Overlapping Neural Circuitry of Traumatic Brain Injury and Trauma-Related Psychiatric Disorders

Post by Amanda McFarlan

What's the science?

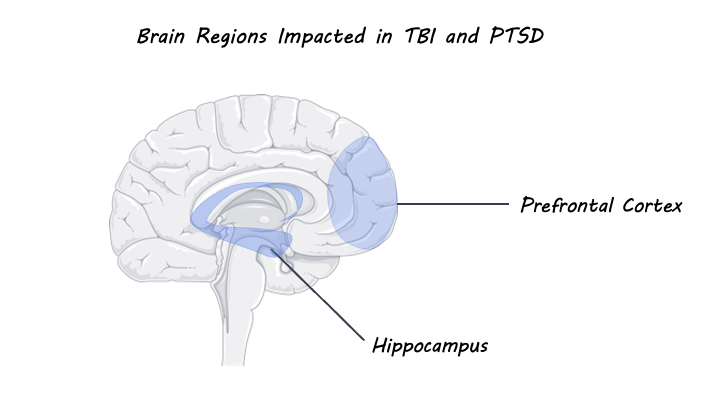

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) occurs after sudden trauma to the brain and can result in physical outcomes including white matter degradation, neuronal loss and neuroinflammation as well as emotional and cognitive responses. TBI-related outcomes including emotion dysregulation have been shown to overlap with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a psychiatric disorder that can occur after witnessing or experiencing a traumatic event. Indeed, neuroimaging studies have shown that TBI and PTSD are both associated with changes in connectivity and activation of prefrontal and subcortical brain areas that are involved in emotion regulation. This week in Biological Psychiatry, Weis and colleagues discussed the role of emotion dysregulation in TBI and PTSD outcomes.

What do we already know?

It has been shown that post-injury outcomes that follow TBI are associated with an increased risk for the development of persistent postconcussion syndrome (PCS) and psychiatric conditions including PTSD, major depressive disorder, general anxiety disorder, and substance use disorder. Researchers have proposed that this increased risk may be due to the presence of acute or chronic emotion dysregulation that occurs as a result of the physical and emotional trauma of TBI. Indeed, individuals with TBI or PTSD show significant overlap in symptoms resulting from emotional dysregulation including changes in mood and cognition, enhanced fear learning, and avoidance behaviours. These symptoms have been shown to be significantly worse in individuals with a comorbid diagnosis for TBI and PTSD compared to a diagnosis of TBI or PTSD alone, although the underlying mechanisms for this comorbidity are not well understood. The overlap in symptoms for TBI and PTSD can be explained by molecular changes that occur as a result of physical and/or emotional trauma in areas of the brain involved in emotion regulation. For example, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (involved in regulating the body’s stress response) in response to trauma can lead to maladaptive stress response and excess secretion of glucocorticoids. Heightened levels of glucocorticoids can subsequently result in increased release of glutamate in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (both areas involved in emotion regulation) which can be damaging to neurons and even cause cell death.

What’s new?

In one study, preclinical models have shown that TBI-induced trauma results in molecular changes in subcortical structures involved in emotion regulation behaviour such as the amygdala and hippocampus. Further mild TBI has been associated with decreased resting-state functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the insula. Studies using diffusion tensor imaging have shown that TBI and PTSD are both associated with white matter pathology which increases with the severity of TBI or PTSD. When looking at individuals with TBI, there is evidence of abnormalities in fronto-limbic white matter tracts (which connect the cingulate cortex to the hippocampus), while individuals with PTSD show decreased fractional anisotropy of the cingulum bundles. It is important to note, however, that TBI and PTSD were examined separately in the majority of this research. Even though worse outcomes are associated with comorbid diagnoses, structural and functional MRI studies that evaluate TBI and PTSD simultaneously are lacking. Nevertheless, the findings from these imaging studies show that white matter tracts that connect areas of the brain involved in emotion regulation are altered by both TBI and PTSD. This suggests that interventions that focus on emotion regulation may be particularly helpful for treating both conditions. In support of this, cognitive behavioural therapy, which focuses on improving emotion regulation, has been shown to be very effective in treating long-term comorbid PTSD and TBI.

What’s the bottom line?

Emotion dysregulation has an important role in the shared outcomes of TBI and PTSD. Early intervention with treatments like cognitive behavioural therapy that focus on improving emotion regulation may be helpful to minimize stress-induced molecular changes that occur following a traumatic event. In all, investigating the underlying changes in brain circuitry associated with TBI and PTSD through the lens of emotion regulation may be helpful for determining best practices for prevention and intervention when treating TBI and PTSD.

Weis et al. Emotion Dysregulation Following Trauma: Shared Neurocircuitry of Traumatic Brain Injury and Trauma-Related Psychiatric Disorders. Biological Psychiatry (2021). Access the original scientific publication here.