How the Brain Creates False Memories Based on Misinformation

Post by Kulpreet Cheema

The takeaway

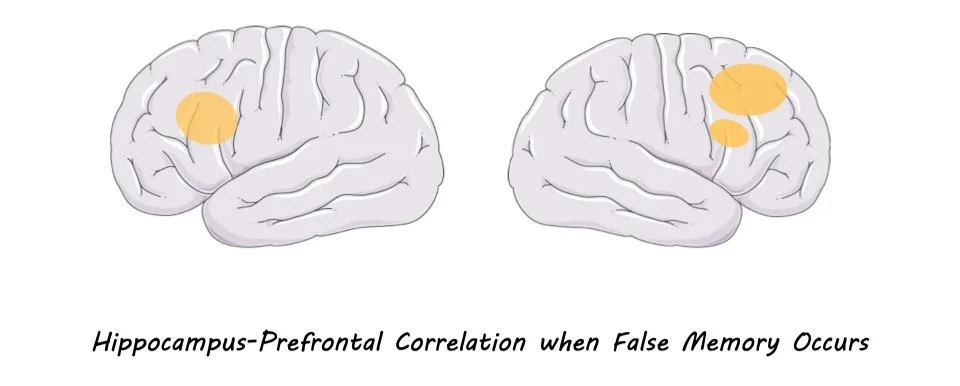

Hippocampal activity and connectivity with prefrontal and parietal cortices in the brain are responsible for creating misinformation-induced false memories.

What's the science?

The misinformation effect is when a memory of an event changes after exposure to misleading information. False memories can occur as a result of the misinformation effect. The classic three-stage misinformation paradigm involves someone witnessing an event, exposure to the misinformation, and finally performing a memory test about the original event. The hippocampus is a brain structure involved in these three stages of memory, however, how hippocampal representations change across these stages is not well known. This week in Nature Communications, Shao and colleagues investigated the role of the hippocampal-cortical network involved in creating misinformation-induced false memories.

How did they do it?

The authors performed behavioral and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies to investigate the misinformation effect. In study one, 122 participants were randomly assigned to the misinformation, neutral or consistent group. The misinformation group had the highest number of false memories, confirming that the misinformation paradigm did lead to increased false memories. In study two, another 57 participants completed a memory test in an fMRI scanner. The study had three stages: during the original-event stage, participants were shown photos of eight events and later heard narratives about the photos (during the post-event phase). Nineteen hours after the post-event stage, the memory of the original event was tested in a memory test. In the misinformation condition, the descriptions of the critical elements of the original photos given in the narratives were inaccurate.

The activity of hippocampal and prefrontal brain regions during the three stages was analyzed to investigate their involvement in true and false memories. This was followed by a whole-brain ‘searchlight’ analysis to see whether other brain regions were involved in false memory and the misinformation effect.

What did they find?

The hippocampal activity pattern during the original-event and post-event stages were similar, suggesting the original information was reactivated in the hippocampus during the misinformation (i.e., post-event) stage. Prefrontal brain activity was more positively correlated with hippocampus reactivation of post-event information during false memory than original-event information representation. This means the prefrontal cortex works with the hippocampus to monitor memory traces and resolves conflict when false memories occur. In addition to the hippocampus, the participant-specific representations stored in the lateral parietal cortex predicted true memory. On the other hand, misinformation during the false memory was supported by the hippocampus and medial-parietal cortex activity. This suggests that lateral and medial parietal cortices were distinctly connected to the hippocampus to carry original-event and post-event information to create true and false memories, respectively.

What's the impact?

This study shows that dynamic changes in the activity and connectivity of the hippocampus, prefrontal and parietal cortices create the misinformation effect. The representations of original information in the hippocampus become weak when a memory is retrieved, and the misinformed memory representations compete with these original representations. The results also support the multiple-trace memory theory and confirm human memory's fragile and reconstructive nature.