Whole-Brain Model Incorporating Serotonin Receptor Density Explains Functional Effects of LSD

Post by Thomas Brown

What's the science?

Lysergic acid diethylamine (LSD) is a potent hallucinogen. Though LSD is most commonly known for its use as a recreational drug, there are studies which suggest that in small doses, it may have therapeutic effects on some conditions such as depression. LSD binds to, and activates serotonergic (5HT-2A) receptors in the brain (which typically bind the endogenous neurotransmitter serotonin). Neuromodulators like serotonin have important effects on brain activity and function, however, the ways in which neurotransmitters like serotonin influence brain activity remain unclear. Understanding how brain structure and activity are modulated by serotonin will provide a greater understanding of the framework that produces effects like those seen with LSD. This week in Current Biology, Deco and colleagues used a whole-brain model (integrating multiple neuroimaging modalities) to understand the contribution of serotonin receptor stimulation in modulating brain activity dynamics while taking LSD.

How did they do it?

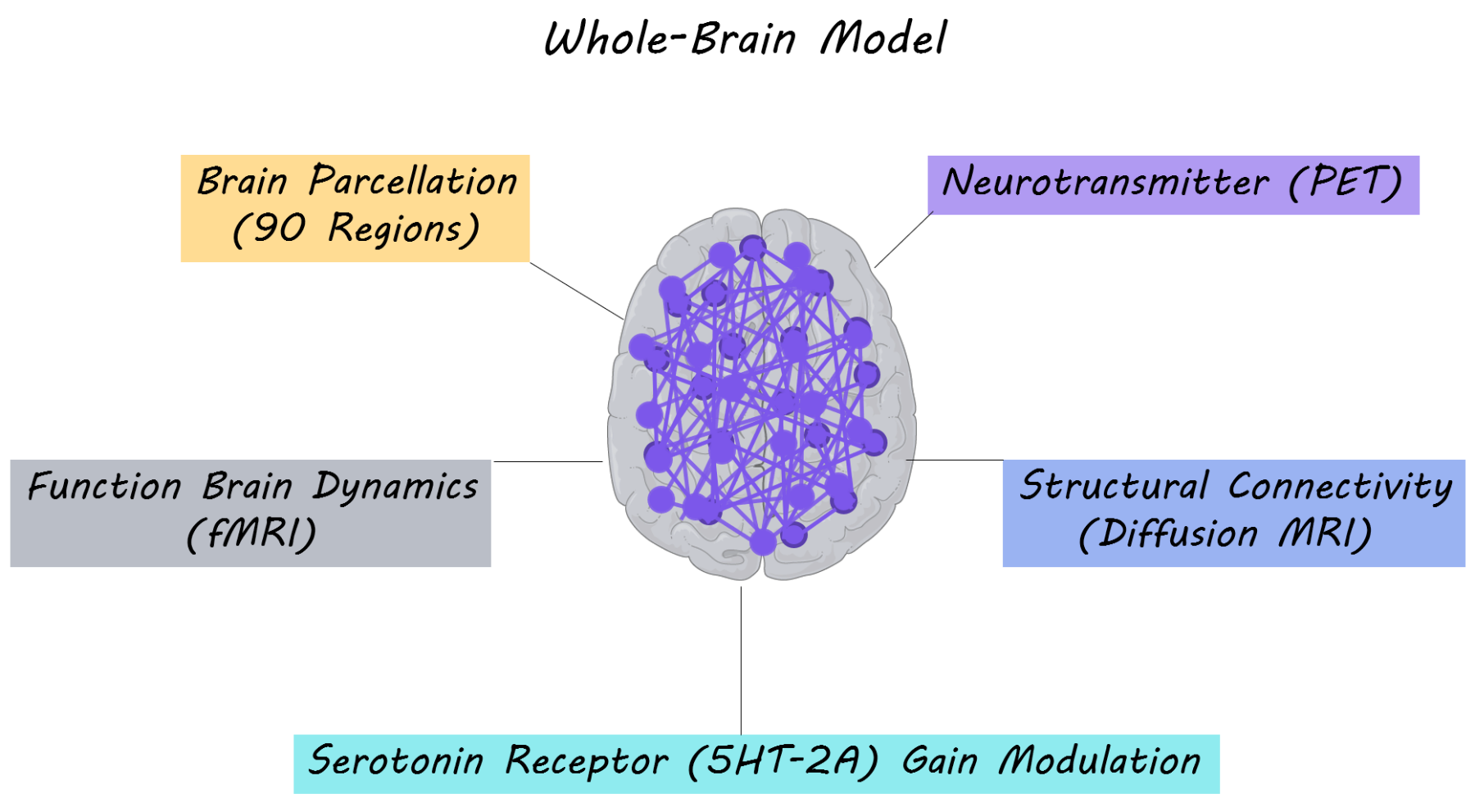

The authors’ primary aim was to understand how structure and function in the brain are modulated by the serotonergic system. In order to study this, they performed a whole-brain multi-modal brain imaging analysis, combining three imaging modalities: resting-state functional MRI (measuring synchrony between fluctuations in brain activity at rest), diffusion MRI (measuring structural white matter tracts/connections in the brain) and PET imaging of serotonergic receptor density in the brain. The whole brain was parcellated into 90 brain regions overlaid on a structural connectivity map and serotonin receptor density maps. To create their whole-brain model, the authors used dynamic mean field modeling which simulates neuronal activity at rest (based on proportions of excitatory and inhibitory neurons). The model was then fitted to the spatiotemporal dynamics of the resting state fMRI activity for each participant in the placebo condition. Subsequently, for the LSD condition they changed the excitatory ‘neuronal gain’ of each region based on the density of serotonin receptors in that region. Gain modulation is a nonlinear way in which neurons combine different inputs to produce an output — for example, a neuron may amplify input from other neurons to produce a much larger output. By changing the ‘neuronal gain’ for each brain region based on the serotonergic receptor density in their model, they were able to test computationally whether these receptors played a role in modulating neuronal activity. 