How Aversive Memories Are Stored and Retrieved

Post by Leanna Kalinowski

The takeaway

Researchers have found that neuronal ensembles in one brain region recruit presynaptic neurons in other regions during the retrieval of aversive memories.

What's the science?

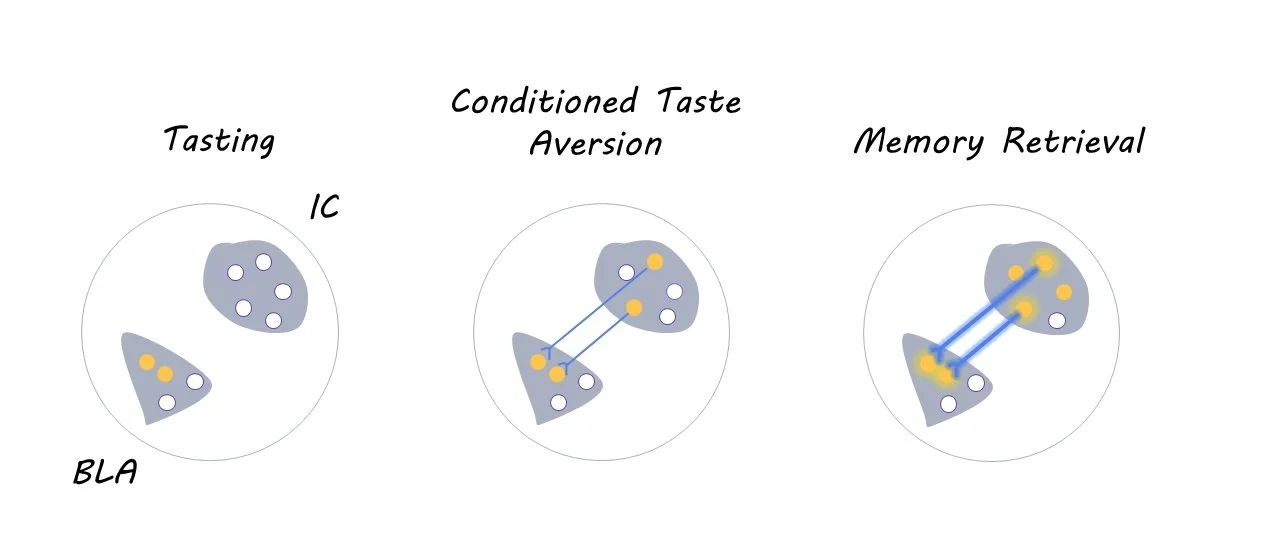

Each of our memories is stored in neuronal ensembles – sparse groups of co-active neurons – across multiple different brain regions. Previous research has shown that the allocation of memories to these brain regions is not a random process; it is dependent on the level of CREB protein expressed within individual neurons. However, it is unclear how these cross-region connections are organized at the time of learning to ensure that the neuronal ensembles from different brain regions are coordinated when the memory is retrieved. This week in Neuron, Lavi and colleagues tested whether allocating aversive memories to neurons in one brain region impacts memory allocation in interconnected brain regions in mice.

How did they do it?

First, the researchers injected mice with a combination of three viruses into the basolateral amygdala (BLA; experiment 1) or insular cortex (IC; experiment 2), which are two interconnected brain regions that are crucial for conditioned taste aversion memories. The first virus carried the CREB gene, which biases the allocation of memories to a random subset of neurons within the injected brain region. The second virus was the rabies virus coupled with mCherry (a fluorescent marker), which allows researchers to visualize the location of presynaptic neurons that project to the injected region via retrograde tracing. The third virus encoded TVA, which is a protein that is essential for the rabies virus to travel to presynaptic neurons.

Four days after the viral injections, the mice underwent a conditioned taste aversion task, which teaches mice to associate a particular taste with an aversive stimulus (i.e., illness). During the habituation phase of this task, which lasted three days, mice received a daily water ration for 30 minutes per day from two tubes. Then, on the following day, the plain water was replaced with sugar water, and the mice were subsequently treated with an injection of lithium chloride. This injection induced feelings of illness, thereby leading mice to develop a learned aversion to sugar water. Aversion to sugar water was then tested three days later, after which their brains were collected and analyzed for neural activity using c-fos immunohistochemistry.

To test whether these effects extend to other senses beyond taste (i.e., hearing), the researchers then injected the same three viruses into the BLA of a new cohort of mice and subsequently subjected them to an auditory fear conditioning task. In this task, mice were trained to associate an auditory stimulus (14kHz tones) with a foot shock. Aversion to the auditory stimulus was then tested three days later, after which their brains were collected and analyzed in the same manner as above.

What did they find?

Overall, the researchers found that the allocation of aversive memories in one brain region leads to the retrograde activation of presynaptic neurons (i.e., the target neuron sends a signal back to the presynaptic neuron) in other brain regions during memory allocation and retrieval. Specifically, using CREB to allocate taste aversion memories to the BLA leads to the recruitment of presynaptic neurons in the IC. This pattern was also observed in the opposite direction (i.e., allocating taste aversion memories to the IC leads to the recruitment of neurons in the BLA), suggesting that a bidirectional relationship between these two brain regions is necessary for coordinating taste aversion memory retrieval. Similar coordination was observed between the BLA and auditory cortex during auditory fear conditioning, demonstrating that these effects extend to other senses beyond taste aversion.

What's the impact?

This study uncovered the mechanisms that underlie cross-regional memory allocation and retrieval, particularly for aversive memories. These results may pave the way in better understanding how cross-regional memory coordination is disrupted in neurological and psychiatric diseases.