processes of neural development and maturation.