A Brain Region Critical in Creating Cognitive Maps

Post by Anastasia Sares

The takeaway

The lateral orbito-frontal cortex (lOFC), is a brain region in the frontal lobe, just above the eyes, that helps us interact with the world by mapping associations between different events. While previously it has been given the role of “deploying” these maps (deciding when to use them), this new study suggests that the lOFC might be involved in creating those association maps in the first place.

What's the science?

Reinforcement learning is how we develop knowledge through our interactions with the environment. When we perform actions, we get feedback about the results of those actions, and if they result in a reward, we are more likely to repeat those actions again later. Reinforcement learning can be divided into model-free learning, where we learn directly from the consequences of our actions, and model-based learning, where we create a map of associations (in other words, a model) that can help us make decisions based on context.

This week in Nature Neuroscience, Costa and colleagues tested what happens when the lOFC is taken out of commission.

How did they do it?

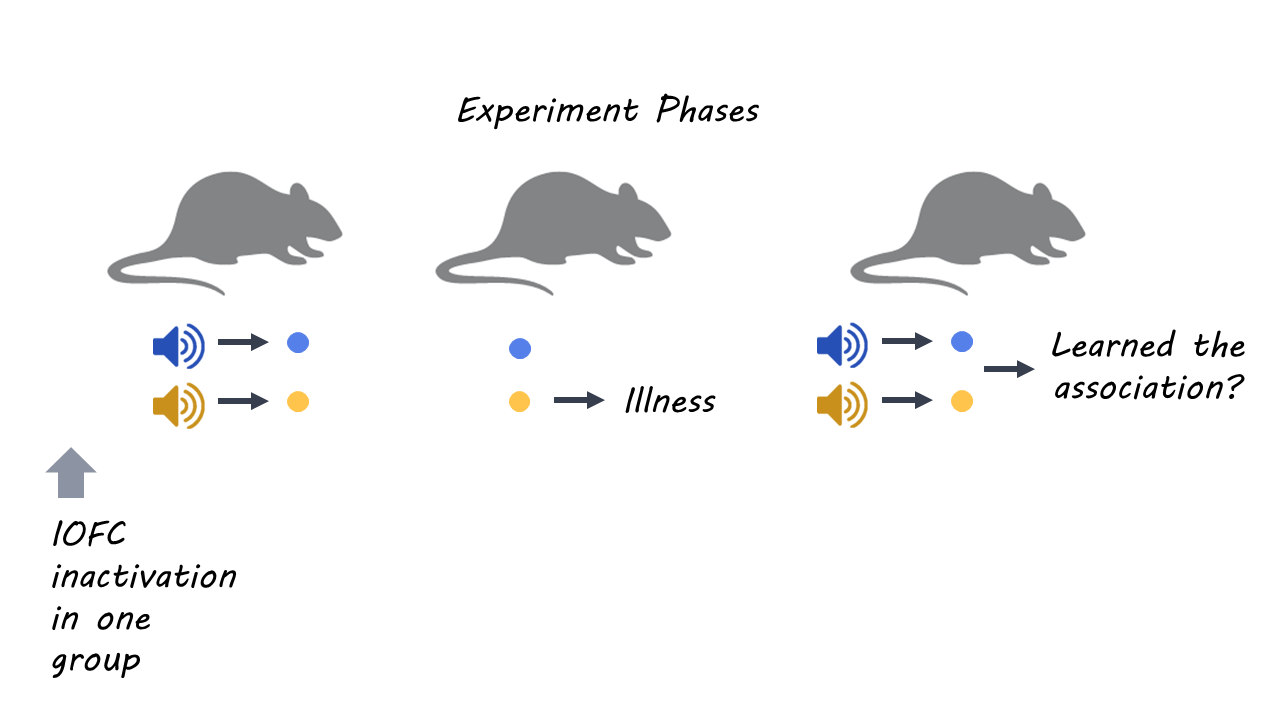

The authors first trained rats to associate sound stimuli with getting food pellets, with one sound predicting banana-flavored pellets and another sound predicting bacon-flavored pellets. The rats learned that sounds were associated with a food reward, but at this phase, there was no reason for them to learn the distinction between the two sounds.

In the second phase, both types of pellets were again given to the rats, but after they ate one kind of pellet (let’s say the banana one), they would be administered lithium chloride, which made them feel nauseous. Here, the rats learned a connection between one type of pellet and nausea, but the sounds were not involved.

In the final phase, the rats were again presented with the sounds, and the authors measured how long the animal searched for a food pellet after hearing the sound. The rats had never learned a direct association between the sounds and nausea, so they would have to create this connection themselves based on information from the first two phases. Specifically, they would need to rely on an internally-created “model” or associative map linking the relevant sound to the bad pellet (even though the type of sound had not mattered before).

Two groups of rats participated in this experiment. The first was a control group, and the second group had been bio-engineered (by applying a custom viral agent) so that the lOFC could be temporarily “turned off” by administering a drug just before the learning session in the first phase. If the lOFC was involved in creating association maps, then turning it off for in the first learning phase should make the rats unable to learn the association between sound cues and nausea. However, if the lOFC is only involved in “deploying” these association maps, then turning it off in phase 1 should have no effect on their ability to use them later.

What did they find?

When the control rats heard the specific sound that predicted the “bad” pellets (the ones that had made them nauseous), they did not go to the food bowl as often as when they heard the other sound. This means they had clearly learned the distinction between different sounds, the foods they signaled, and the predicted result of eating those foods, and were able to put this information together in the final test to guide behavior. In contrast, rats whose lOFC was deactivated in phase 1 reduced their trips to the food bowl for both sounds at test time. These rats thus had the ability to form a rudimentary map to guide behavior, however, this map lacked the specific information that would allow them to choose the “good” pellets and avoid the “bad” ones.

The authors also put the rats through an object recognition task, which required them to distinguish between new and old objects. In this case, the rats with the deactivated lOFC performed similarly to the control rats, indicating that the lOFC is not involved in basic learning.

Finally, the authors created some mathematical models to try and reproduce the results. They found that the best explanation of the impaired animals’ behavior was an imprecise mapping from sounds to pellet flavors during the first learning phase.

What's the impact?

Model-based reinforcement learning is a crucial function of the brain, and abnormalities in this system can lead to maladaptive behavior. For example, problems with association maps are present in mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, substance abuse, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Therefore, understanding more about how this area of the brain works may help us better diagnose and treat these conditions.