Numerosity Processing Across Cortical Layers in Parietal Cortex

Post by Lina Teichmann

The takeaway

Different cortical layers in the brain have different response patterns when processing quantities of items (i.e. numerosity). Cortical layers from different brain regions tend to increase in response specificity from central towards deep and superficial layers.

What's the science?

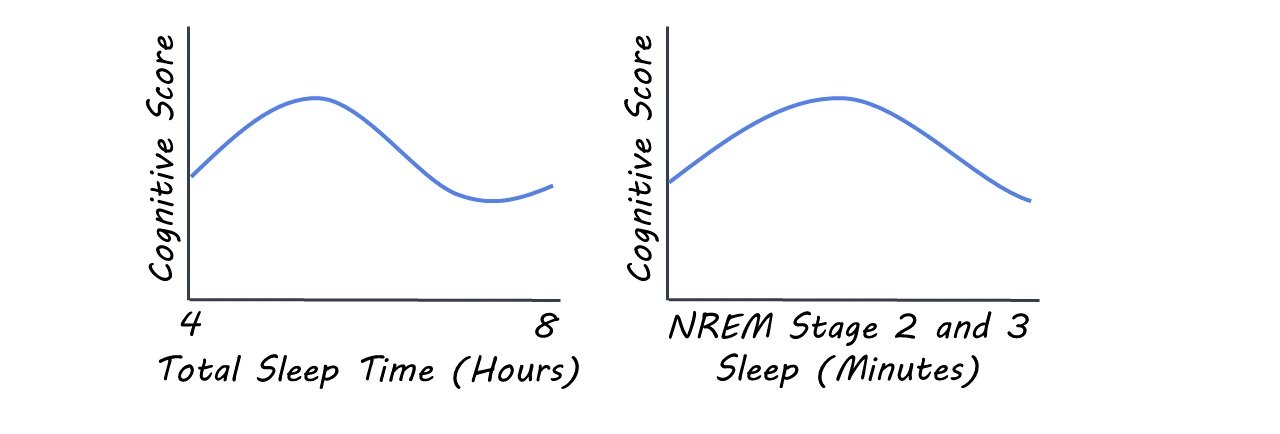

Numerosity processing allows us to determine the size of a group of items and is an essential ability in everyday life. Previous studies have shown that numerosity processing involves a network of specialized areas in the brain. Some of these areas, such as the parietal cortex, contain neuronal populations that prefer (respond strongly to) a specific numerosity, while numerosities that are further away from the preferred numerosity evoke a weaker response. The preferences of a neuronal population can be summarized by a tuning curve that shows how strongly a population responds to different numerosities. The width of the tuning curve indicates the numerosity preference of a given population: If the tuning curve is narrow — for example only having a peak at numerosity 3 but a sharp drop for neighboring numerosities (2 and 4) — the tuning response is very specific.

In the visual cortex, it has been shown that the specificity of neural responses varies across cortical layers, with both deep and superficial layers showing increased specificity in comparison to central layers. This week in Current Biology, van Dijk and colleagues examine whether this principle holds beyond the visual cortex by examining the specificity responses of neuronal populations in the parietal cortex that are tuned for specific numerosities.

How did they do it?

Seven healthy volunteers viewed different numbers of dots displayed on a screen while their brain activity was recorded using a 7 Tesla MRI scanner. The number of dots increased and decreased over time. Using the functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) time-series data, numerosity tuning was modeled for different voxels (3D “pixels” in the MRI image). That resulted in a preferred numerosity and tuning width for voxels in each cortical location and depth for every participant. First, the authors examined the preferred numerosity and tuning width in different cortical layers. Then, they investigated the width profiles across cortical depths.

What did they find?

There are two main findings. First, the results show that across cortical depths in the parietal cortex, the specificity of numerosity responses decreases as numerosity preference increases, replicating earlier findings. For example, for a neuronal population preferring numerosity 5, the specificity is lower (i.e., larger tuning width) than for neuronal populations preferring numerosity 3. This pattern is consistent across cortical depths. Second, tuning profiles for preferred numerosity 2 and 3 showed that deeper and superficial layers have smaller tuning widths than in the central layers. This indicates that response specificity increases as you move away from central layers towards deep and superficial layers.

What's the impact?

Using numerosity processing as a tool to examine response specificity, the study provides evidence that specificity increases as we move away from central layers in the parietal cortex. This highlights that the response structure across cortical layers in the parietal cortex is similar to those in visual cortex, suggesting that processing across cortical depths is organized in a similar way throughout the cortex.