Uncovering Proteins That Interact with a Disease Form of Tau

Post by D. Chloe Chung

What's the science?

Tau is a microtubule-binding protein that normally contributes to the stability of the central nervous system. In multiple neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, tau becomes abnormally phosphorylated and detaches from microtubules, leading to synaptic dysfunctions and neuronal death. Many studies have investigated the exact mechanisms of how tau phosphorylation contributes to the disease course, but there is a gap in knowledge of what types of proteins interact with phosphorylated tau (pTau). This week in Brain, Drummond, Pires, and colleagues use complementary proteomics approaches to discover previously unknown protein interactors of pTau.

How did they do it?

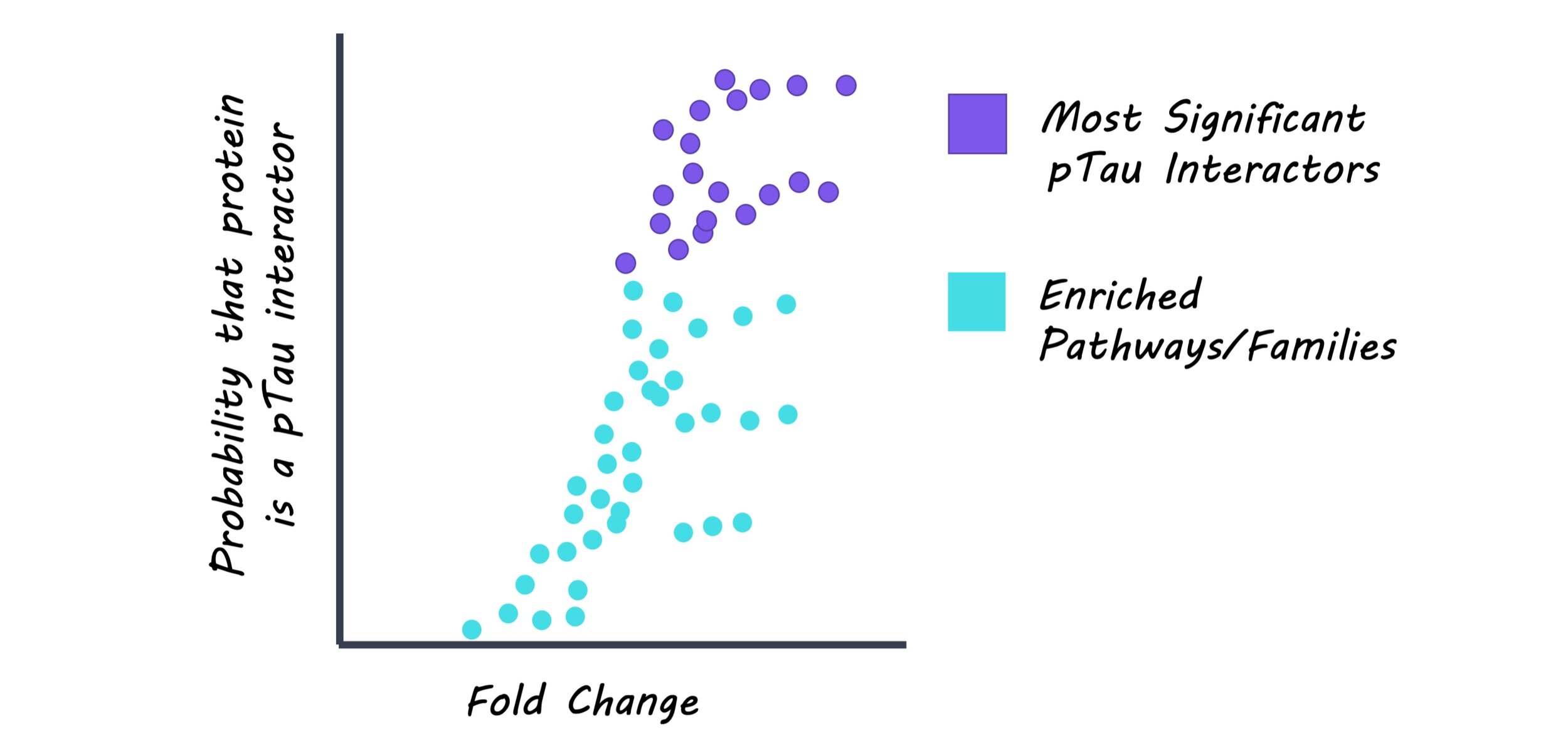

Neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), composed of pTau, were dissected and isolated from brain samples of Alzheimer’s disease patients using a laser-capture microdissection technique. These samples were analyzed to identify proteins other than pTau that are present in NFTs. pTau was extracted along with its protein interactors from the Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. Here, an antibody that can detect a specific phosphorylation site on tau was used to isolate the pTau-interactor complex. Using these samples, the profile of pTau and its interacting proteins was compared to the list of NFT-associated proteins. Also, pTau-interacting proteins were categorized based on related biological pathways or protein families to better understand which biological aspects are closely related to pTau.

What did they find?

From the first proteomics analysis, the authors found 542 proteins to be present in NFTs, including tau and other proteins that have been well-documented for their association with NFTs. From the second proteomics analysis, the authors found 125 proteins that interact with pTau. Interestingly, many of pTau interactors were associated with two major protein degradation pathways: one involved ubiquitin that tags proteins to be degraded by proteasomes, and the other involved lysosomes that break down proteins with digestive enzymes. These findings suggest an important pathological link between pTau and impaired protein degradation, which has been largely hypothesized in the field. Importantly, the authors compared two proteomics datasets and found that 75 out of 125 pTau-interacting proteins were also present in NFTs. Among them, 12 proteins have never been reported to interact with pTau before, meaning that the authors found new pTau-interacting proteins from their analysis. The type of these new pTau interactors varied, ranging from proteins that bind to DNA or RNA to subunits of enzymes or ribosomes.

What’s the impact?

While there have been several studies that have reported protein interactors of tau, this study is the first to find proteins that interact specifically with phosphorylated Tau in the human brain. In particular, this work identified novel proteins that have never been reported to be associated with tau before, opening new areas to investigate tau biology. Findings from this study will elevate our understanding of how tau exerts its toxic effects in the brain upon phosphorylation. Also, this study will be useful in identifying potential drug targets to treat Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases in which tau is abnormally phosphorylated.

Drummond, Pires et al. Phosphorylated tau interactome in the human Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.