Synchronizing Brain Circuits Restores Working Memory in Older Adults

Post by Amanda McFarlan

What's the science?

Working memory is a type of short-term memory (important for immediate processing and integrating of an individual’s surroundings) that is known to decline with age. Theories of aging propose that decline in cognitive processes like working memory may be a result of desynchronization between cortical areas in the brain. Previous studies have shown that synchronization in the temporal cortex occurs during working memory tasks. This week in the Nature Neuroscience, Reinhart and colleagues investigated the role of temporal synchronization on working memory performance in aging.

How did they do it?

The authors recruited a total of 84 male and female participants (42 younger adults aged 20-29 years old and 42 older adults aged 60-76 years old) for their study. They used an experimental paradigm where the older adults participated in both the experimental and control conditions, while the younger adults only participated in the control condition. In the experimental condition, electroencephalography (EEG) activity and task performance levels were recorded during and after the administration of frontotemporal in-phase theta-tuned high-definition transcranial alternating-current stimulation (HD-tACS). In the control condition, the participants’ EEG activity and task performance levels were recorded during and after the administration of sham HD-tACS. Participants performed a working memory task and a control task while receiving HD-tACS. During the working memory task, participants were presented with an image of a real-world object that was followed by a delay. Then, they were presented with an image of another real-world object and had to determine whether this object was the same or different from the image they had previously been shown. For the control task, participants were presented with a real-world object, followed by a delay. Then, they were presented with a grated stimulus (see Figure) and they had to determine if the grating was titled clockwise or anti-clockwise. The participants alternated between the two tasks (working memory and control) 10 times during the administration of HD-tACS (total of 25 minutes) and 20 times in the post-stimulation period (total of 50 minutes).

What did they find?

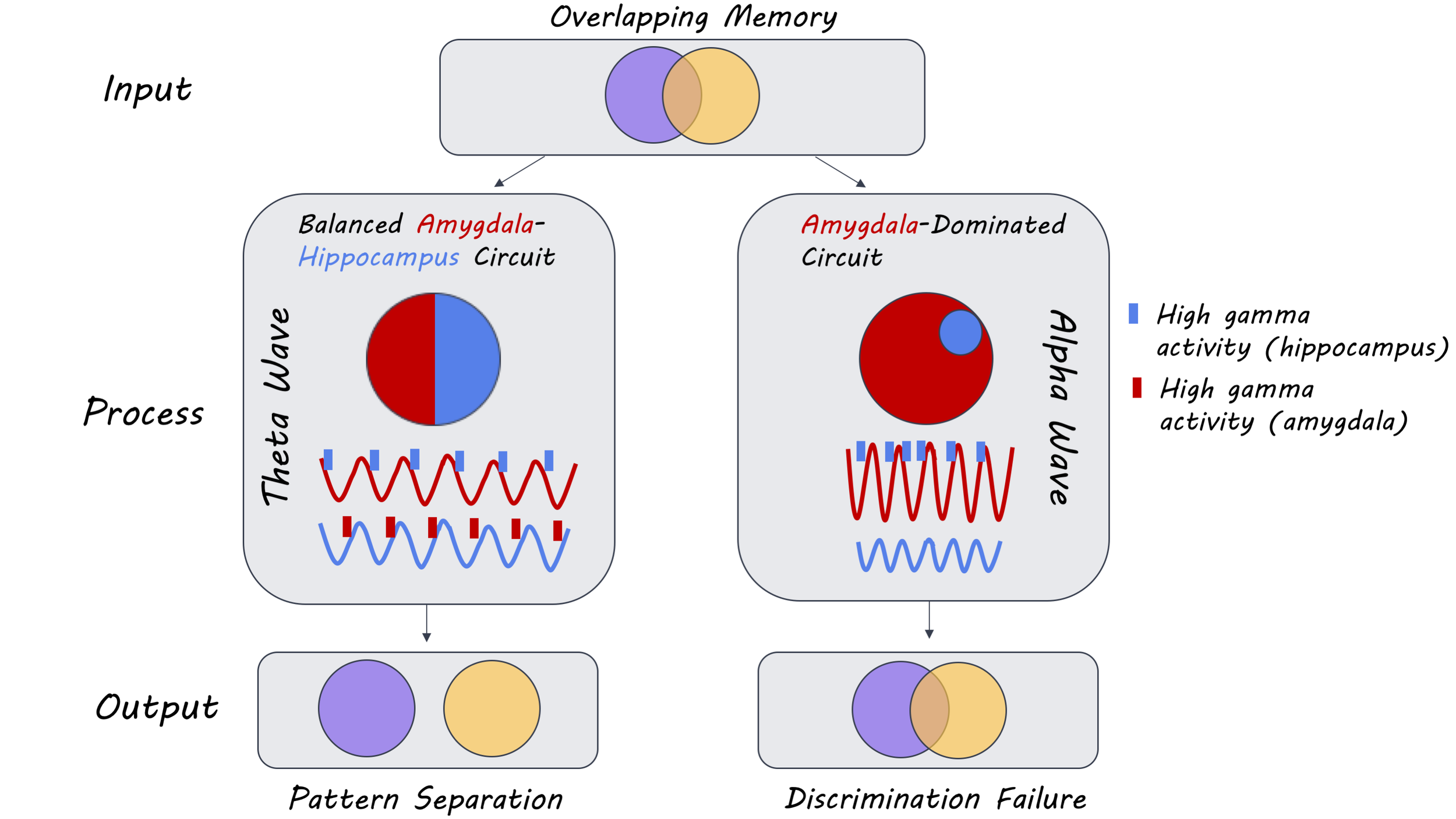

The authors found that the older adults in the control condition were slower and less accurate when performing the working memory task compared to the younger adults, suggesting that older adults display deficits in working memory performance. They showed that younger adults displayed increased memory-specific coupling of theta-gamma rhythms in the left temporal cortex, while older adults showed no evidence of brain activity coupling. These findings suggest that coupling of theta-gamma rhythms in the temporal cortex are important for working memory and may be predictive of behavioural success. Next, they determined that younger adults, but not older adults, had significantly increased phase synchronization between the prefrontal cortex and left temporal cortex during the working memory task compared to the control task. However, they determined that there were no differences in synchronization between the temporal and occipital cortices between older and younger adults, suggesting that short-range communication between nearby sensory cortices remains intact in older adults, while long-range communication becomes less efficient. Next, the authors examined the effects of HD-tACS stimulation on working memory performance in older adults. They found that HD-tACS stimulation improved working memory performance in older adults to levels that were comparable to younger adults and that these effects were long-lasting. Additionally, HD-tACS stimulation increased theta-gamma coupling as well as increased theta-phased synchronization between the prefrontal and left temporal cortices during the working memory task, similar to younger adults. Together, these findings suggest that HD-tACS stimulation is sufficient to induce temporal synchronization in brain activity that improves working memory performance.

What's the impact?

This is the first study to show that cognitive decline may be a result of desynchronization between long-range frontotemporal connections. Importantly, the authors showed that stimulation with high-definition transcranial alternating-current is sufficient to improve deficits in working memory in older adults to levels that are indistinguishable from younger adults. Altogether, these findings highlight a non-invasive, non-pharmacological intervention that may be useful for treating and improving cognitive decline in aging or clinical populations.

Reinhart and Nguyen. Working memory revived in older adults by synchronizing rhythmic brain circuits. Nature Neuroscience (2019). Access the original scientific publication here.