The Impact of a Global Pandemic on Brain, Behavior and Mental Health

Post by Lani Cupo

What did we learn?

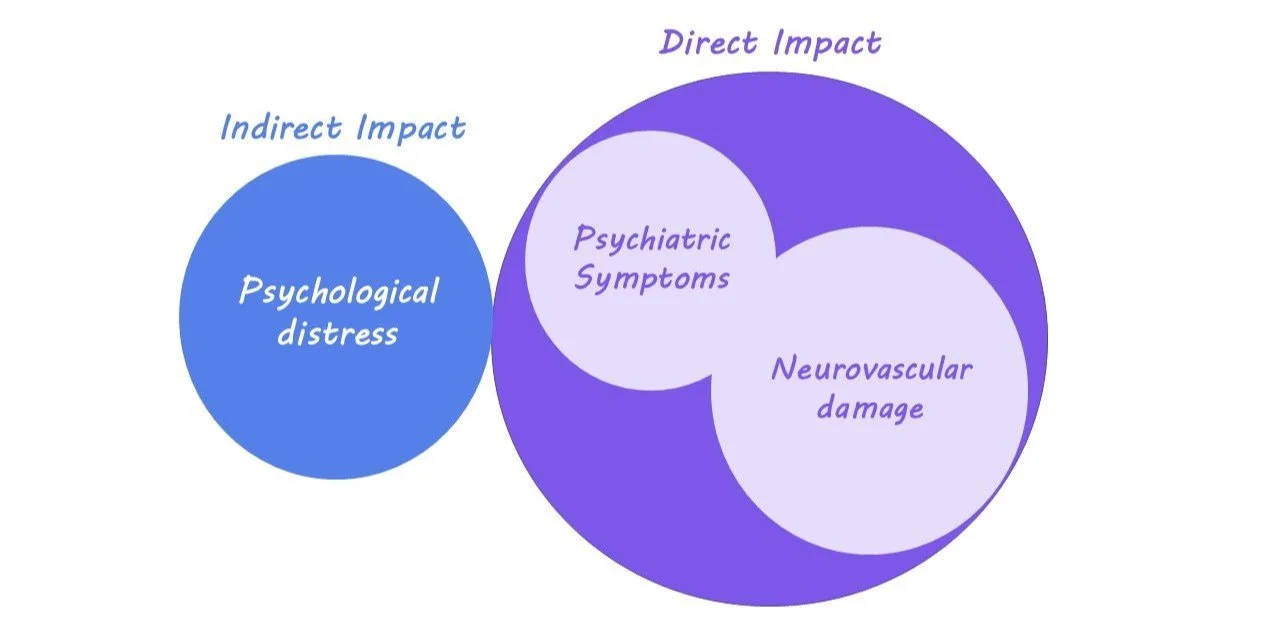

Along with the heavy toll the COVID-19 pandemic has taken on physical health around the globe, there is a rising mental health cost as well, the effects of which are still being discovered. One contributing factor is the experience of increased psychiatric symptoms (e.g. impaired attention, anxiety, insomnia, and depression) among survivors of COVID-19, with some evidence for more severe COVID-19 symptoms being associated with more severe psychiatric symptoms. We also gained a deeper understanding of how the virus affects brain function at the biological level. COVID damages neurovasculature resulting in damage to the blood-brain barrier. The mechanism of action by which COVID impacts the neurovasculature is still unknown, however, it may be through a protein enzyme produced by the virus. However, even those uninfected by the COVID virus are experiencing higher rates of psychological distress during the pandemic, with one study in Israel finding young, unemployed women were at the highest risk for experiencing worsened mental health. Even in the workplace, research indicates that remote work has an impact on team collaboration, leading to more asynchronous communication, such as messages and emails as opposed to synchronous meetings, with employees becoming more siloed. This isolation could contribute to worsened mental health outcomes for those working from home. Overall, the pandemic and measures taken to control the virus can contribute to worsened mental health among survivors, their loved ones, and the general population, the effects of which are still unfolding.

What's next?

As much of the world scrambles to respond to new variants and organize the distribution of COVID tests and vaccines, attention must be paid to not only the direct consequences of the virus but the indirect impact on mental health as well. Even as there are advancements in treating and preventing COVID-19, the long-term psychiatric consequences that are starting to emerge cannot be disregarded. Mental health is not separate from overall public health, but rather intricately connected. Future research will only continue to uncover insights on how COVID-19 is impacting our brain health as the pandemic unravels.