How Does Physical Overtraining Affect the Brain?

Post by Shireen Parimoo

What is overtraining?

Every athlete, whether elite or recreational, strives to perform at their best. Behind every touchdown, race, or personal best is a dedicated training regimen. For example, marathon runners progressively increase their mileage week after week, with a mix of intense and easy training days. In the final “tapering” week before a race, they reduce the frequency and intensity (i.e. training load) of their running. The idea is to give the body enough time to recover from all the cumulative training in the weeks prior for optimal performance by race day.

Excessive exercise over a long period of time can lead to overtraining syndrome when there isn’t sufficient opportunity for recovery in between bouts of exercise. In addition to rest and recovery, adequate sleep, nutrition, and cross-training are also important for preventing overtraining. Functional overreaching is a common acute response to a high training load. At this stage, athletes tend to be fatigued from their training and feel like they need to exert more effort than usual to perform at their standard level. When the training load is reduced, the negative effects of functional overreaching on performance disappear within a week or so. In fact, athletes commonly experience a boost in their performance afterward, called “supercompensation”, which might explain the importance of tapering the week before a marathon.

What are the symptoms of overtraining?

Overtraining affects anywhere from 5-60% of professional athletes. If proper recovery is not built into a training regimen, then the effects of overreaching can persist and start to have a long-term impact not only on performance, but also on mood, lifestyle, and the brain. Some of the common symptoms include muscle soreness, fatigue, lowered immune response, depressive symptoms, cognitive problems like difficulty concentrating, and sleep issues.

There are three stages of overreaching and overtraining, with each stage becoming progressively worse and longer-lasting:

non-functional overreaching: increased stress, fatigue, and muscle soreness along with poor sleep quality. Most of the time, this can be overcome by reducing training intensity and frequency and ensuring adequate sleep (1-3 weeks).

sympathetic overtraining: further changes in fitness such as increased heart rate and muscular weakness, as well as higher cortisol levels and hormonal changes due to the prolonged stress (1-3 months). This is mostly observed in endurance athletes like long-distance runners.

overtraining syndrome: a prolonged version of overtraining that can seriously alter the brain’s stress response and impact physical and mental health (6-12+ months).

How does regular exercise affect the brain?

