Long-Term Memory Formation Occurs Differently During Wakefulness and Sleep

Post by Lincoln Tracy

The takeaway

Long-term memories can be formed while we are awake, not just while we are asleep. However, the quality of memory consolidation varies depending on whether we are awake or asleep.

What's the science?

Sleep has long been heralded as a key promotor of consolidating newly encoded information into actual memories. Recent research suggests long-term memory consolidation can also occur while we are awake, but the mechanisms of wakeful memory consolidation are not well understood. This week in PNAS, Sawangjit and colleagues explored how long-term memory formation following a novel object recognition (NOR) task occurs in rats that had slept or remained awake after the initial encoding period.

How did they do it?

Rats were placed in an open field area and allowed to explore two identical objects for 10 minutes to familiarize themselves with the room, the area, and the objects (encoding phase). Immediately after, the rats had a two-hour post-encoding (or consolidation) phase where they were either allowed to sleep or kept awake. One week later, rats were returned to the area for the retrieval phase, where one of the objects was novel (retrieval or recall phase). The authors compared the time the rat devoted to exploring the novel object in comparison to the old object they had seen the week before. Rearing behavior (i.e., the rat standing on its hind legs) was also analyzed to assess how environmental context contributed to memory recall.

First, the authors tested the effects of sleep and wakefulness on long-term memory formation and recall. Second, they investigated whether the hippocampus makes an essential contribution to long-term memory formation during both sleep and wakefulness. To do this, they injected muscimol, a GABA-A receptor agonist, into the dorsal hippocampus 30 minutes after the rats fell asleep (and at a comparable time for the rats who remained awake) after the initial encoding session. Memory recall was tested one week later. Third, they tested NOR memory recall in a different context to what the rats were originally exposed to. That is, the recall component took place in a different arena, in a different room, with a different experimenter observing the rats. Finally, they analyzed electroencephalography (EEG) recordings of rats that slept after the NOR task to identify the specific mechanisms contributing to sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Like the previous behavioral tasks, they also tested the effect of muscimol on these potential mechanisms.

What did they find?

First, the authors found that although the rats that were kept awake displayed some long-term memory recall after a week, rats that slept after the encoding phase spent more time exploring the new object and less time exploring the familiar object (i.e., enhanced NOR performance). This suggests wakeful long-term memory consolidation is less effective than sleep consolidation. In addition, the rats that slept displayed fewer rearing behaviors in the retrieval phase compared to the encoding phase, while the rats that stayed awake displayed the same level of rearing across both sessions. This indicates the rats who were kept awake had no recollection of spatial context. Second, the authors found muscimol administration during sleep decreased NOR performance and maintained a higher level of rearing behavior in retrieval testing. In contrast, rats that were kept awake and received muscimol displayed enhanced NOR performance and did not affect rearing behavior during retrieval testing. Taken together, this suggests hippocampal inactivation influences memory consolidation during sleep and wakefulness in opposite directions, as well as selectively preventing rearing behaviors during sleep.

Third, the rats who slept after encoding showed no improvements in NOR performance when tested in a different context, while rats that were kept awake displayed robust NOR performance during retrieval testing. This implies object memory after wakeful consolidation is less well integrated with the context in which the information is learned, meaning it can be retrieved more easily in a different context. This implication is corroborated by the changes in rearing behavior. Rats that slept displayed increased rearing behavior during retrieval testing, while rats that were kept awake displayed similar levels. Finally, the authors found sleep spindles and slow oscillation-spindle events were associated with enhanced NOR performance.

What's the impact?

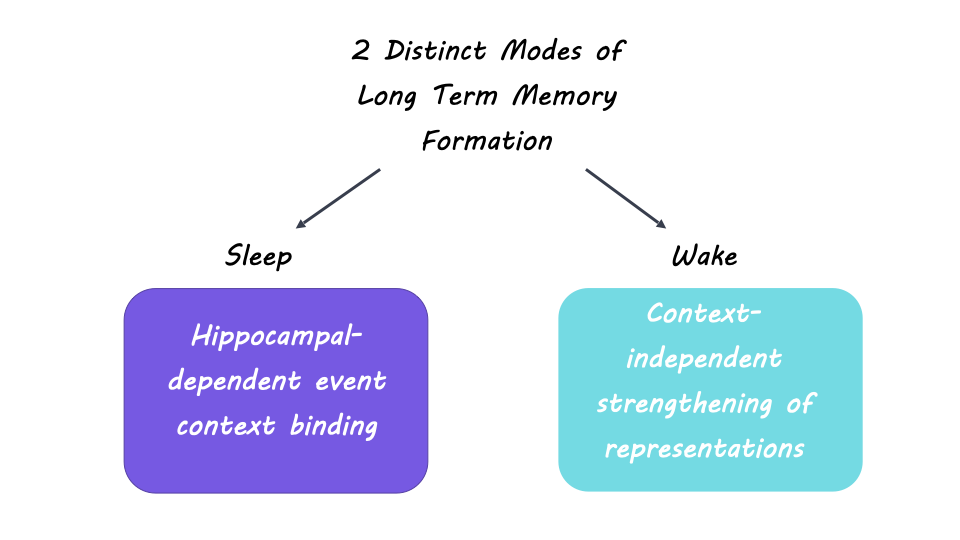

This study found there are two distinct ways that long-term memory formation can occur, albeit with differences in quality and quantity of memory encoding. During sleep, memory consolidation relies on hippocampal involvement and may involve linkages between event and context information. In contrast, wakeful consolidation is disrupted by hippocampal activation and implies that the context in which information was learned is less important.