Microglial Cell Memory Can Change Neuropathology

What's the science?

Microglia are the resident macrophages of the brain’s innate immune system and respond to injury or pathogens. Some innate immune cells in the body have a memory; they may exhibit a ‘training response’, meaning they show an increased inflammatory response to a pathogen the second time it is presented. They may also develop another type of memory called ‘tolerance’ where inflammation is reduced after a pathogen is presented numerous times. We don’t know whether immune training or tolerance exist in microglia or whether these features play a role in shaping neurological diseases later in life. This week in Nature, Wendeln and colleagues explored whether microglial-mediated immune responses in the brain depend on the history of immune responses, indicating immune memory.

How did they do it?

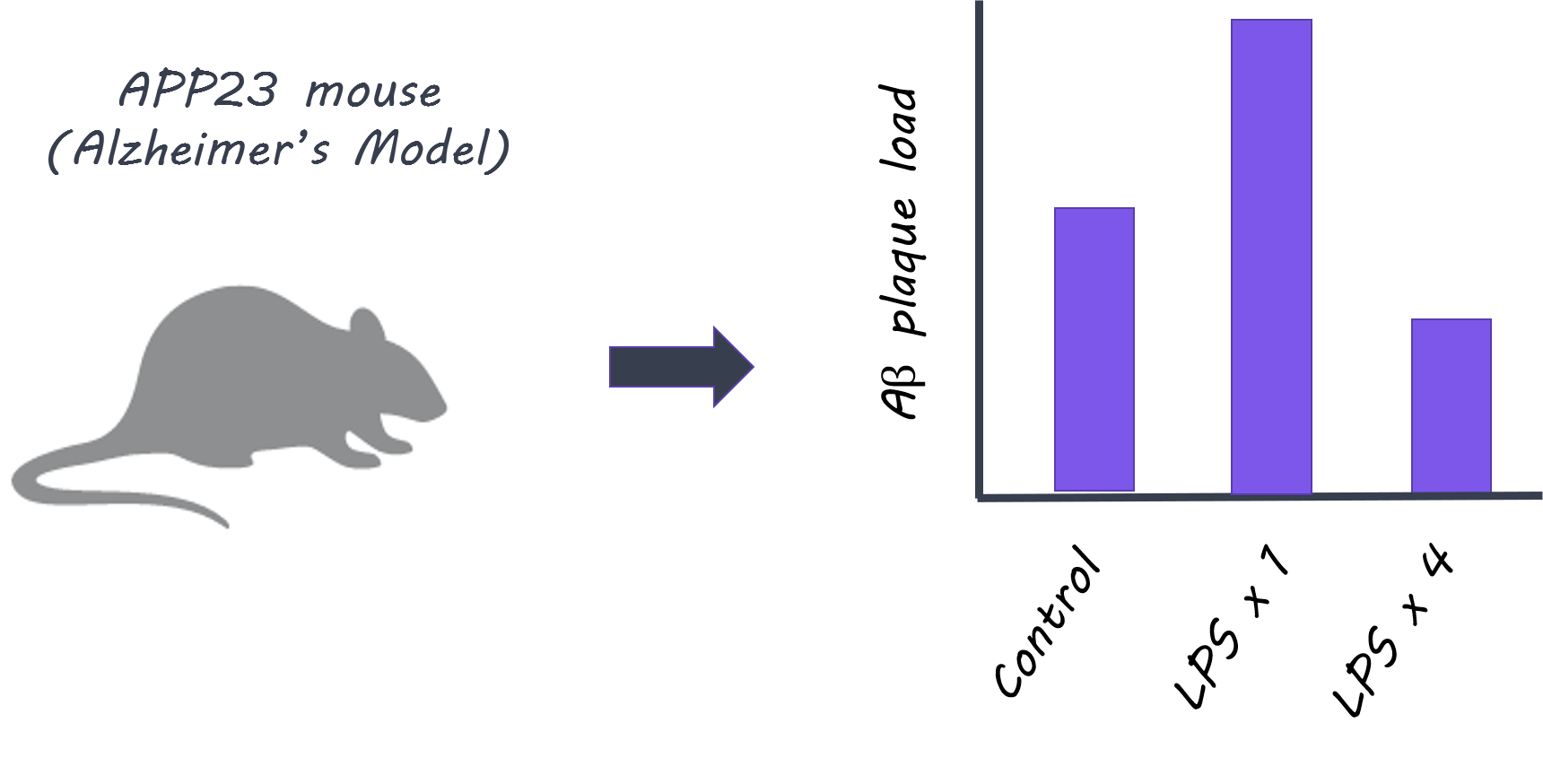

First, they tested whether immune activation in the body (periphery) induced immune memory or tolerance in the brain. Control mice and microglia knockout mice were given lipopolysaccharides (LPS), an inflammatory molecule that induces sickness behavior and peripheral inflammation, up to four times, and the immune response was observed after each administration. Next, to test whether immune memory or tolerance affects neuropathology, they used two models: First, they used APP23 mice, in which amyloid-β plaques are produced (Alzheimer’s disease pathology model). Second, they used an ischemia model (inducing brain ischemia as a model for stroke). They tested whether peripheral LPS stimulation induced immune memory in the brain and modulated later occurring neuropathologies. Finally, they isolated microglia from mice at 9 months of age who had been treated with one or four LPS administrations 6 months prior, and looked at markers for enhancers (regulatory elements of DNA that enhance expression of certain genes) to understand whether epigenetic factors underlie the microglia responses.

What did they find?

When LPS was administered to control mice, more cytokines (normally released as part of an inflammatory response) were released in the brain after the second administration compared to the first, indicating that ‘immune training’ in the brain does occur. This response was not seen in microglia knockout mice, demonstrating that microglia play a key role in immune training. In contrast, cytokine release in the brain diminished after four LPS injections (i.e. a larger number of exposures to peripheral inflammation), indicating ‘immune tolerance’ in the brain. In the next experiment, APP23 mice (Alzheimer’s pathology model) were examined 6 months after LPS treatment (applied before brain pathology developed). Here, brain plaques were increased in mice who had been administered LPS once (suggesting immune training could increase plaque occurrence), and decreased in mice who had been treated with four LPS injections (suggesting immune tolerance could reduce plaques). Treatment with LPS also altered the brain’s immune response to plaque deposition, as shown by changes in certain cytokine levels. In the ischemia (stroke) model, mice administered LPS once showed increased levels of cytokines in the brain, while mice administered LPS four times, showed decreased levels, demonstrating immune training and tolerance respectively. Brain damage following ischemia was reduced only in mice administered LPS four times, indicating that immune ‘tolerance’ may be protective against future neuropathology. In isolated microglia, markers for enhancers were increased in different signaling pathways after one LPS administration (immune ‘training’ response) versus after four administrations (immune ‘tolerance’ response), indicating that epigenetic changes in microglia following peripheral immune stimulation underlie these long-term effects.

What's the impact?

This is the first study to characterize the ‘memory’ of the innate immune response of microglia in the brain and its role in modifying neuropathologies. The results suggest that certain neuropathologies (such as Alzheimer’s or stroke) may be altered by microglial immune memory due to much earlier occurring immune stimulation in the periphery. Next, it will be important to understand precisely which immune stimuli change the microglial response and in what way.

A. Wendeln et al., Innate immune memory in the brain shapes neurological disease hallmarks. Nature (2018). Access the original scientific publication here.