How Sleep Facilitates Relational Associative Memory

Post by Andrew Vo

The takeaway

Sleep plays a critical role in our ability to make connections among indirectly learned but overlapping items in our memories. Building a theoretical neural model that can learn and simulate sleep states revealed specific mechanisms by which sleep may improve associative memory.

What's the science?

Relational memory refers to the ability to form associations between individual items. An important feature of relational memory is transitive inference, the ability to form associations between indirectly learned but overlapping items. For example, indirectly learning that A→C after directly learning that A→B and B→C. Previous research has suggested that sleep is important in forming such memories. The exact mechanisms underlying this process are not entirely clear, however. This week in Journal of Neuroscience, Tadros and Bazheno build a thalamocortical network to test how sleep might strengthen relational memories.

How did they do it?

The authors built a computer model of a thalamocortical network that could learn a relational memory task as well as simulate awake/sleep states. The network contained a cortex, composed of two layers of neurons that represented the primary visual cortex and associative cortex, and thalamus. Excitatory and inhibitory connections among neurons were randomly modelled. Network states were simulated by changing levels of neuromodulators, such as acetylcholine and GABA, until neuron firing rates became characteristic of different sleep cycles.

The relational memory task was comprised of three stages: supervised training, unsupervised training, and sleep. During supervised training, each of six individual items was stimulated in cortical layer 1 followed by layer 2, forming network pathways that represented these items. Next, during unsupervised learning, pairs of items were stimulated at the same time to induce associative learning between individual items. During a sleep phase, neuromodulator levels were changed to simulate slow oscillation neuron firing typical of slow-wave sleep and no stimulation was provided. Finally, the network’s ability to learn and recall direct and indirect relational memories following sleep was tested by stimulating each individual item in layer 1 and measuring responses in layer 2.

What did they find?

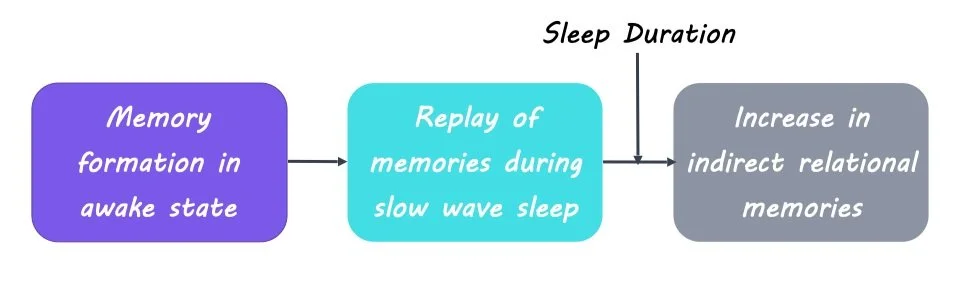

The authors found that following supervised training, stimulation of a given item in layer 1 induced corresponding activity for that item measured in layer 2. After unsupervised training, they observed an increase in direct but not indirect relational memories. Stimulation of a given item in layer 1 led to activity in layer 2 that corresponded only to directly associated items. It was only after a sleep phase that the network demonstrated increases in indirect relational memories. Stimulation of a given item in layer 1 now produced activity in layer 2 corresponding to indirectly associated items. This sleep-related improvement in relational memory was modulated by the length of training and the duration of sleep. These findings reveal that sleep is necessary for the formation of indirect relational memories.

To investigate the exact mechanism by which sleep can improve relational memory, the authors looked specifically at neuron spiking events during slow oscillations that were considered replay events. These replay events are related to the reactivation and consolidation of a memory. The authors found that the number of replay events was correlated with the strengthening of neural connections, suggesting that the replay of memory traces during sleep underlies the formation of not only direct but also indirect relational memories.

What's the impact?

The present study highlights the importance of sleep in our ability to form connections between indirectly learned but overlapping memories. It also demonstrates how building models of the brain that simulate different states can allow for controlled testing of specific hypotheses about human cognition.