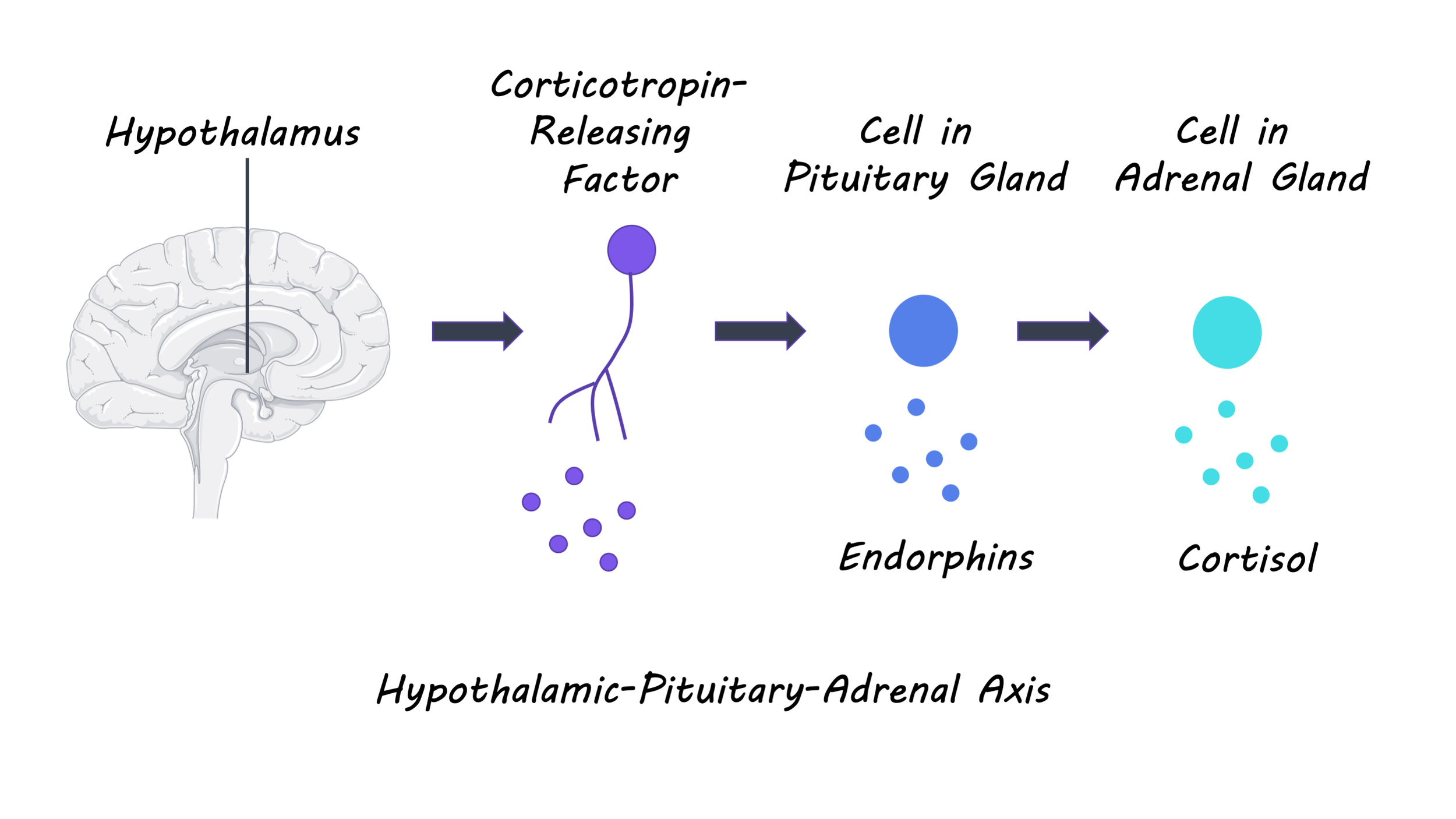

Neurotransmitter and hormonal imbalance contribute to overtraining. One way to think about overtraining is as a prolonged stress response to excessive exercise. Normally, the body’s stress response is regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. When a stressful event (i.e. an intense workout) occurs, noradrenaline levels increase and stimulate the hypothalamus in the brain. The hypothalamus releases the corticotropin-releasing factor, which stimulates the pituitary gland and also leads to increased heart rate. The pituitary gland then releases the adrenocorticotropic hormone, which stimulates the adrenal gland to produce the stress hormone cortisol. Cortisol suppresses the body’s immune response and triggers the “fight or flight” response by increasing blood glucose levels and heart rate. After a few hours, the cortisol circulating in the bloodstream inhibits the hypothalamus, terminating the stress response. Regular exercise helps the body adapt to physical stress and leads to decreased cortisol levels in response to future stressors. Importantly, this adaptation happens during the rest and recovery period. Exercise also increases serotonin levels in the brain and improves our sense of well-being. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that affects mood, appetite, cognition, and sleep, among other important functions. Serotonin also regulates the stress response by acting on the HPA axis.

How does overtraining affect the brain?

There is little opportunity for adaptation in between bouts of exercise without recovery periods, and excessive serotonin production might further contribute to HPA axis dysfunction. With overtraining, the body remains in a chronically activated stress response state that, in the long run, can lead to changes in the structure and function of various brain regions. Though research on the effects of overtraining on the brain and cognitive functions is somewhat scarce, there is ample evidence showing that a chronically activated stress response leads to changes in the brain. For example, prefrontal areas that help us with decision-making start to change in size and have different activation patterns in chronically stressed individuals. These individuals also start to rely on automatic rather than more effortful or strategic decision-making processes.

A recent study showed that excessive training affects decision-making processes. Endurance athletes completed an overreaching or normal training phase for three weeks. They were then brought into the lab to perform a reward-based decision-making task while undergoing an fMRI scan. The overreached athletes tended to choose smaller but immediate rewards over bigger rewards in the future, and they showed reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex when making decisions. Even though the authors could not – for ethical reasons – overtrain the athletes, this study provides an exciting avenue for future research on how overtraining affects brain functioning and cognition, which has several practical implications. Not only will it improve our understanding of how overtraining might impact the important day-to-day decisions of athletes, but this knowledge can be used to inform training plans that help ensure athletes get adequate rest and nutrition.

References

Armstrong & VanHeest. The unknown mechanism of the overtraining syndrome. Sports Medicine (2002). Access the original scientific publication here.

Cadegiani. Classical understanding of overtraining syndrome. In Overtraining Syndrome in Athletes (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.

Fulford & Harbuz. Chapter 1.3 – An introduction to the HPA axis. Techniques in the Behavioral and Neural Sciences (2005). Access the original scientific publication here.

Heisler et al. Serotonin activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis via serotonin 2C receptor stimulation. Journal of Neuroscience (2007). Access the original scientific publication here.

Kreher & Schwartz. Overtraining syndrome – A practical guide. Sports Health (2012). Access the original scientific publication here.

Lin & Kuo. Exercise benefits brain function: The monoamine connection. Brain Science (2013). Access the original scientific publication here.

Meeusen et al. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: Joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science (ECSS) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). European Journal of Sport Science (2013). Access the original scientific publication here.

Portugal et al. Neuroscience of exercise: From neurobiology mechanisms to mental health. Neuropsychobiology (2013). Access the original scientific publication here.

Soares et al. Stress-induced changes in human decision-making are reversible. Translational Psychiatry (2012). Access the original scientific publication here.

Wolff et al. Chronic stress, executive functioning, and real-life self-control: An experience sampling study. Journal of Personality (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.