A Coronavirus Protein Crosses the Blood-Brain-Barrier in Mice

Post by Leigh Christopher

What's the science?

COVID-19 has been associated with a number of central nervous system (CNS) symptoms including the loss of taste and smell, headaches, impaired consciousness, and even stroke. One reason for these symptoms could be that the SARS-CoV-2 virus (i.e., the virus responsible for COVID-19) enters the brain and acts directly on the CNS. Another possibility is those immune molecules known as cytokines (inflammatory molecules) associated with the virus cross the blood-brain-barrier, resulting in CNS symptoms. Yet a third possibility is that the virus sheds various proteins, which then cross the blood-brain-barrier and enter the brain. This week in Nature Neuroscience, Rhea and colleagues test whether the SARS-CoV-2 spike 1 protein (S1) can cross the blood-brain-barrier in mice.

How did they do it?

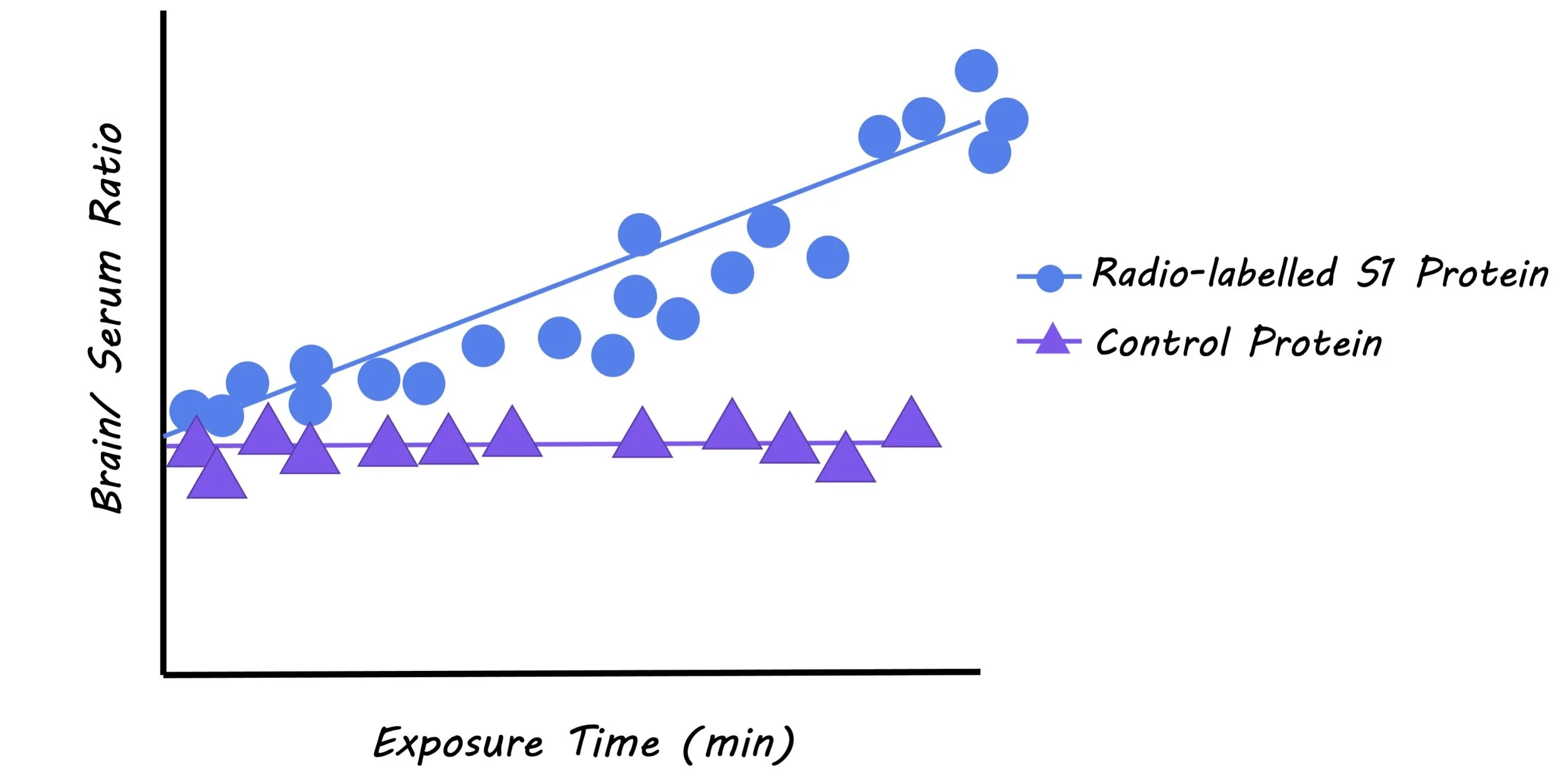

The authors radio-labelled S1 proteins from the SARS-CoV-2 virus, injected them intravenously into mice, and measured the blood-to-brain influx constant (a measure of the influx of S1 protein across the blood-brain-barriers). They did this using a method called multiple time regression analysis which allows for the measurement of protein influx to the brain while correcting for clearance of the protein out of the brain over time. They co-injected another radio-labelled protein along with the S1 protein that is known to have poor brain uptake, as a reference for how much S1 was crossing the blood-brain-barrier into the brain. The authors tested whether the S1 protein cleared the brain and entered other peripheral tissues and organs. A series of experiments were also performed to assess the mechanism of transport of the S1 protein across the blood-brain-barrier and into other tissues.

What did they find?

Radio-labelled S1 protein influx levels were significantly higher than the control protein, demonstrating that S1 does pass through the blood-brain-barrier and into the brain. They found that the virus entered a number of brain regions, and was also cleared from the brain through the blood, entering peripheral tissues, including the liver, kidney, and spleen. The authors attempted to understand the mechanism through which the S1 protein was transported across the blood-brain-barrier and into other tissues. When investigating the mechanism of transport of S1, they found evidence of blood-brain-barrier passage through adsorptive transcytosis, a mechanism where molecules bind to glycoproteins on endothelial cells and enter the brain through vesicle transport.

SARS-CoV-2 is thought to enter cells by binding to a protein called ACE2. The authors found that co-injection of ACE2 and radio-labelled S1 protein increased the influx of S1 protein into the brain and lungs, suggesting that S1 uptake into these tissues was mediated by ACE2. They also found strong evidence of the involvement of other receptors. Next, the authors wanted to assess whether S1 uptake is increased during an inflammatory state, which is typically induced by the virus. Upon injection of lipopolysaccharide (a substance inducing an inflammatory state), the influx of S1 protein to the lungs (via adsorptive transcytosis) was higher, and the influx of S1 protein to the brain was also higher (via blood-brain-barrier disruption). These findings suggest that inflammation further increases S1 protein entry into the brain and lungs.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to show that the S1 protein of SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood-brain-barrier and enters the brain in mice. This research sheds light on the potential mechanisms by which the S1 protein enters the brain and other tissues. Further understanding the mechanism of uptake, and whether the virus itself can also pass into the brain will be an important question for future research. As this study was performed in mice, it will also be crucial to investigate whether S1 passes through the blood-brain-barrier in humans.

Rhea et al. The S1 protein of SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood–brain barrier in mice. Nature Neuroscience (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.