This is Your Brain on Burnout

Post by Elisa Guma

What is burnout?

Chronic physical, emotional, or mental exhaustion, decreased motivation, lowered performance, and negative attitudes towards oneself and others are all symptoms of “burnout”. This syndrome is familiar to many professionals in high-stress, demanding jobs. Burnout is usually caused by work that demands continuous, long-term cognitive, emotional, or physical efforts in concert with a perceived lack of control in the face of a demanding workload, as well as a lack of adequate social support or poor self-care (Vladut et al., 2010). While work-related stress is often the cause, burnout can also occur in other areas of life, such as parenting, caretaking, or romantic relationships.

How does burnout affect the neuroendocrine system?

Chronic stress conditions like burnout can cause dysregulation of the neuroendocrine system through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Oosterholt et al., 2014). When faced with an acute stressor (ex: seeing a snake in the grass), the body responds by increasing cortisol concentrations in the body, triggering the fight or flight response. Once the threat has passed cortisol levels fall and return to baseline. However, in chronic stress conditions like burnout, the body is unable to bring cortisol levels back to baseline, which wreaks havoc on our body’s neuroendocrine system. Prolonged stress and chronically elevated cortisol levels can lead to abnormally low baseline cortisol levels, (Oosterholt et al., 2014), increasing inflammation in the body and the risk for heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and vulnerability to illness (Toker et al., 2012). It can also increase susceptibility to anxiety, depression, or misuse of drugs and alcohol (Ogbonnaya UC et al., 2022).

How does burnout affect brain structure and function?

Chronic stress, a key underlying feature of burnout, has been associated with increasing risk for both mental health conditions and physical illness, as well as changes in brain structure and function (Miranda et al., 2022). Neuroimaging studies of individuals experiencing chronic occupational stress have shown alterations to limbic and paralimbic networks that are commonly observed in other chronic stress conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder or childhood maltreatment (Savic 2015, Savic et al., 2018; Blix et al., 2013). These include cortical thinning of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), implicated in higher-order executive function and decision-making, as well as reduced functional connectivity of the PFC to other brain regions. Importantly, some studies demonstrate that cortical thinning is more pronounced in females than males, highlighting potential sex-specific vulnerabilities (Savic 2015, Savic et al., 2018; Blix et al., 2013). Alterations to limbic structures have also been reported, including reduced anterior cingulate cortex volume, and reduced functional connectivity between that region and the amygdala (Golkar et al. 2014). Additional studies demonstrate that females under chronic stress have enlarged amygdala volume while males have enlarged caudate volume (Savic et al., 2018). Importantly, the magnitude of these changes has been associated with the degree of perceived stress, pointing to some potential dose-response relationship.

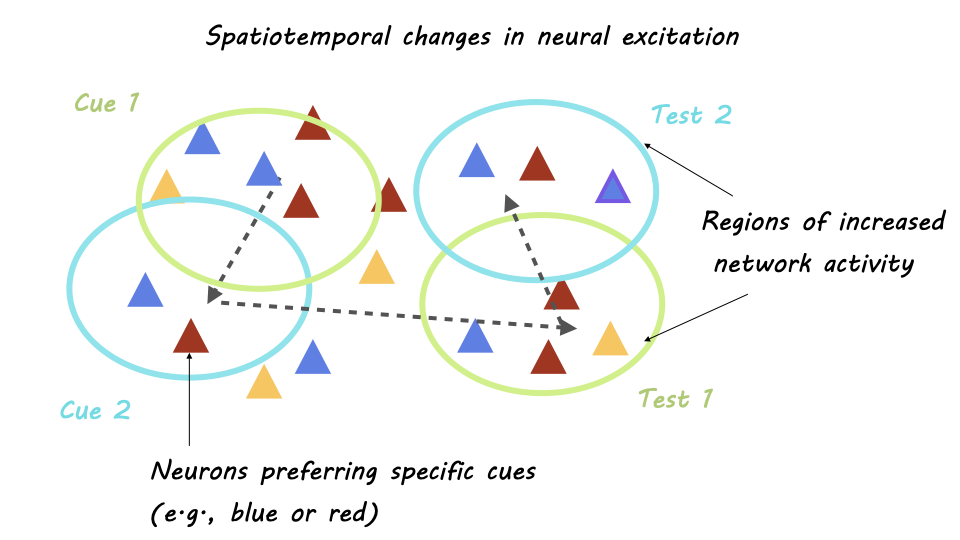

Burnout has also been associated with cognitive deficits. Those experiencing burnout are more likely to have attentional lapses and memory impairments, with effects often more pronounced in women than men (Morgan et al., 2011; Deligkaris et al., 2014) and may have more trouble switching attention between visual stimuli than non-stressed controls (Deligkaris et al., 2014). These cognitive and attentional challenges may lead to difficulties with work performance and the ability to feel rewarded and satisfied by the work (Liston et al., 2009).

What’s the connection between burnout and depression?

