Surprise and Decision Making in the Anterior Cingulate Cortex

Post by Anastasia Sares

What's the science?

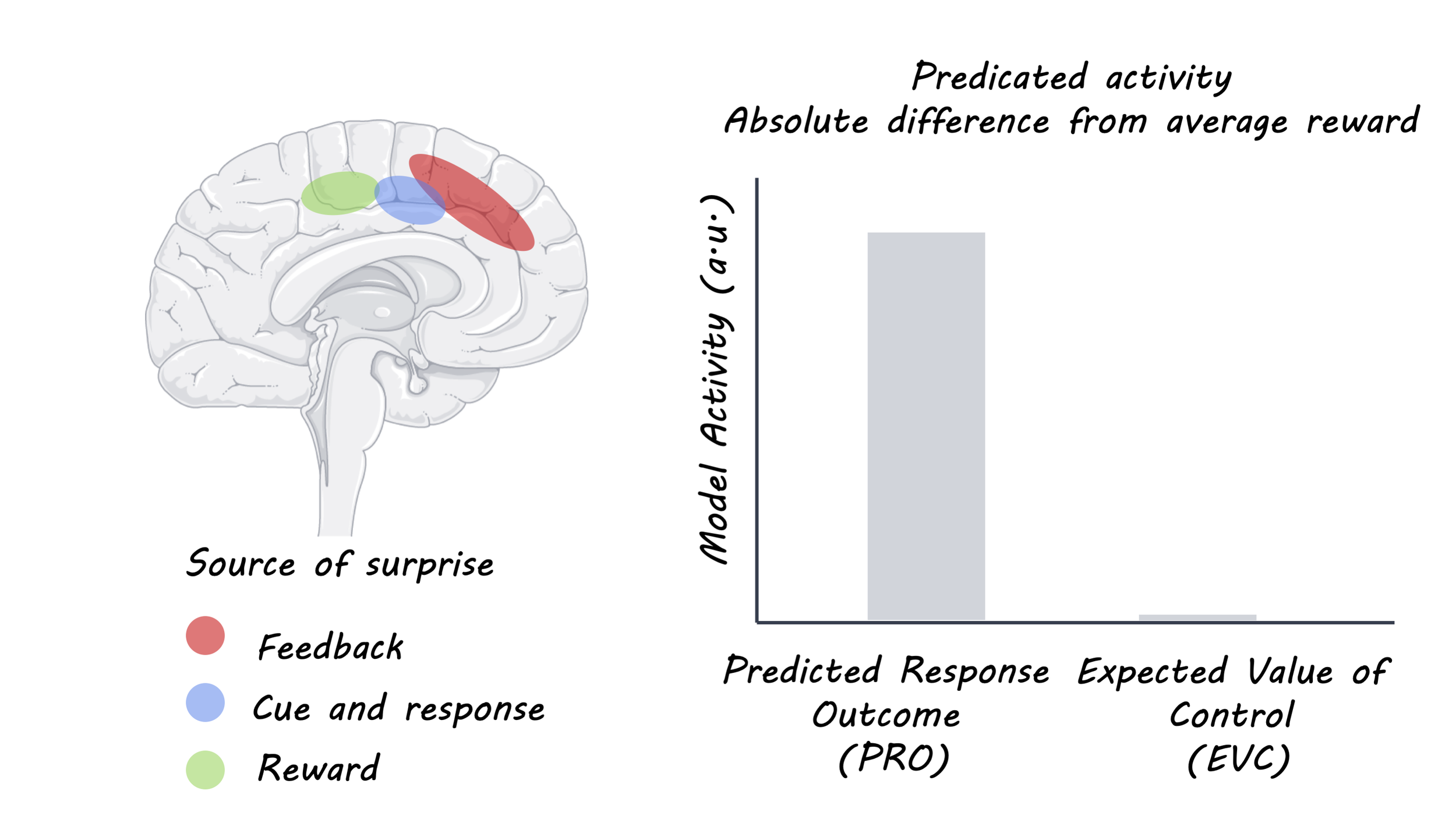

The anterior cingulate cortex, situated in the frontal lobe at the midline where the two hemispheres meet, is an important region of the human brain. Previous studies have connected it to error detection, cognitive control, and decision making. However, there are a few different hypotheses about what drives activity in this area. The “choice difficulty” hypothesis (CD) says that the anterior cingulate tracks difficulty—tougher decisions generate more activity. The “expected value of control” hypothesis (EVC) tracks net gain—how much reward will I get for the effort I put in? EVC predicts more activity for high reward, especially if the brain has to gear up and make an effort in order to get the reward. Finally, the “predicted response outcome” hypothesis (PRO) tracks surprise—events that violate expectations generate more activity, regardless of whether the results are perceived as “good” or “bad.” This week in Nature Human Behaviour, Vassena and colleagues pitted these three hypotheses of anterior cingulate function against each other in a speeded decision-making task.

How did they do it?

Before they started the experiment, participants learned to associate random fractal images with a certain number of points (picture 1 = 30 points, picture 2 = 80 points, etc.). They were told that the points they accumulated in the task would translate into extra money at the end of the experiment. In each trial of the task, four of the fractal images were shown on the screen. The participants had three-quarters of a second to choose either the set of images on the left or the set of images on the right. Of the images they chose, one would be randomly selected, and they would receive the equivalent amount of points. To complete this task, therefore, the participants had to be good at quickly estimating the value of the options on the right versus the options on the left. The task was completed in MRI so the response of the anterior cingulate could be measured.

Each of the hypotheses presented earlier (choice difficulty, expected value of control, and predicted response outcome) should show a different pattern of activity in the anterior cingulate during this task. CD predicts the most activity when the choice is difficult; that is when the amount of points on the left is similar to the amount on the right. EVC predicts the opposite: the anterior cingulate should be least active when the options are similar because the difference in potential reward is small compared to the effort required to distinguish between them. PRO predicts two peaks of activity, because with a large difference in value, one option is surprisingly bad, and with a small difference in value it is uncertain which option you will choose (making the choice itself “surprising”).

What did they find?

The authors compared the activity in the anterior cingulate cortex to the three different predictions and found that the PRO model (predicted response outcome) matched most closely. This is in line with the idea that the anterior cingulate reacts to unlikely or unpredicted events (surprise). During a task like this, people are quickly able to figure out how difficult the average trial is, so when a surprisingly bad option or two very similar options appear, the anterior cingulate’s activity increases. What’s more, an extremely low or high reward at the time of feedback also activated the same area.

What's the impact?

This study tested predictions from three different hypotheses and found one to be the clear winner: the main function of the anterior cingulate is processing surprise. This is a crucial step in the scientific enterprise; after some hypotheses are generated about the natural world, they must be tested against one another in carefully designed experiments that allow us to determine which hypothesis is stronger.

Vassena et al. Surprise, value and control in anterior cingulate cortex during speeded decision-making. Nature Human Behavior (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.