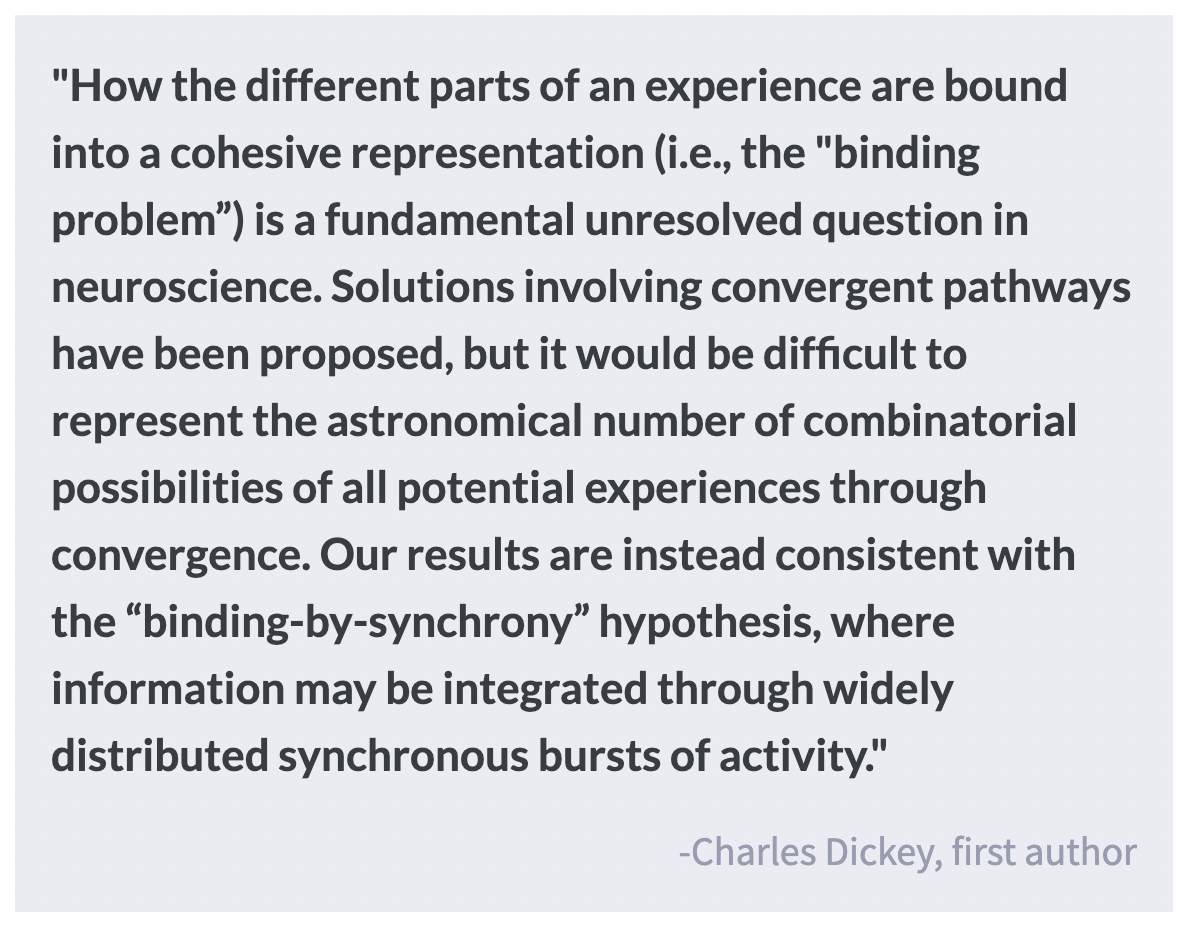

Ripples Facilitate Memory Recall via Widespread Synchronization of Brain Activity

Post by Leanna Kalinowski

The takeaway

The encoding, consolidation, and retrieval of memory requires the integration of multiple regions across the cortex. High-frequency brain oscillations, called “ripples”, may help to organize activity across these regions into a coherent representation.

What's the science?

Different elements of a memory are stored in different regions across the brain. Therefore a coordination of brain activity is required whenever a memory is consolidated, encoded, or retrieved. While this coordination is not yet fully understood, it is believed that these regions become synchronized via high-frequency brain oscillations called “ripples”. This week in PNAS, Dickey and colleagues used intracranial recordings in humans to measure ripple patterns during sleep, waking, and memory recall.