15 participants with no previous history with LSD use (mean age = 30.5) were administered a placebo and LSD on two separate days. These participants then underwent a resting-state fMRI scan (a brain scan while resting) either while listening or not listening to music (which is known to amplify some experiences related to LSD). Resting state brain activity was extracted and dynamic functional connectivity (the change in synchrony in brain activity between brain regions over time) was measured between each pair of brain regions. They then assessed how well the whole-brain model fit dynamic functional connectivity, in order to understand how neurotransmitter receptor density and structural connectivity modeled brain function.

What did they find?

The authors found that resting state brain activity profiles for the LSD condition were dependent on the serotonergic receptor density map; specifically on the regional distribution and density of these receptors. The whole-brain model, which accounted for the density of the serotonin 2A receptor by adjusting neuronal gain, explained dynamic functional connectivity for participants taking LSD. These results suggest that the whole-brain model, was able to explain the functional effects of LSD. To check that receptor distribution made a critical contribution to the model, the authors randomly shuffled receptor density values associated with each brain region and tested other serotonergic receptors (5HT-1A, 5HT-1B and 5HT-4). The model was significantly worse after these manipulations, demonstrating that the 5HT-2A receptor distribution is crucial in explaining the neural dynamics occurring during serotonergic receptor stimulation by LSD. Overall, the authors were able to demonstrate, using their model, that brain structure (obtained with diffusion MRI), interacts in a non-linear manner with serotonergic receptors (5HT-2A) density to produce changes in dynamic functional connectivity (brain function) associated with LSD.

What's the impact?

This study demonstrates that the use of a ‘whole-brain model’, combining several neuroimaging modalities, can be used to better understand the causal influence of neuromodulator systems on brain function. The whole-brain model was able to explain the contribution of serotonin receptor stimulation to brain activity while taking LSD. These findings emphasize the importance of considering the role of neurotransmitter modulation on brain activity at rest. Implementing these methods could be informative for understanding the role of neurotransmitters (e.g. dopamine, acetylcholine or serotonin) on brain dynamics in healthy individuals, during drug use or in neuropsychiatric disorders in which neurotransmitter imbalance occurs. Furthermore, the methods suggest a novel way of making rational drug discovery.

Deco et al. Whole-Brain Multimodal Neuroimaging Model Using Serotonin Receptor Maps Explains Non-linear Functional Effects of LSD. Current Biology (2018). Access the original scientific publication here.