How Exercise Protects Neurons from Aging and Alzheimer’s

Post by Anastasia Sares

What's the science?

A number of studies are showing that physical activity and brain health go hand in hand, especially where aging and Alzheimer’s are concerned. But how exactly does exercising our body affect our brain cells? This week in Neurobiology of Aging, Berchtold and colleagues identified a few key cellular functions influenced by aging that might be recoverable through physical activity.

How did they do it?

The authors examined human brains post-mortem. The participants were part of a large project and health data about them was already being recorded (like hours of weekly exercise, age, or cognitive status). When a person in the study passed away, the authors obtained a small sample of brain tissue from the hippocampus: an important structure involved in memory formation. They broke open the cells from each sample and used microarray technology to find out what genes were being expressed. A microarray chip has thousands of small wells that bind to specific molecules, so by looking at where molecules were binding to the chip, it was possible to see which genes were activated. or expressed.

Two completely independent sets of data: one data set had two groups differing on amount of exercise (high- vs low-exercise), and the second data set had three groups, one with young adults (20-59 years), one with normal aging adults (69-99 years), and one with Alzheimer’s disease (AD; 73-99 years). In the first data set, the authors looked for differences in gene expression that were significantly affected by exercise. In the second set, they looked for differences in expression affected either by age (comparing younger vs. older participants), or cognitive status (older normal aging vs Alzheimer’s). Finally, the authors combined the results and found genes that were affected by both exercise and aging: they called these “anti-aging/AD genes.”

What did they find?

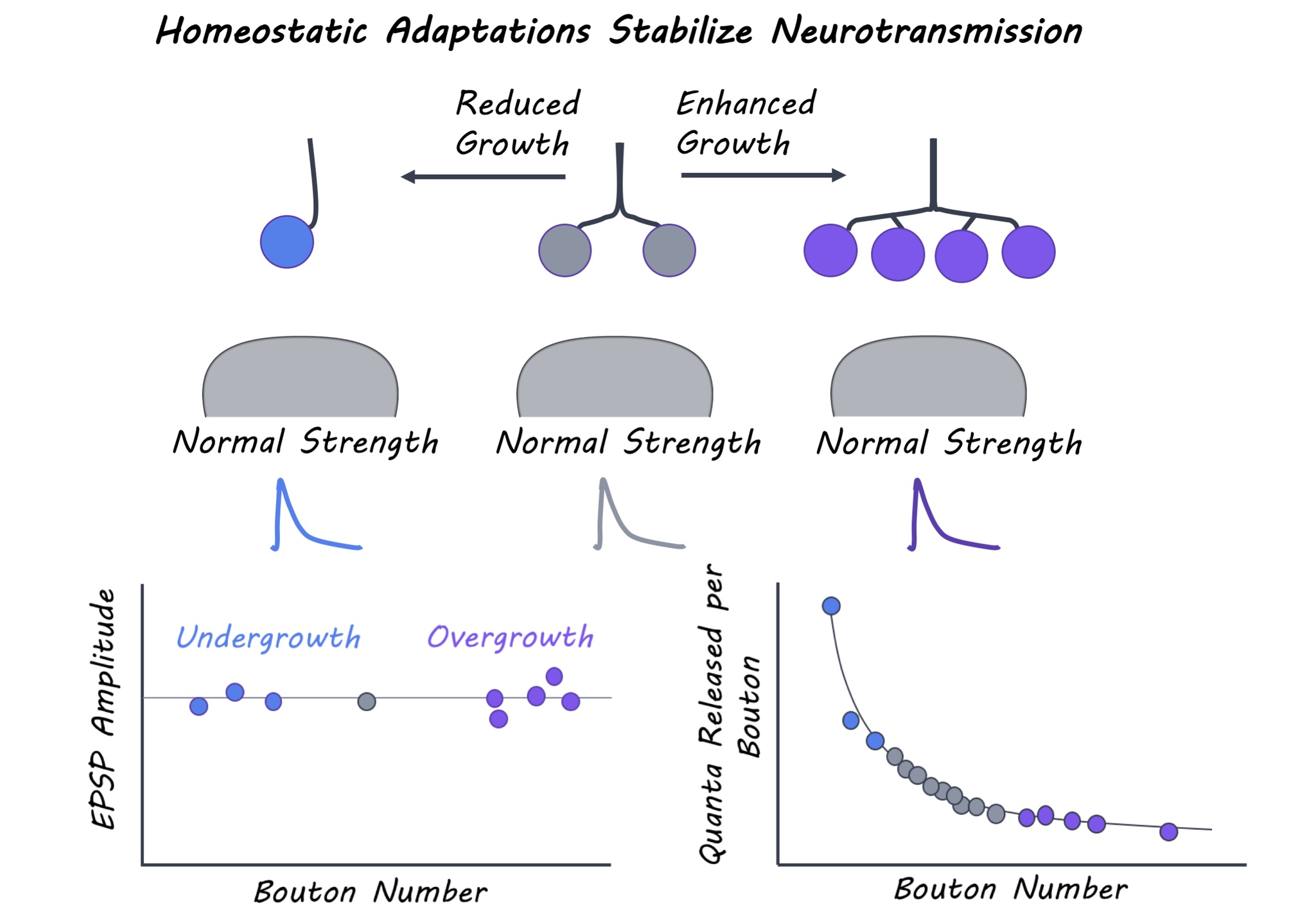

Of the overlapping genes, about 95% of the genes were affected in opposite ways by aging and exercise—70% of these genes showed declining expression with aging and increased expression with exercise. This suggests that exercise counteracts many of the effects of aging and Alzheimer’s. A large number of the genes were related to mitochondria: the structures inside a cell responsible for producing energy. Another group of genes were involved in communication between neurons at the synapse, where one neuron releases chemical messengers to be received by another. Other genes involved neuron infrastructure and plasticity.

What's the impact?

Energy production declines with age, even on the level of the cell. Exercise can keep neurons youthful, and it seems to do this by repairing gene expression, specifically for mitochondrial and synaptic functions. The authors’ use of independent datasets to verify their findings is an important research method that made their results more reliable.

Berchtold et al. Hippocampal gene expression patterns linked to late-life physical activity oppose age and AD-related transcriptional decline. Neurobiology of Aging (2019). Access the original scientific publication here.