Expectations of Reward and Efficacy Guide Cognitive Control Allocation

Post by Andrew Vo

What's the science?

Each day, we are faced with tasks and challenges for which we must decide whether the mental effort (in the form of cognitive control) to invest is worthwhile. The Expected Value of Control theory posits that people adjust the amount of mental effort they invest in a task by integrating information about the expected reward (the expected outcome) and the efficacy of task performance (the likelihood that investing effort will yield the desired outcome) to determine the expected value of control. The role of reward expectancy in shaping cognitive control is well-established, however, the effects and neural mechanisms of efficacy are far less studied. This week in Nature Communications, Frömer and colleagues investigated the contributions of reward, efficacy, and their interaction on behavioral and neural measures of control allocation.

How did they do it?

Across three studies, the authors tested their hypothesis that the allocation of cognitive control is based on the expected value of control. The worth of executing different types and amounts of control is determined by weighing its costs (i.e., mental effort) against its benefits. These benefits are shaped by a combination of the two incentive components: reward and efficacy.

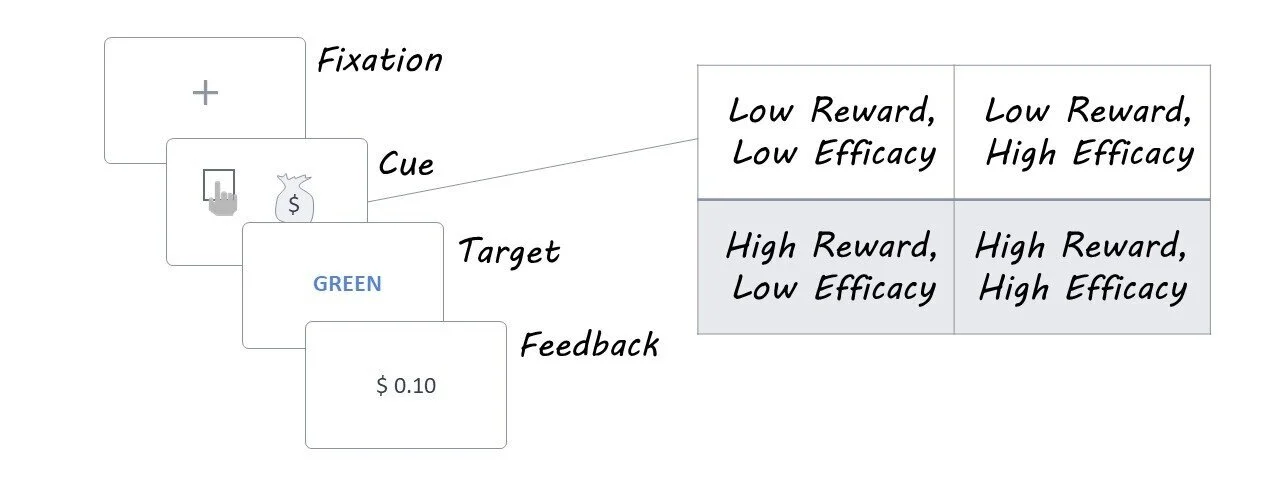

Participants completed a modified version of the color-word Stroop task that dissociated reward and efficacy effects on control allocation. On each trial, participants were initially presented with an incentive cue that disclosed whether they would receive a high or low monetary reward if successful ($0.10 vs. $1.00) and whether their efforts would be high or low in efficacy (success determined by their performance versus by the flip of a coin). They were then shown a Stroop stimulus — a color-word printed in either the same (congruent) or different (incongruent) color — to which they needed to respond with the color the word was written in rather than the word itself. Feedback was then given to indicate the value of the reward received. Correct reaction times (i.e., how fast the participant made a correct response) were used as a measure of task performance.

In Study 2, participants performed the task as their brain activity was recorded using EEG. The authors were interested in how reward and efficacy modulated the magnitude of two specific event-related potentials (ERP): the P3b (250-550 ms after cue onset that reflects incentive evaluation) and the CNV (500 ms before Stroop target onset that reflects control allocation).

What did they find?

The authors found that both reward and efficacy, as well as their interaction, modulated task performance. Participants were faster to make a correct response for higher levels of reward and efficacy. This pattern of findings was consistent whether each incentive component was varied in a binary manner (Study 1 and 2) or parametrically across four levels (Study 3). Control analyses ruled out that these effects were not simply due to speed-accuracy trade-offs, task difficulty, or practice effects.

EEG recordings (Study 2) revealed that reward and efficacy manipulations modulated the amplitude of both ERPs of interest. The P3b and CNV amplitudes were significantly larger in response to cues signaling larger rewards and efficacy. Notably, only the CNV was sensitive to the interaction of both incentive components. Examining trial-by-trial variability, the authors found that larger amplitudes in both ERPs were associated with an increased likelihood of correct responses and faster correct reaction times, with a more pronounced effect in CNV than P3b.

What's the impact?

This study provides behavioral and neural evidence supporting the critical roles of both reward expectancy and efficacy in determining the value of exerting cognitive control. The results are in line with predictions made by the EVC theory, which suggests that the integration of both incentive components (reward and efficacy) shapes how mental effort is allocated. As the authors succinctly state, “Cognitive control is critical but also costly”. This study illustrates how we may go about computing the worth of investing mental effort (in the form of cognitive control) towards achieving goals throughout our daily lives.

Frömer et al. Expectations of reward and efficacy guide cognitive control allocation. Nature Communications (2021). Access the original scientific publication here.