The Relationship Between the Menstrual Cycle and Sleep

Post by Shireen Parimoo

What is the menstrual cycle?

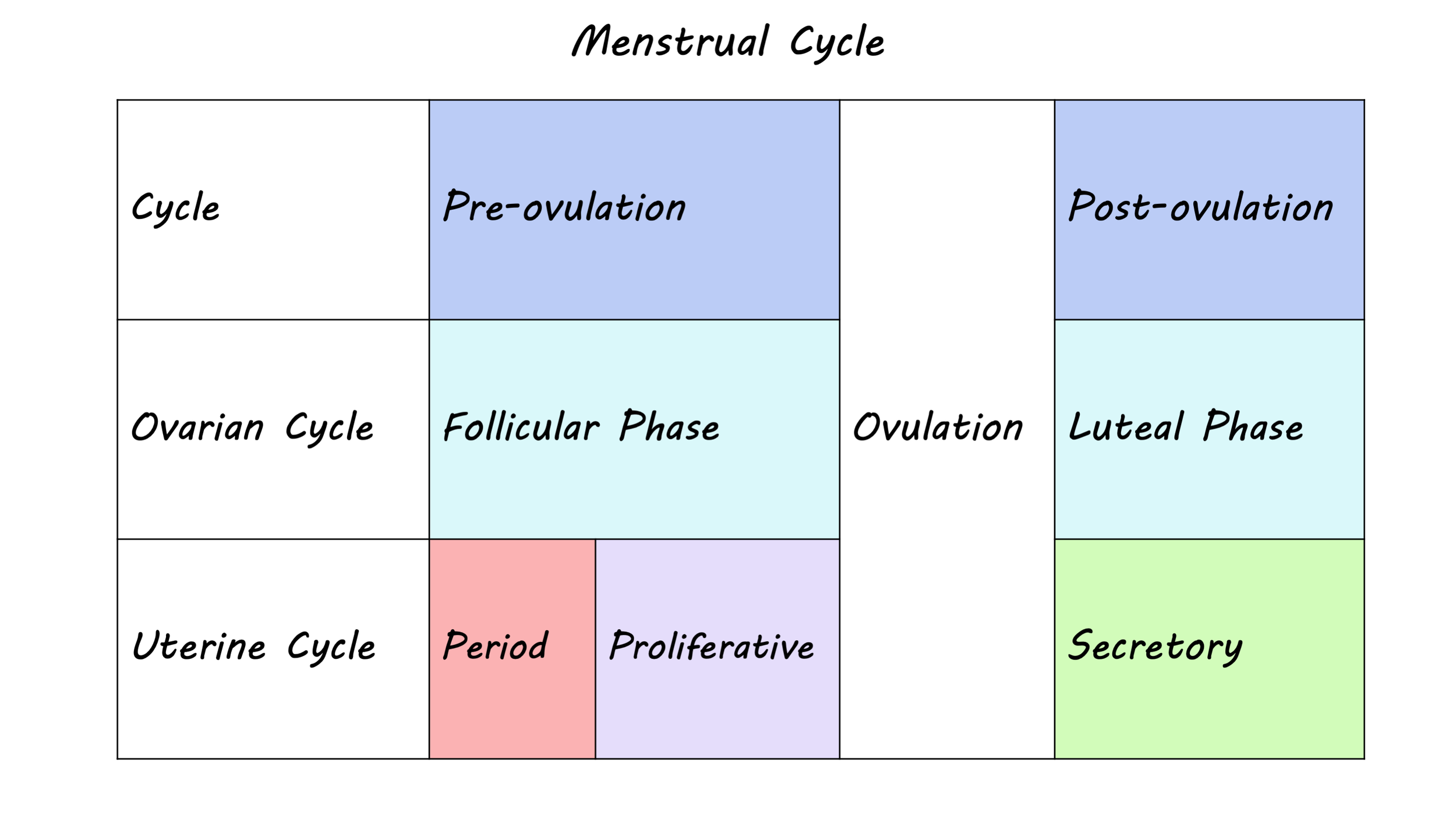

The menstrual cycle describes the fluctuation of ovarian hormones that typically occurs over a 28-day period, but can range anywhere from 21 to 38 days. The cycle is divided into two distinct phases: the follicular phase and the luteal phase. The follicular phase begins on the first day of menses - more commonly known as the period - which lasts between three to eight days. This phase ends with ovulation, when an egg is released from the ovary into the uterus, followed by the luteal phase, which lasts until the next menses.

In each phase of the menstrual cycle, hormonal changes result from an interaction between the brain and the reproductive system. In the follicular phase, follicle stimulating hormone released from the pituitary gland in the brain prepares the ovaries for ovulation and triggers the release of estrogens, which prepares the uterus for ovulation. Toward the end of the follicular phase, high levels of estrogens act on the brain to facilitate the release of luteinizing hormone, which in turn triggers ovulation. Once the egg is released, there is an increase in progesterone and estrogen but if pregnancy does not occur levels decline, leading to the next menses.

How does it affect sleep?

