Replay of Spatial Paths in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex Facilitates Strategy Shifting

Post by Cody Walters

What’s the science?

Planning and decision-making often require remembering specific routes and locations. The hippocampus and prefrontal cortex have been shown to replay task-relevant spatial trajectories following learning, and this reactivation of behavioral sequences has been viewed as a possible neural mechanism for memory consolidation and retrieval. However, how hippocampal and prefrontal cortex replay relate to one another and whether they play dissociable roles in learning and memory remains unclear. This month in Neuron, Kaefer et al. identified novel properties of prefrontal replay in rats navigating a rule switching task.

How did they do it?

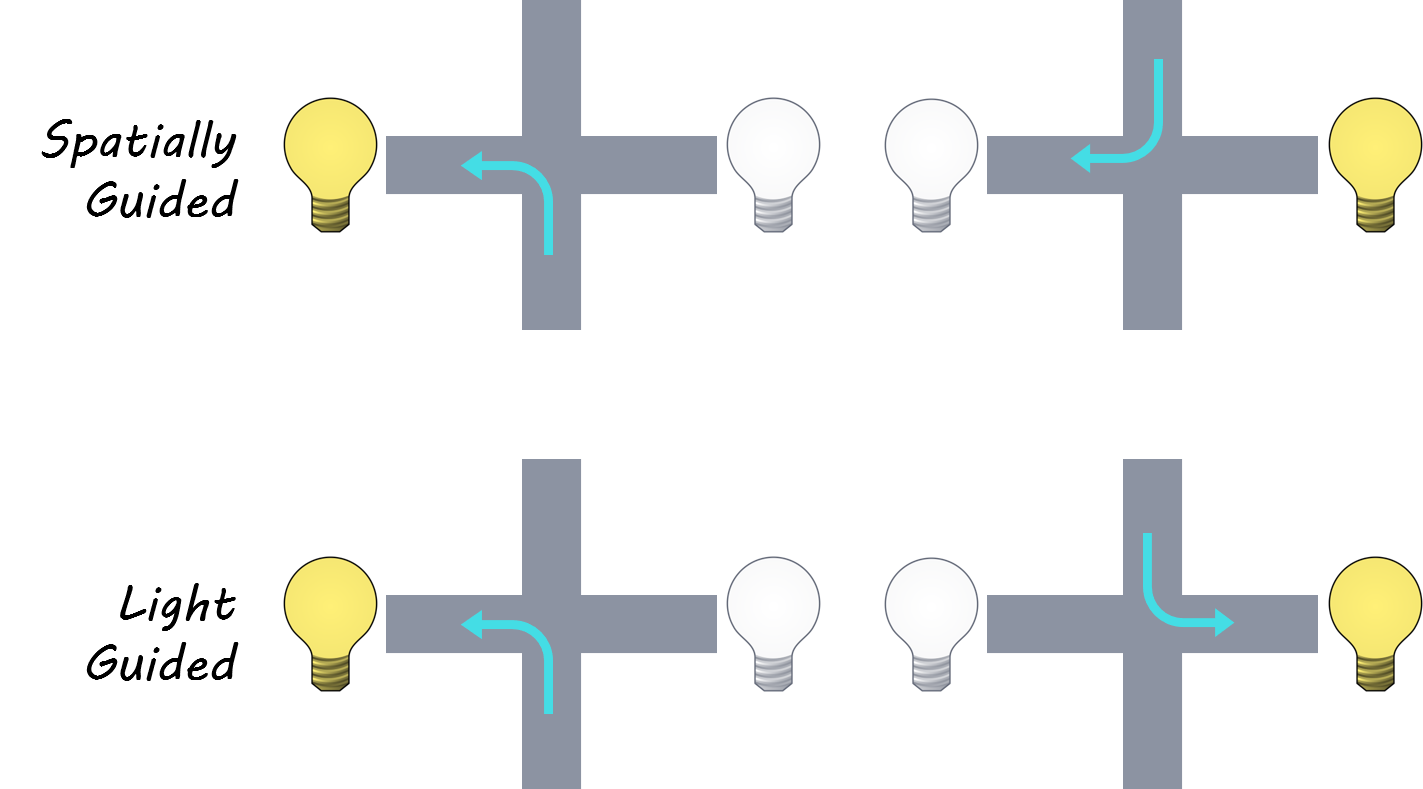

The authors trained four rats to perform a rule switching task on a plus maze (a maze with four arms, shaped like a plus sign). Rats were placed at the end of either the north or south arm and then had to navigate to either the east or west arm to receive a food reward. Importantly, there were two rules: under the spatial rule, one of the two horizontal arms was consistently rewarded, while under the visual rule rats had to go to the arm that had a light cue to receive food. Each session started off with one of the two rules in play until the animal reached a set performance criterion, at which point there would be an unannounced rule switch. They recorded neural activity from the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the dorsal hippocampus (HPC) of the rats as they performed the task. This allowed the authors to explore the differences and similarities between how the HPC and mPFC encode information about space, replay spatial paths, and respond to rule changes.

What did they find?

They found that, unlike hippocampal place cells, most mPFC neurons had symmetrical spatial representations of the environment (e.g., an mPFC neuron that responded to the middle location on the north arm of the maze also responded to the middle location on the south arm of the maze). They also observed both forward (start arm to goal arm) and backward (goal arm to start arm) spatial trajectory replay in the mPFC. Importantly, these mPFC replay events did not significantly co-occur with HPC replay. At the goal location (where the rats received food), the rate of mPFC replay was positively correlated with rule switching performance (i.e., the number of laps it takes before shifting over to the correct strategy following a rule switch). On the other hand, the rate of HPC replay at the goal location was negatively correlated with rule switching performance. Interestingly, when rats were at the center of the plus maze (just prior to making a choice to either go left or right) there were more mPFC forward replays on error laps and more backward replays on correct laps (whereas the HPC exhibited an increase in both forward and backward replays on correct laps relative to error laps at the center of the maze).

What’s the impact?

Previous work has shown that mPFC task-relevant replay occurs during sleep, but this study suggests that mPFC replay 1) occurs in awake states, 2) facilitates behavioral flexibility in a dynamic environment, and 3) might be largely independent of HPC replay. These findings advance our understanding of how different networks respond to the challenge of shifting environmental contingencies and highlight replay as potentially being a more general neural computation with structure-specific function.

Kaefer et al. Replay of Behavioral Sequences in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex during Rule Switching. Neuron, (2020). Access the publication here.