Hippocampus-Amygdala Communication Supports Pattern Separation of Emotional Memories

Post by Shireen Parimoo

What's the science?

Pattern separation is a hippocampal-dependent process that allows us to discriminate between similar events or experiences - like remembering where we parked the car at work on a specific day. Emotional events are remembered vividly because they increase arousal, which enhances memory formation and retrieval. The strength of emotional memories is modulated by the amygdala. Memories for emotional events are often biased to central aspects of the event while peripheral details are forgotten, making it difficult to discriminate between similar emotional events. The precise neural mechanism supporting this process remains unclear. This week in Neuron, Zheng and colleagues investigated the neural mechanism underlying the pattern separation of emotional memories in the amygdala and hippocampus using intracranial recordings.

How did they do it?

Seven pre-surgical epilepsy patients completed an episodic memory task with emotional stimuli while local field potentials were recorded from the amygdala and the hippocampus using intracranial stereo-electroencephalography. The memory task consisted of two phases: (i) an encoding phase, in which participants had to rate the emotional valence of positive, negative, and neutral images, and (ii) a retrieval phase, in which they had to make old/new judgments about the same, novel, or perceptually similar (‘lure’) images. The lures were presented to create interference between previously presented target images and the novel lures. To examine pattern separation, the authors computed the oscillatory power (squared amplitude), phase synchrony (phase coupling strength of signals in different regions of the brain), and phase-amplitude coupling (coupling between the phase of one signal and the amplitude of another signal) in different frequency bands. To determine whether hippocampal oscillations were driving oscillatory activity in the amygdala or vice versa, they computed the phase-slope index and performed a Granger causality analysis. Finally, they trained a classifier using the occurring phases of high-frequency activity (HFA) relative to the theta (2-7 Hz) and alpha bands (7-14 Hz) as inputs to predict whether participants would false alarm or correctly reject the lures.

What did they find?