The symptoms associated with burnout are like those of depression (Schonfeld et al., 2015). Interestingly, reduced serotonin binding in the anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, and anterior insular cortex (regions involved in emotional processing), has been reported in the brains of those undergoing chronic occupational stress (Jovanovic et al. 2011). These brain regions, along with the serotonin system are involved to some extent in the pathology of depression, highlighting possible mechanistic overlaps. Although this relationship requires further investigation, similar attentional-behavioral changes have been reported between individuals with burnout and those with depression (Liston et al., 2009).

While burnout and depression may be highly correlated, there are some important distinctions. Depression is currently a diagnosable mental health condition, whereas burnout is not (Schonfeld et al., 2015). Additionally, burnout occurs in response to situational stress, while depression is not necessarily triggered by a specific event. However, it’s important to note that both conditions can require professional help.

How can we bounce back from burnout?

Recognizing you have burnout is an important first step. Give yourself grace and take time to care for your mental health. This can include seeing a therapist, taking breaks throughout the workday, exercising, practicing mindfulness, and trying to foster better work-life balance by engaging in non-work-related activities and social connections (Maslach et al., 2015).

Previous research in rodents has found that chronic stress impairs attention-shifting ability in rats and damages neurons in the prefrontal cortex, but these deficits are reversed after three weeks of relaxation (Arnsten AFT, 2009). Similarly, longitudinal brain imaging studies in humans have shown that cortical thinning and decreased functional connectivity of the prefrontal cortex and attention impairments can be reversed when stress exposure is reduced (Savic, et al., 20018, Deligkaris et al., 2014). This suggests that even though the effects of burnout are quite deleterious on the brain and body, there is room for improvement if stressful conditions can be managed.

While personal-level interventions are necessary, there must be change at the organizational level as well. For example, managers should be trained to recognize signs of burnout in their staff and companies should be encouraged to improve the work environment and conditions to foster a supportive work culture (Vladut et al., 2010). Ideally, individuals recognize the first signs of burnout and take steps to intervene, but chronic stress that manifests into burnout can be challenging to handle on your own. Considering professional support when burnout becomes an issue should be encouraged.

References +

Arnsten AFT. (2009). Stress signalgin pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and fuction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10: 410-422.

Blix, E., Perski, A., Berglund, H., & Savic, I. (2013). Long-term occupational stress is associated with regional reductions in brain tissue volumes. PLOS ONE 8: e64065. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064065

Deligkaris, P., Panagopoulou, E., Montgomery, A. J., & Masoura, E. (2014). Job burnout and cognitive functioning: A systematic review. Work & Stress, 28, 107–123. doi:10.1080/02678373.2014.909545

Golkar, A., Johansson, E., Kasahara, M., Osika, W., Perski, A., & Savic, I. (2014). The influence of work-related chronic stress on the regulation of emotion and on functional connectivity in the brain. PLOS ONE 9: e104550. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104550

Jovanovic, H, Perki, A, Berglund, H, Savic, I (2011). Chronic stress is linked to 5-HT1A receptor changes in functional disintegration of the limbic networks. Neuroimage, 55, 1178-1188.

Liston, C., McEwen, B. S., & Casey, BJ. (2009). Psychosocial stress reversibly disrupts prefrontal processing and attentional control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 912–917. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807041106

Miranda, F. (2022). The neural correlates of burnout: a systematic review. Digitala etenskapliga Arkivet.

Maslach, C., & M. P. Leiter, (Eds.). (2015). It’s time to take action on burnout. Burnout Research, 2, iv–v. doi:10.1016/j.burn.2015.05.002

Morgan, C. A., Russell, B., McNeil, J., Maxwell, J., Snyder, P. J., Southwick, S. M., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2011). Baseline burnout symptoms predict visuospatial executive function during survival school training in special operations military personnel. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 17, 494–501. doi:10.1017/S1355617711000221

Ogbonnaya UC, Thiese MS, Allen J. (2022). Burnout and engagement’s relationship to drug abuse in laywers and law professionals. J Occup Environ Med, 64: 621-627.

Oosterholt, B. G., Maes, J. H., Van der Linden, D., Verbraak, M. J., & Kompier, M. A. (2015). Burnout and cortisol: Evidence for a lower cortisol awakening response in both clinical and nonclinical burnout. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78, 445–451. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.11.003

Savic, I. (2015). Structural changes of the brain in relation to occupational stress. Cerebral Cortex, 25, 1554–1564. doi:10.1093/cercor/bht348

Savic, I, Perksi A, Osika, W. (2018). MRI shows that exhaustion syndrome due to chronic occupational stress is associated with partially reversible cerebral changes. Cerebral Cortex, 28: 894-906.

Schonfeld IS, Bianchi R. (2015). Burnout and depression: two entities or one? Journal of clinical psychology, 71:22-37.

Toker, S., Melamed, S., Berliner, S., Zeltser, D., & Shapira, I. (2012). Burnout and risk of coronary heart disease: A prospective study of 8838 employees. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74, 840–847. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31826c3174

Vladut, CI., Kallay, E. (2010). Work stress, personal life, and burnout. Causes, consequences, possible remedies: a theoretical review. Cognition, Brain, Behaviour, 14, 261-280. https://www.proquest.com/docview/856042813?fromopenview=true&pq-origsite=gscholar