Decreased Short-Range Brain Connections Linked to Social Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Post by Deborah Joye

What's the science?

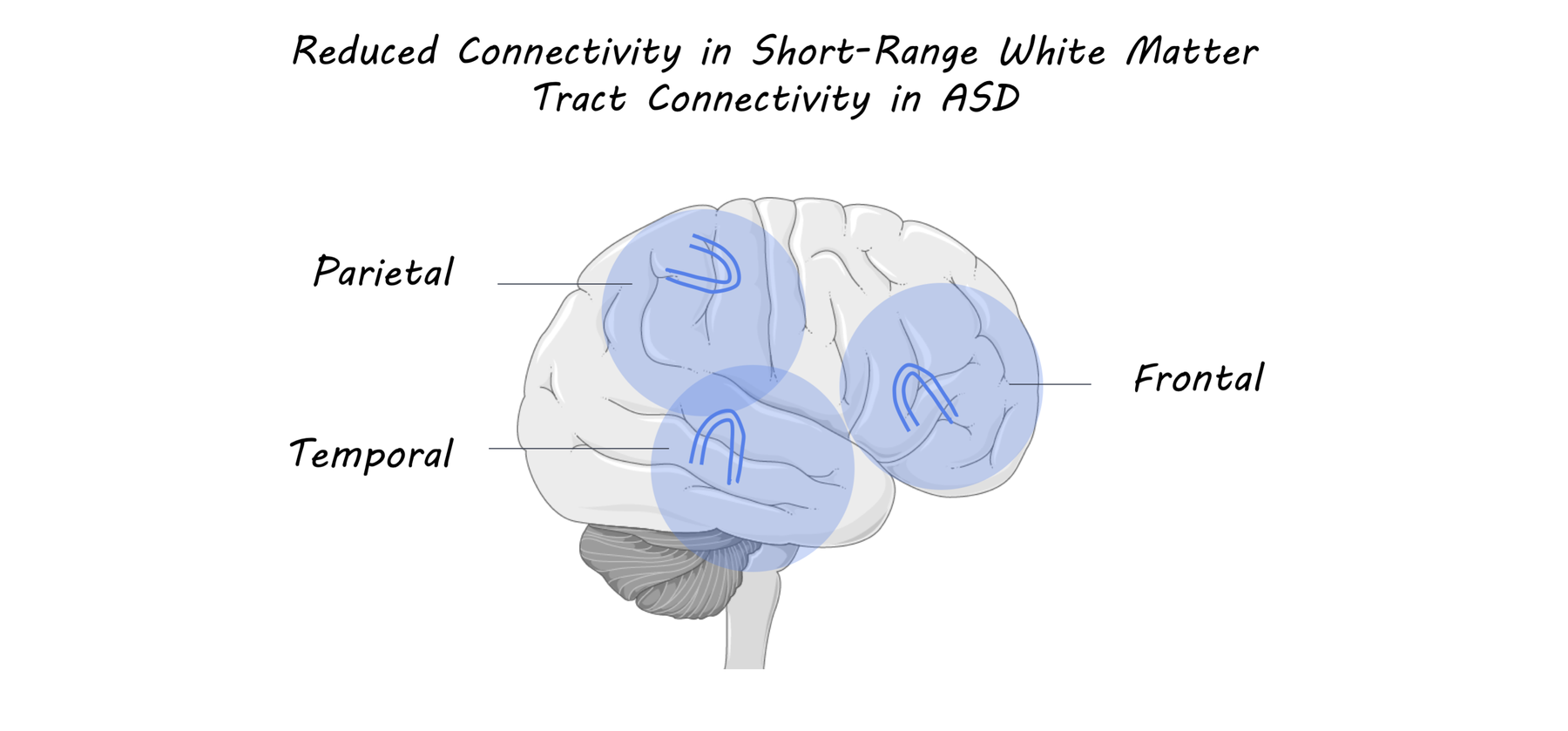

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodivergent condition that results in a range of symptoms including impaired social communication and restricted, repetitive behaviors. The brain can be broken down into local connections within brain regions, and long-range connections between more distant regions. Researchers have hypothesized that brain regions in individuals with ASD are more highly connected to themselves than with other more distant brain regions. Recent studies, however, have found that individuals with ASD can display reduced connectivity, overconnectivity, or a combination. Just under the surface of the cortex there are U-shaped connections between adjacent cortical gyri (the bumps of the brain). These superficial connections are the last to be myelinated in development, which makes them more adaptable to change. Whether these short-range connections are altered in ASD and how they may change throughout the lifespan remains unclear. This week in Brain, d’Albis and colleagues used brain imaging to investigate whether white matter tract connectivity in adults with high-functioning ASD correlates with social and language symptoms.

How did they do it?

To study how the brain is changed in individuals with ASD, the authors recruited a total of 58 adult subjects, 27 with ASD and 31 controls participants. To investigate how brain changes correlate with clinical measures, the authors tested a subset of 39 participants – 26 with ASD and 13 controls. All participants underwent MRI and completed clinical and cognitive evaluations. The authors analyzed data using whole-brain deterministic tractography, which allows identification of anatomical connections within the brain. Using a newly-developed tractography-based atlas of superficial white matter fibers, the authors were able to study the integrity (via a measure called fractional anisotropy) of 63 superficial white matter bundles. Using principal component analysis (PCA), they sorted white matter bundles into three groups and then analyzed how connectivity within those groups correlated with scores on clinical/cognitive questionnaires.

What did they find?

The authors found that, compared to their control population, individuals with ASD exhibited reduced connectivity in temporal, frontal, and parietal superficial white matter bundles. In addition, individuals with ASD exhibited worse performance in clinical measures including 4 social measures (social awareness, cognition, communication, and motivation), 3 adult communication measures (language structure, pragmatic skills, and social engagements), and a measure of empathy. They then tested correlations between white matter tract connectivity in specific brain regions and clinical measures. The authors found that reduced connectivity in the left inferior temporal-middle temporal region was correlated with decreased empathy scores. Additionally, reduced connectivity of the right supramarginal insula was correlated with decreased language structure and social awareness scores.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to demonstrate that individuals with ASD exhibit decreased short-range connectivity in specific brain regions associated with social cognition. Since ASD is typically studied in children, this study is also the first to investigate such connectivity in an adult ASD population and relate imaging findings to clinical measures. These findings suggest that highly plastic short-range white matter tracts may underlie some of the key social deficits observed in ASD. Since these short-range white matter tracts may remain malleable until people are in their twenties, these findings suggest a new and exciting possibility for intervention.

d’Albis et al., Local structural connectivity is associated with social cognition in autism spectrum disorder, Brain (2018), Access the original scientific publication here.