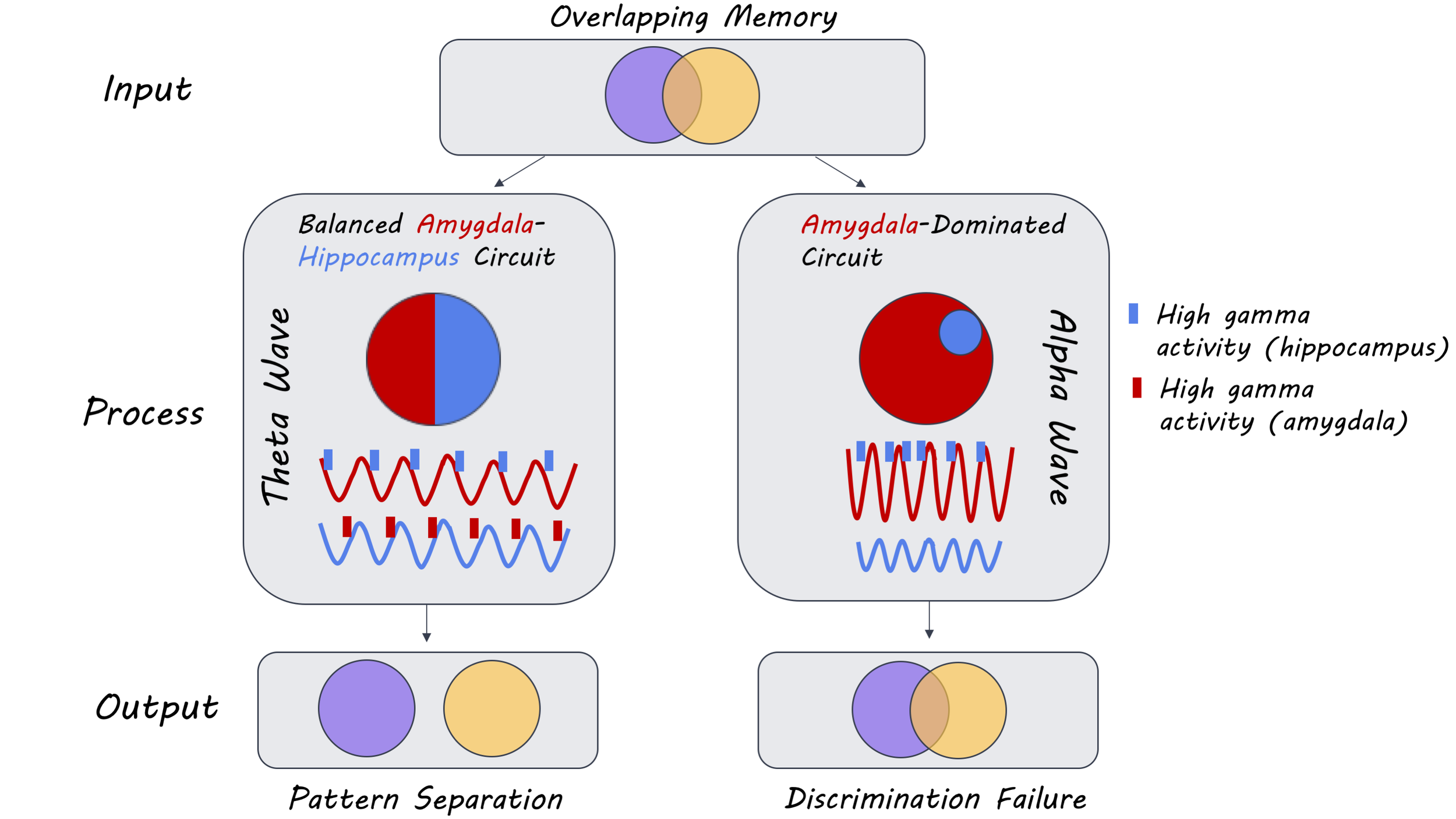

Participants performed well on the memory task with 80% accuracy overall. However, they were worse at discriminating emotional lures than neutral lures, with poorer discrimination of negatively-valenced lures than positive lures. Oscillatory activity was observed in the theta and alpha frequency bands when participants made recognition judgments. Specifically, in the hippocampus there was greater theta activity on trials where participants correctly identified the lure images as being new, which was accompanied by a simultaneous reduction in alpha power. In the amygdala, on the other hand, there was a lag between increased theta activity and a subsequent reduction in alpha power. Alpha activity increased on false alarm trials where participants incorrectly categorized images as being old. Oscillatory activity in the amygdala and the hippocampus was synchronized in the theta band on trials where the participant correctly identified a lure and in the alpha band on false alarm trials. This pattern of activity was present for both emotional and neutral images, but stronger for emotional images only on lure trials. This suggests that theta and alpha oscillations in the amygdala and hippocampus are involved in pattern separation, which is modulated by emotional valence.

Bidirectional communication between the hippocampus and the amygdala in the theta band was observed on correctly identified lure trials, and unidirectional communication was observed in the alpha band from the amygdala to the hippocampus on lure false alarm trials. Similarly, there was greater phase-amplitude coupling between theta oscillations in the amygdala and HFA in the hippocampus — as well as the reverse — on correctly identified lure trials. There was also a modulation of hippocampal HFA by alpha oscillations in the amygdala on lure false alarm trials. The trough of the theta cycle was associated with HFA in the amygdala (descending slope) and the hippocampus (ascending slope) on correctly identified lure trials. Such theta phase-dependent modulation of HFA was not present on lure false alarm trials. Moreover, the influence of amygdala theta oscillations on the hippocampus was stronger with emotional stimuli than neutral images, especially for negatively-valenced images. However, this emotional modulation of directional connectivity was not observed in the reverse direction (hippocampus to amygdala) or on lure false alarm trials. Thus, bidirectional communication between the amygdala and the hippocampus in the theta band results in the correct discrimination of lures from targets, whereas a disproportionately amygdala-driven interaction in the alpha band results in poor discrimination.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to show that bidirectional theta oscillations between the hippocampus and the amygdala at memory retrieval are necessary for the pattern separation of emotional events. These findings are consistent with the literature demonstrating the role of low-frequency oscillations in memory formation and provide further insight into the mechanism that allows for the resolution of interference between highly similar emotional events at retrieval.

Zheng et al. Multiplexing of theta and alpha rhythms in the amygdala-hippocampal circuit supports pattern separation of emotional information. Neuron (2019). Access the original scientific publication here.