Controlled Breathwork Improves Mood and Reduces Anxiety

Post by Leanna Kalinowski

The takeaway

Engaging in daily 5-minute breathwork exercises and mindfulness meditation improves mood and reduces anxiety. Cyclic sighing – a voluntary breathwork exercise that primarily focuses on exhales – showed the greatest benefits compared to other voluntary breathwork techniques.

What's the science?

Controlled breathwork techniques have emerged as a promising avenue for improving mood and reducing stress. Methods that involve passive observation of the breath, such as meditation and yoga, are common practices that have well-demonstrated mental health benefits. These practices have different physiological effects from voluntary breathing techniques, where inhaling and exhaling patterns are directly controlled. However, little is known about how passive and voluntary breathing techniques uniquely affect mental health. This week in Cell Reports Medicine, Yilmaz Balban and colleagues evaluated the difference between passive and voluntary breathing exercises and their effectiveness in improving mood, anxiety, and physiological measures.

How did they do it?

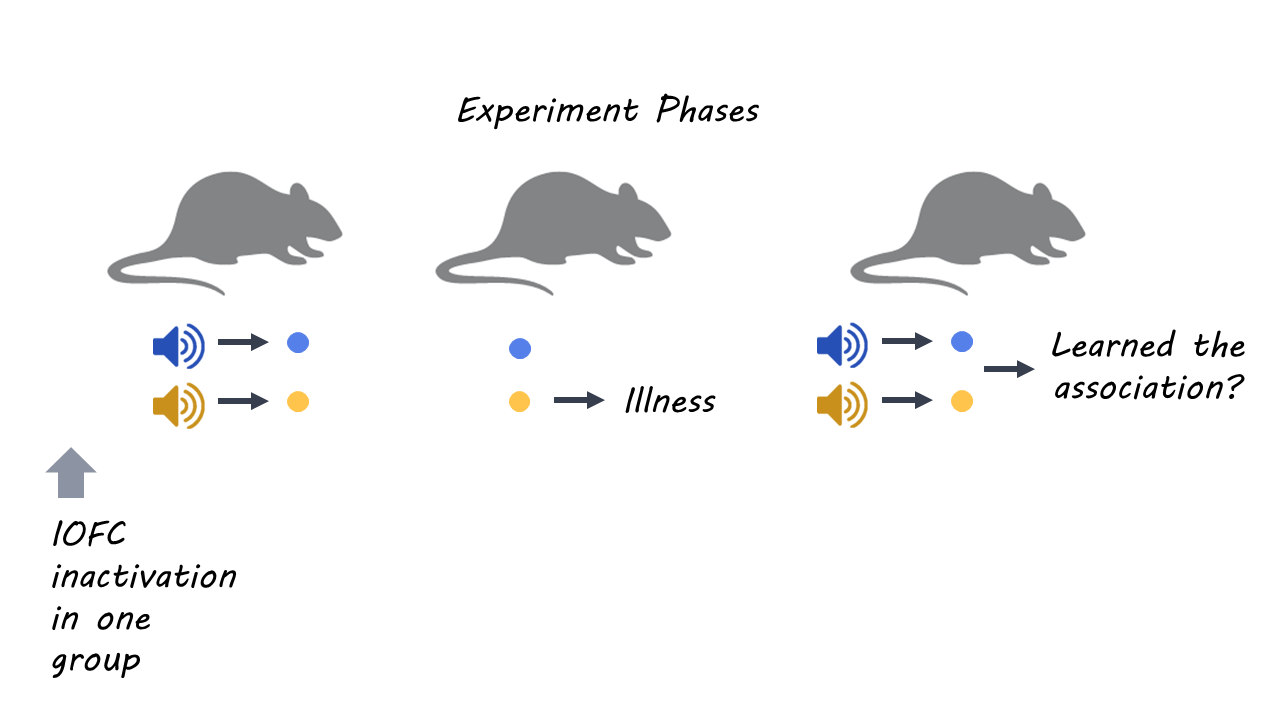

108 participants were divided into four groups – a mindful meditation (control) group and three voluntary breathwork (treatment) groups – and instructed to complete their assigned daily breathing exercise at home for 28 days:

1) Mindful Meditation (control group): Participants were instructed, for 5 minutes, to close their eyes and observe their breathing while focusing their mental attention on their forehead region. If their focus drifted from that region, they were told to first focus back on their breath, and then refocus back on their forehead.

2) Cyclic Sighing (breathwork group 1): Participants were instructed to, repeatedly for 5 minutes, inhale slowly until their lungs are expanded, inhale once more to maximally fill their lungs, and then slowly and fully exhale their breath.

3) Box Breathing (breathwork group 2): Participants were first instructed to take the “CO2 tolerance test”, which includes taking a full deep breath, exhaling as slowly as possible, and then timing how long it takes to empty their lungs. Then, repeatedly for 5 minutes, they inhaled for the same duration it took to empty their lungs in the CO2 tolerance test, held their breath for that same duration, then exhaled for that same duration, then held their breath again for the same duration.

4) Cyclic Hyperventilation with Retention (breathwork group 3): Participants were instructed to inhale deeply and then exhale by passively “letting their air fall out from the mouth”. They repeated this pattern for 30 breaths, after which they exhaled via the mouth and calmly waited with empty lungs for 15 seconds.

Participants completed two surveys that measured affect and anxiety at baseline and again after the experiment. They also wore a wrist strap during their breathing exercises that collected several physiological measures, including their daily resting heart rate, respiratory rate, and hours of sleep. These measures were collected remotely via a smartphone app.

What did they find?

The researchers found that, following 28 days of breathing exercises, all four groups experienced an increase in daily positive affect, a decrease in negative affect, and a reduction in anxiety. While there were no differences between the meditation (control) and breathwork groups in anxiety and negative affect changes, the three breathwork groups had a higher increase in daily positive affect compared to the meditation group. Upon evaluating the physiological measurements, researchers found a similar pattern: the three breathwork groups had a higher reduction in baseline respiratory rate than the meditation group. For both the positive affect and respiratory rate results, group differences were largely influenced by the cyclic sighing group, suggesting particularly beneficial effects for breathing techniques that emphasize exhaling. No other physiological changes were observed in any of the groups.

What's the impact?

Results from this study suggest that engaging in intentional breath control exercises (e.g., the cyclic sighing technique) provides more benefits to mood than passive breath observation exercises (i.e., mindfulness meditation). While all four breathing techniques were effective in improving mood and decreasing anxiety, daily 5-minute cyclic sighing shows the most promise in being a low-commitment approach to managing stress. Future studies should evaluate whether the consistent practice of these techniques, beyond one month, remains effective in improving psychological outcomes.