A Step Towards Personalized Classification in Epilepsy

Post by Andrew Vo

The takeaway

Treating patients with temporal lobe epilepsy is challenging due to the high degree of individual variability along the disease spectrum. Using machine learning and data-driven analysis of disease factors may allow for individualized patient diagnosis and care.

What's the science?

Despite sharing a common diagnostic label, patients with drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) often display widespread and non-overlapping brain changes. Large individual variation along the disease spectrum has made it difficult to accurately characterize TLE patients and predict treatment responses using traditional “one-size-fits-all” group-level analyses. This week in Brain, Lee et al. applied machine learning to brain imaging measures to estimate the expression of TLE “disease factors” and tested how well these factors predicted clinical outcomes in TLE.

How did they do it?

The authors first obtained magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brains of a large group of TLE patients. These non-invasive MRI measures described different structural and microstructural properties of the brain, including cortical thickness, myelin (white matter) changes, and gliosis (scarring in response to neuronal damage). They then applied machine learning to these data. Latent Dirichlet allocation is an unsupervised machine learning technique that estimates the co-expression of disease factors (i.e., patterns of disease-related brain changes) in each patient. Unlike more traditional approaches that aim to classify patients into a single subtype, the analysis technique used here allows multiple disease factors to be expressed to varying degrees in each patient. The authors determined the specificity of identified disease factors by estimating their expression in groups of healthy and other disease (i.e., frontal lobe epilepsy) control groups. Finally, they tested how well these disease factors could predict individual patient drug response and seizure outcomes after surgery, as well as the degree of cognitive dysfunction.

What did they find?

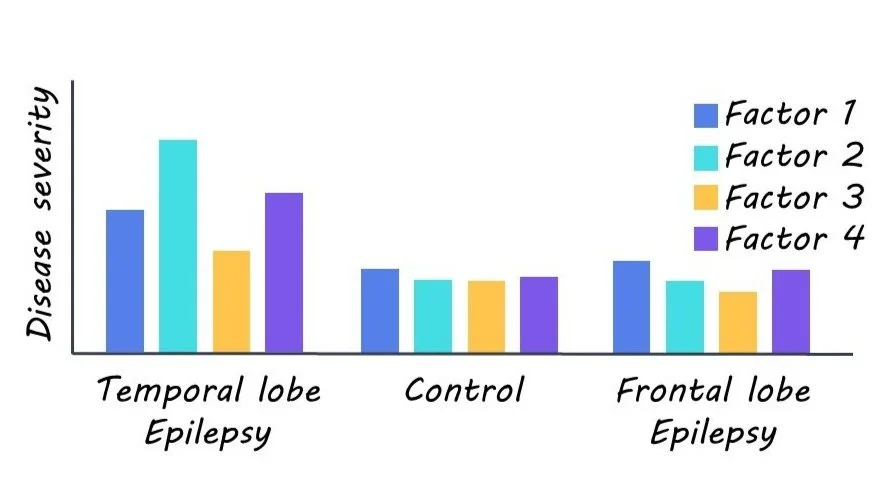

Four latent disease factors were identified. All factors were expressed to varying degrees in each TLE patient, not at all in healthy controls, and negligibly in frontal lobe epilepsy, thus highlighting the specificity of their findings. Factor 1 was characterized by microstructural changes, myelin loss, and atrophy largely in the hippocampus. Factor 2 was predominately marked by gliosis in paralimbic and hippocampal regions. Factor 3 was distinguished by bilateral neocortical thinning. Lastly, Factor 4 was largely marked with bilateral microstructural changes and minimal hippocampal changes.

The identified disease factors were then used to train classifier models, which predicted individual patient drug response and surgical outcome with 76% and 88% accuracy. Notably, classifiers trained on these disease factors out-performed untrained classifiers. Similarly, these disease factor-trained models could more accurately predict individual cognitive dysfunction (assessed in terms of verbal IQ, memory, and visuomotor learning) than baseline models.

What's the impact?

This study illustrated how using a machine learning approach can improve the characterization and prediction of clinical outcomes in TLE. Rather than classifying patients into a specific subtype, the strategy used here allows individuals to be represented along multiple dimensions that better capture their complex underlying pathology. Considering individual variability along the disease continuum will allow for personalized care and improved prognosis not just in TLE but other heterogeneous disease groups.