How did they do it?

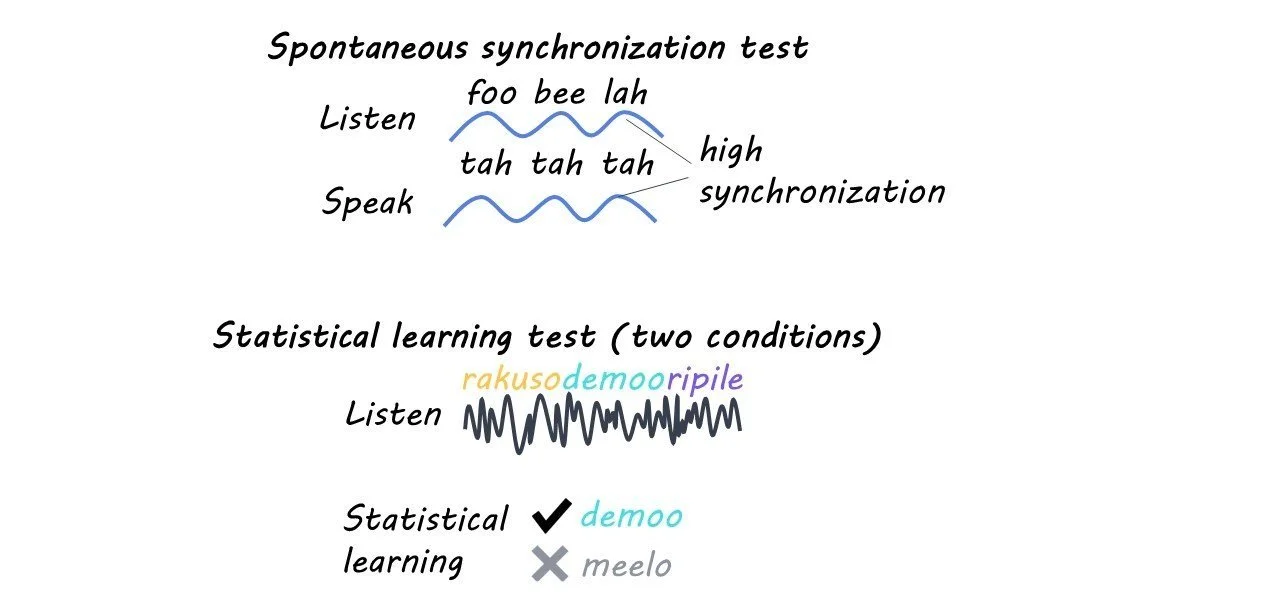

The researchers used data from 25 participants who already had electrodes surgically implanted into their brains for an unrelated medical issue (i.e., treatment-resistant epilepsy). This procedure, called stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG), is used to measure activity in regions deeper than what regular electroencephalography (EEG) can reach. In order to study healthy brain activity, they excluded data that was suspected to be related to underlying epilepsy. They measured ripple patterns from the cortex and hippocampus during three key periods: (1) during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, which is when the brain replays and sorts through memories for consolidation into long-term storage, (2) during waking, which is when information is transferred from the cortex to the hippocampus for memory encoding, and (3) during memory recall.

They then evaluated memory recall by having participants undergo the paired-associated memory task. In this task, participants first encoded eight pairs of words (e.g., “moon” + “mouth”) and were subsequently cued with one word from each pair (e.g., “moon”) to immediately recall the second word in the pair (e.g., “mouth”). After a 60-second delay with distraction, they were once again asked to recall the second word in the pair. This process was repeated until each participant attempted to recall about 100-160 unique word pairs in total.

What did they find?

The researchers found that ripples couple (i.e., occur within 500 ms of each other) and co-occur (i.e., have > 25 ms of activity overlap between these ~70 ms long events) across multiple lobes and both hemispheres during both NREM sleep and waking. They also found an increase in ripple co-occurrences between cortical sites and between the cortex and hippocampus during the memory recall task. These ripples phase lock with neuron firing (i.e., synchronize individual neuron activity) and phase synchronize with each other (i.e., synchronize activity across brain regions) across short and long distances.

What's the impact?

Taken together, these results demonstrate a mechanism by which the brain synchronizes activity across multiple cortical regions, which may help to integrate different components of a memory. This synchronization is not impacted by distance, including instances where both hemispheres of the brain are activated. Further work is needed to assess how ripples may help with the integration of brain activity for neural events beyond memory.