Brain Activity in the Mesolimbic Network is Related to Affective Behaviour

Post by Negar Mazloum-Farzaghi

The takeaway

The brain mechanisms underlying affective behaviours like smiling, laughing, or expressing discomfort are critical to everyday life. This research shows that there is a distributed network of brain regions associated with different affective behaviors, and it's possible to differentiate these behaviors from neutral ones using brain activity recordings.

What's the science?

Affective states and our associated behaviors are an essential part of daily life. However, the underlying neurological mechanism of affective behaviours remains unclear. Previous studies have found that different affective behaviours are related to distinct patterns of spatial brain activity in the mesolimbic network, with certain brain regions playing a more critical role in some affective behaviours compared to others. Moreover, it remains unclear whether different spectral patterns (frequency bands) of activity in the mesolimbic network can distinguish one affective state from another. This week in Nature Human Behaviour, Bijanzadeh and colleagues examined the brain mechanisms underlying naturalistic affective behaviours from epilepsy patients who had intracranial EEG (iEEG) electrodes implanted in their mesolimbic network.

How did they do it?

The authors aimed to investigate whether changes in specific frequency bands (i.e., spectral features) in specific mesolimbic network brain regions (i.e., spatial features) would create ‘spectro-spatial’ patterns across the mesolimbic network, which would ultimately allow for the distinction between naturalistic affective positive and negative behaviours. To investigate this, the authors obtained 24-h audiovisual recordings and continuous iEEG data from 11 hospitalized participants with epilepsy. They analyzed 116 hours of behavioural and neural data from these participants who had electrodes placed in at least three mesolimbic structures (insula, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), amygdala, and hippocampus). Behaviours were categorized as positive affective behaviours (smiling, laughing, positive verbalizations), negative affective behaviours (pain-discomfort, negative verbalization), and neutral behaviours (control condition; minimum 10-minute periods where the participants showed neither negative nor positive affective behaviours).

The authors aligned each participants’ neural and behavioural data and extracted the spectral power in brain frequency bands from the electrodes in their mesolimbic structures. The average power in each frequency band (spectral features) for each electrode (spatial features) was computed and the two sets of features combined were referred to as the spectro-spatial features. Next, using statistics and machine learning methods, the authors trained models (binary random forest models) on the spectro-spatial features for the behaviours for each participant to determine whether models could distinguish between affective behaviours and neutral behaviours. Then, the authors examined which mesolimbic spatial features influenced the performance of the models.

What did they find?

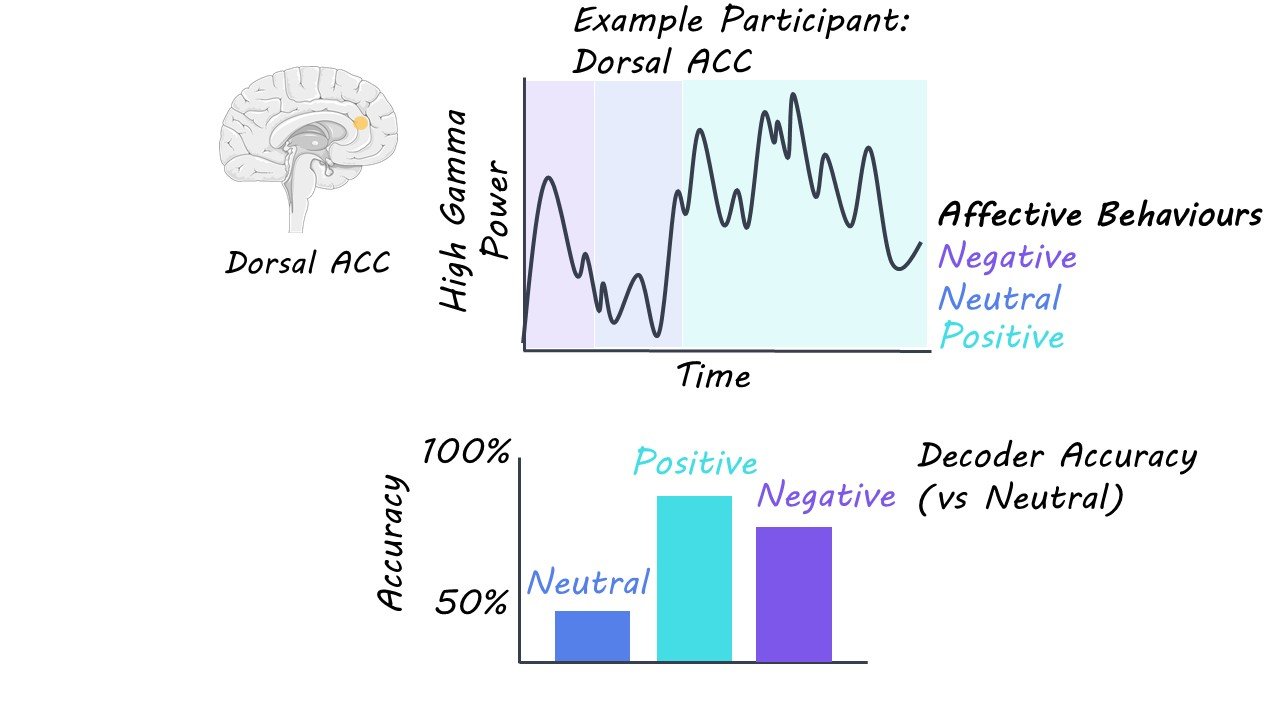

The authors found that, at the individual level, models were able to successfully decode positive (up to 93% accuracy) and negative affective (up to 78% accuracy) behaviours from neutral behaviours significantly greater than chance, and the group-level analysis replicated those results. Moreover, it was found that affective behaviours were associated with changes in activity in the mesolimbic network. That is, affective behaviours were related to increased high-frequency (gamma) and decreased low frequency bands (theta, alpha, beta).

Certain regions of the mesolimbic system (insula, ACC, hippocampus, and amygdala) were found to contribute more strongly to both positive and negative affective behaviours, compared to other regions (OFC). This finding suggests that increased gamma activity in these brain regions during both positive and negative affective behaviours may reflect emotional arousal in general. However, the results also revealed that distinct structures of the mesolimbic system may contribute to positive and negative affective behaviours in different ways. For example, increased gamma activity in the ventral ACC, dorsal ACC, and hippocampus was related to positive affective behaviours. In contrast, increased gamma activity in the amygdala was related to negative affective behaviours. Thus, this research suggests that there is a distributed network of brain regions that are associated with different affective behaviours in the mesolimbic system.

What's the impact?

Using statistical and machine learning methods, this study found that spectro-spatial features of brain activity in the mesolimbic network are related to naturalistic affective behaviours. This study further elucidates the neural mechanisms at play in the mesolimbic network. Advancing decoding models to be able to relate neural signals to more complex emotions will allow for more refined brain models of affective behaviours which may be used to inform treatments for mental health disorders.