How Our Behavior Influences Productivity

Post by Leanna Kalinowski and Leigh Christopher

What blocks your productivity?

Have you ever wanted to get something done, but found yourself endlessly putting it off? Or, in an attempt to start the day off on a productive note, been paralyzed by your long list of tasks to do? These experiences have one thing in common: they involve shifts in your attention or motivation.

Feeling motivated can help us to stay productive, however, our motivation can wax and wane over time. And, sometimes, we simply don’t have the motivation needed to work at our best. We can also become easily distracted throughout the day, or develop bad habits that prevent us from achieving our goals. This is known as the intention-action gap - the concept that our intentions do not always translate into action.

In an ideal world, we would avoid distractions, work efficiently and accomplish everything we planned. However, as human beings, we’re susceptible to distractions and we have limited willpower. Fortunately, there are helpful strategies that we can use to aid in the development of better productivity habits. BrainPost partnered with Intelligent Change (creators of The Five Minute Journal) to highlight some of the top, scientifically-backed strategies that you can implement to stay on track.

Creating a simple plan to reduce the noise

Why is it so hard to accomplish what we want? Although it may seem like we know exactly what needs to be done, this can often be the first barrier to productivity - noise. There is so much going on in our day-to-day lives that our goals can seem overwhelming. This is why implementation intentions - a simple plan that states where, when, or what we will do- can be immensely helpful. One research study found that those who wrote down where and when they were going to exercise were more than twice as likely to follow through on their exercise plan. This research highlights that it’s not always about boosting inherent motivation. A simple cue in our environment, in this case, like the indication of where or when the action will take place, helps lead to the desired behavior, which then, in turn, encourages even greater motivation later on.

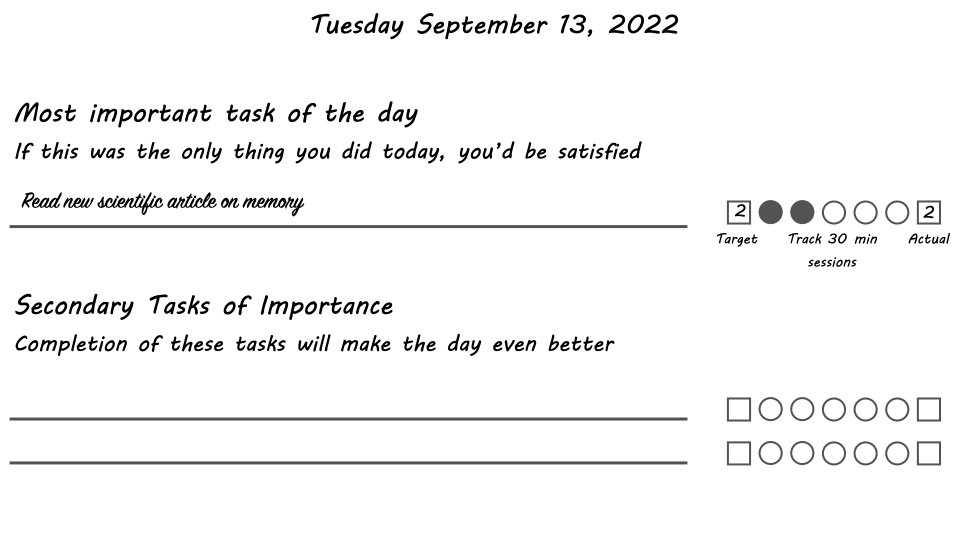

What else can help us filter through the noise? Another important, but often overlooked concept in productivity, is prioritization. By whittling down our to-do list to just a few or even one very important task, we simplify our lives and lighten our cognitive load. Choosing one task to focus on at a time can also reduce choice overload - when too many choices make it difficult to decide what to do, hindering action. Sometimes, one of the biggest challenges is identifying what is actually most important - and this can be especially uncomfortable when the most important thing is something we’ve been avoiding. This is why prioritizing the most important task to focus on for the day can be a powerful way to follow through on our goals.

Using sub-goals and progress monitoring to boost motivation

There are pros and cons to setting a significant goal, such as writing a graduate school thesis or training for a marathon. On one hand, difficult goals that require considerable effort lead to higher performance and motivation, because people feel a greater sense of accomplishment after completing something challenging. On the other hand, goals that are too challenging or that exceed the limits of one’s capabilities are more likely to be abandoned midway through. Chunking goals into smaller steps (i.e., setting “sub-goals”) can help make those larger goals more attainable while still retaining the overarching challenge and reward. For example, setting a goal to spend an hour a day working on your thesis can help to provide daily bursts of reward, keeping the sense of accomplishment and motivation going while working towards the larger goal of completion.

Whether you are setting sub-goals or powering through your larger goal, research shows that monitoring your progress can help improve your likelihood of success. There are several ways to ensure that progress monitoring is most effective. First, be sure to monitor the progress that is specific to the goal that you are trying to achieve: for example, if your goal is to finish a writing piece, focus your goal on metrics directly related to this (e.g., minutes spent writing) rather than metrics that are indirectly related or vague. Second, monitor your progress in a quantifiable way. While simply checking a box saying “I wrote today” can be motivating for some, it can be more helpful for others to assign numerical values to their progress, like the number of paragraphs written for example. Finally, be sure to physically record your progress, as this also helps to increase your chances of following through on your goal. Tracking your progress in a planner or journal, for example, is one great way to visualize how you’re moving forward.

The Productivity Planner, by Intelligent Change, leverages implementation intentions, prioritization, and time tracking.

Turning a behavior into a habit

Ultimately, productivity strategies can vary from person to person. The strategies offered here can be thought of as tools to help you stay on track when pursuing your goals, and some may stick better than others. Having a system in place to help with productivity can be powerful in developing good habits. This is because repeating certain behaviors can help to reinforce a habit by increasing motivation to perform the same action again, eventually leading to a more automatic (i.e. easier) experience. This process is known as a habit formation loop - a cycle whereby repeated behaviors become more naturally rewarding and easier to perform. Although staying productive is important in the accomplishment of our goals, we are only human, and not every day will be productive. This is why introducing some flexibility into goal-setting, and practicing acceptance when things don’t go as planned, can be just as important.

References +

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2

https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0003-066X.54.7.493

https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1348/135910702169420

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11138768/

https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fmot0000127

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5364185/

https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fbul0000025

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S074959781730256X#b0170

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17437199.2011.603640