Neurons Detect Cognitive Boundaries to Separate Memories

Post by Andrew Vo

The takeaway

We experience our lives as a continuous stream that is organized and stored in our memories as discrete events separated by cognitive boundaries. A neural mechanism in the medial temporal lobe (MTL) detects such boundaries as we experience them and allows us to remember the ‘what’ and ‘when’ of our memories.

What's the science?

How is our continuous experience of the world transformed into discrete events separated by boundaries in our memories? Whereas we have a clear understanding of how the brain encodes our spatial environments with physical boundaries, the neural mechanism by which nonspatial memories are shaped by abstract event boundaries remains unknown. This week in Nature Neuroscience, Zheng et al. recorded neuronal activity within the MTL of human epilepsy patients and tested their memories for video clips separated by different types of event boundaries.

How did they do it?

The authors recorded single-neuron activity within different regions of the MTL (including the hippocampus, amygdala, and parahippocampal gyrus) of 20 epilepsy patients as they performed a task. During an encoding phase, individuals watched 90 distinct and novel video clips that contained either no boundaries (i.e., a continuous clip), soft boundaries (i.e., cuts to different scenes within the same clip), or hard boundaries (i.e., cuts to different scenes from different clips). During a scene recognition phase, individuals were presented with single static frames (either previously presented ‘target’ clips or never-before-seen ‘foil’ clips) and asked to identify the frames as either ‘old’ or ‘new’ along with a confidence rating. During a time discrimination phase, individuals were shown two old frames side by side and asked to indicate the order they had previously appeared along with a confidence rating.

What did they find?

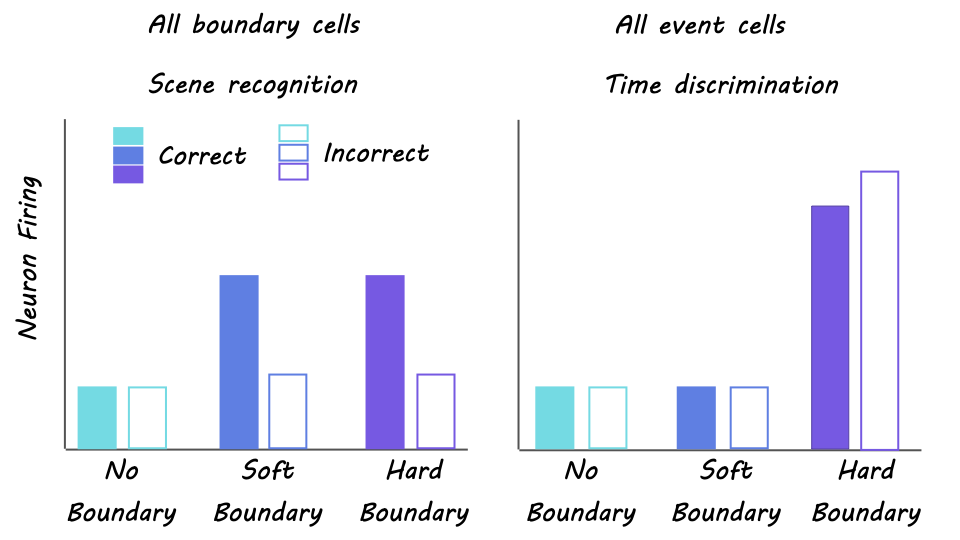

Scene recognition accuracy did not differ between boundary types. In contrast, time discrimination accuracy was significantly worse when discerning the order of frames separated by hard boundaries compared to soft boundaries. These findings suggest a tradeoff effect in which hard boundaries improve recognition but impair temporal order memory. The authors identified ‘boundary cells’ as those neurons in the MTL that showed firing rate increases following both soft and hard boundaries whereas ‘event cells’ were those neurons that responded only to hard but not soft boundaries. The level of boundary cell firing rate during encoding predicted later scene recognition accuracy, while the coordination of event cell activity with ongoing oscillations in the brain predicted later time discrimination performance. When examining neural state shifts (i.e., changes in the population activity across boundary-responsive neurons), larger shifts were positively related to improved recognition accuracy but negatively related to time discrimination—revealing a neural mechanism for the tradeoff between recognition and temporal order memories.

What's the impact?

This study revealed a neural mechanism in the MTL that responded to boundaries separating discrete events and helped to shape the content and temporal order memories for these events. A particular highlight of this paper is the use of single-neuron recordings in human patients, which allows for a more direct study of memory-related brain activity compared to less invasive approaches such as functional MRI or EEG.