Uncovering How Sleep Affects Memory and Brain Function

Post by Elisa Guma

What did we learn?

Sleep is an important part of our daily routine and a fundamental building block for our physical and mental health. Further, there is no major psychiatric disorder in which sleep is not affected. Although its complex physiology is not yet fully understood, recent findings suggest that during sleep, the brain is able to clear neurotoxins that accumulate during waking hours. Researchers have observed a dramatic increase in the volume of the interstitial system – the fluid-filled space that surrounds the cells of the brain – during sleep, which facilitates the flow of fluids through the brain, increasing the clearance rate of neurotoxins. The rate of clearance can be halted by just one poor night of sleep, leading to an accumulation of neurotoxic proteins in the brain. These neurotoxins include proteins such as B-amyloid, tau, and a-synuclein, whose pathological accumulation has been associated with the neurodegenerative diseases Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. This provides compelling evidence for the role of sleep in keeping our brain healthy and suggests that the disruption of adequate toxin clearing due to poor sleep may be a risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases.

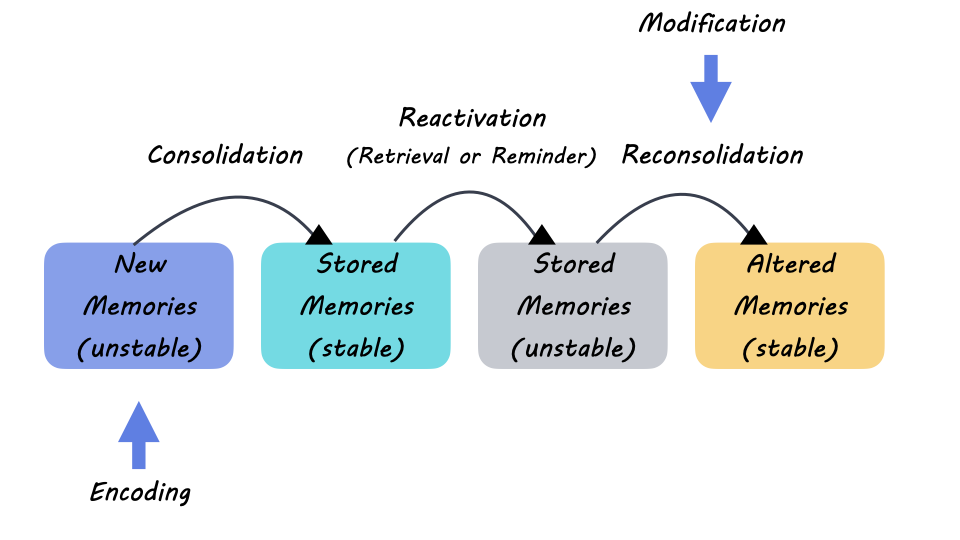

Sleep also plays a critical role in consolidating experiences into long-term memories. This year Skelin et al. uncovered that in order to support this process, the hippocampus produces a specific pattern of neural activity during sleep, sharp-wave ripples, characterized by large, fast, waves of activity, which stimulate high-frequency neuronal activity in regions of the memory circuit, the amygdala and temporal lobe. The activity of hippocampal neurons during sleep appears to act in concert with distant brain regions to coordinate the consolidation of memory.

What's next?

These advances made in our understanding of sleep physiology help us to understand its critical role in supporting our health and wellbeing. Future work is needed to uncover the relationship between poor sleep and risk for psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. Maintaining healthy sleep habits is not always an easy task, but here are a few suggestions for good sleep hygiene below (more here).

View sunlight in the morning by going outside, and do it again the later afternoon prior to sunset to help entrain your circadian clock

Try to maintain a consistent sleep schedule

Avoid caffeine within 8-10 hours of bedtime

Avoid viewing bright lights, especially bright overhead lights between 10 pm and 4 am

Limit daytime naps to less than 90 minutes

Keep a cool bedroom

2022 should be an exciting year in furthering our knowledge of how sleep impacts our brain function and our day-to-day lives.