Dopamine Synthesis Predicts Treatment Response in Patients with Psychosis

What's the science?

One type of medication that can help patients with schizophrenia and other forms of psychosis is dopamine antagonists (medications that block the neurotransmitter dopamine), however, not all patients respond well to this medication. Whether or not a patient responds may be related to dopamine synthesis capacity, whereby patients with high levels of dopamine may respond while those with low levels of dopamine do not. This week in Molecular Psychiatry, Jauhar and colleagues studied patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis, to understand whether differences in dopamine synthesis capacity were related to future treatment response.

How did they do it?

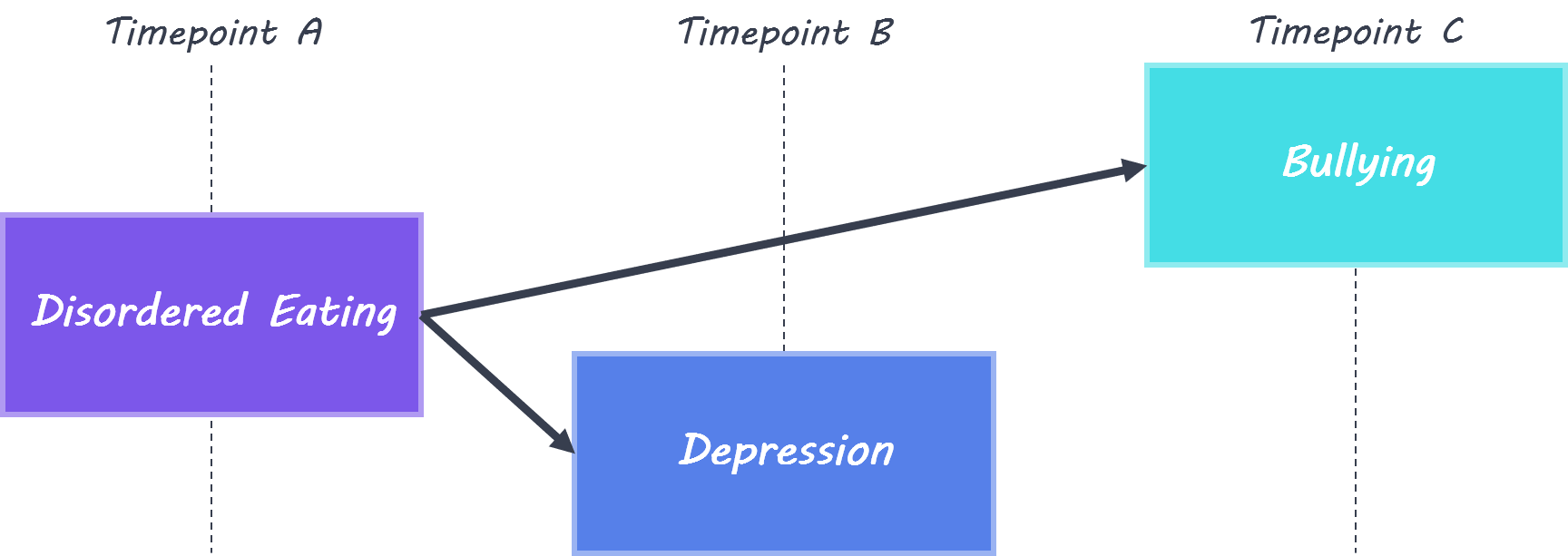

Twenty-six patients who had recently experienced a first episode of psychosis and were diagnosed with a psychosis disorder participated, along with 14 healthy controls. Psychosis symptoms were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) before treatment, 4 weeks into treatment, and at 6 months follow-up. Response was defined as a 50% reduction in PANSS score from baseline. Participants underwent a positron emission tomography (PET) scan at baseline after injection of 18F-DOPA, in order to measure dopamine synthesis capacity in the striatum (using the ‘striatal influx constant’).

What did they find?

At baseline, the striatal influx constant in the associative striatum (a region of the striatum involved in cognitive function) was higher in responders compared to non-responders and healthy controls, indicating dopamine synthesis capacity was higher in this group. Dopamine synthesis capacity was positively correlated with percent change in PANSS score, indicating those with higher synthesis capacity were more likely to experience fewer psychosis symptoms after treatment. Higher dopamine synthesis capacity was also found in responders in two specific parts of the associative striatum: in the caudate (compared to healthy controls & non-responders) and in the putamen (compared to non-responders).

Brain, Servier Medical Art, image by BrainPost, CC BY-SA 3.0

What's the impact?

This study is the first to find that dopamine synthesis capacity (i.e. dopamine level) in the striatum is higher in individuals who respond well to treatment after a first episode of psychosis. PET imaging to measure dopamine synthesis capacity could be used to help predict who will respond well to treatment for psychosis.

S. Jauhar et al., Determinants of treatment response in first-episode psychosis: an 18F-DOPA PET study. Molecular Psychiatry (2018). Access the original scientific publication here.