Sleep promotes physical and mental recovery, maintenance, and repair within the brain, and facilitates learning and memory. Thus, it is important to maintain a consistent sleep schedule and get good quality sleep, since sleep disturbances can not only interfere with day-to-day functioning and general well-being but can also disrupt cognitive performance and increase the risk of disease and dementia. Good sleep hygiene, such as keeping a consistent bedtime/nighttime routine, getting enough sunlight during the day, exercising regularly, and avoiding nicotine, alcohol, and stimulants in the evening can help. In general, women self-report more frequent sleep problems, increased daytime sleepiness, and poorer quality of sleep compared to men, yet objective measures like sleep duration suggest that women get more quality sleep than men.

Ovarian hormones partially contribute to these conflicting sex differences in objective and subjective measures of sleep quality. Across the female lifespan, the most pronounced hormonal changes take place during puberty, menses, pregnancy, and menopause, which coincide with sleep disturbances. During reproductive years, women experience more subtle fluctuations in their quality of sleep over the course of the menstrual cycle. Sleep disturbances are primarily observed during the luteal phase, partly due to elevated levels of estrogens and progesterone. For example, women report higher daytime sleepiness and more awakenings at night during the luteal compared to the follicular phase. Core body temperature at night is also elevated during the luteal phase, which is related to both hypersomnia (excessive sleep) and insomnia (inability to sleep). However, some objective measures of sleep quality such as total time spent sleeping and sleep efficiency are not consistently affected by the menstrual phase.

How is the brain involved?

Sleep consists of recurring cycles that usually last about 90 minutes, with one night of sleep involving between three to five sleep cycles. Each sleep cycle includes rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, when dreaming occurs, and non-REM sleep, which involves light and deep sleep. Polysomnography studies show that the duration of REM sleep is lower during the luteal phase than the follicular phase, whereas the duration of non-REM sleep becomes longer.

Ovarian hormones are increasingly being recognized for their relevance in non-reproductive functions through their impact on the brain. For example, there is evidence of better memory after a nap for women in the luteal phase compared to those in the follicular phase of their menstrual cycle. Estrogens and progesterone, which are elevated during the luteal phase, act on receptors in the hippocampus and the frontal cortex, regions that are involved in learning, memory, and decision-making. Moreover, these hormones have also been shown to have neuroprotective effects on the brain’s structure across the lifespan.

Slow-wave sleep (deep sleep) and sleep spindles are prominent features of non-REM sleep, which is when much of the sleep-related recovery and memory consolidation takes place. Sleep spindles refer to bursts of oscillatory activity (11-16 Hz) that typically occur during stage 2 of non-REM sleep. Notably, sleep spindles occur more frequently during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and are associated with memory performance. Higher levels of progesterone are thought to modulate spindle activity by acting on GABA receptors in the brain. Conversely, slow-wave sleep is characterized by low frequency oscillatory activity (0.5-3 Hz) and is reduced during the luteal phase. However, it is currently unclear how brain activity during different sleep stages is linked to specific phases of the menstrual cycle. More research is needed to better understand the complex and interdependent relationship between the female reproductive system and brain in relation to sleep and cognition.

References

Alonso et al. Sex and menstrual phase influences on sleep and memory. Current Sleep Medicine Reports (2021).

Baker & Driver. Self-reported sleep across the menstrual cycle in young, healthy women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research (2004).

Bixler et al. Women sleep objectively better than men and the sleep of young women is more resilient to external stressors: the effects of age and menopause. Journal of Sleep Research (2009).

Brann et al. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions of estrogen: basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Steroids (2007).

Brinton et al. Progesterone receptors: form and function in the brain. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology (2008).

Brown & Gervais. Role of ovarian hormones in the modulation of sleep in females across the adult lifespan. Endocrinology (2020).

Dorsey et al. Neurobiological and hormonal mechanisms regulating women’s sleep. Frontiers in Neuroscience (2021).

Driver et al. The menstrual cycle effects on sleep. Sleep Medicine Clinics (2008).

Genzel et al. Sex and modulatory menstrual cycle effects on sleep related memory consolidation. Psychoneuroendocrinology (2012).

Gervais et al. Ovarian hormones, sleep and cognition across the adult female lifespan: an integrated perspective. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology (2017).

Johnson et al. Epidemiology of DSM-IV insomnia in adolescence: lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and an emergent gender difference. Pediatrics (2006).

Mong & Cusmano. Sex differences in sleep: impact of biological sex and sex steroids. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B (2016).

Plante & Goldstein. Medoxyprogesterone acetate is associated with increased sleep spindles during non-rapid eye movement sleep in women referred for polysomnography. Psychoneuroendocrinology (2013).

Romans et al. Sleep quality and the menstrual cycle. Sleep Medicine (2015).

Schumacher et al. Progesterone: therapeutic opportunities for neuroprotection and myelin repair. Pharmacology and Therapeutics (2007).

De Zambotti et al. Menstrual cycle-related variation in physiological sleep in women in the early menopausal transition. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (2015).