The Role of T Cell Populations in Multiple Sclerosis Disease Activity

What's the science?

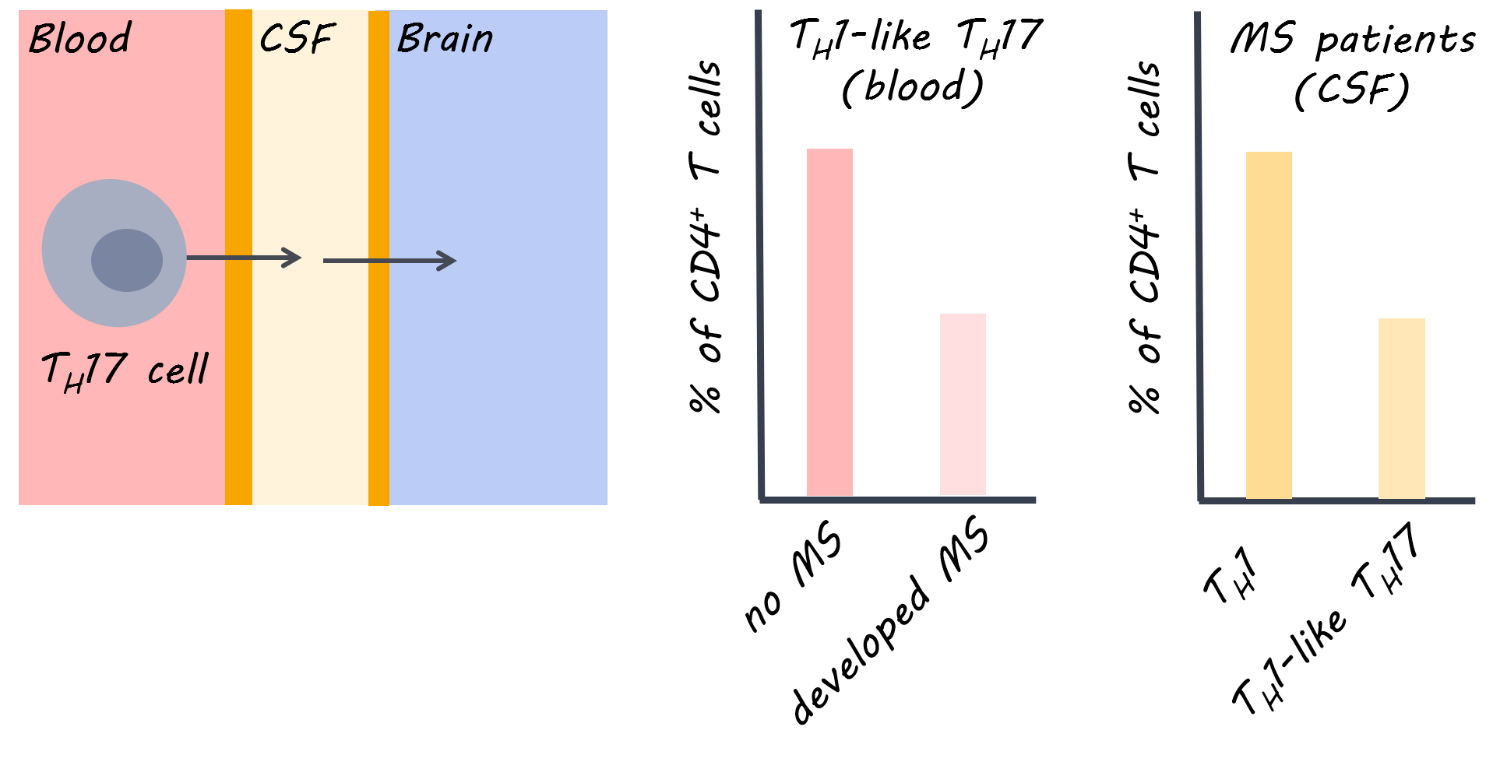

In multiple sclerosis (MS), effector T cells (immune cells) can travel from the periphery to the central nervous system and mediate symptoms by causing inflammation and neurodegeneration. Some therapies use antibodies to target T cells, but different T cell populations function differently and may release different inflammatory factors, resulting in different effects in MS. This week in Brain, Langelaar and colleagues assessed blood and cerebral spinal fluid in patients with MS to characterize the function of different T cells in MS.

How did they do it?

Healthy controls and patients with MS participated. MS patients included those who had experienced the first presentation of MS (clinically isolated syndrome) who either went on to develop MS <1 year later or did not develop MS for 5 years, and those experiencing relapsing remitting MS who were on antibody treatment (natalizumab) or not. Blood draws and lumbar punctures were obtained. Flow cytometry was used to locate cells based on their antibodies. To confirm their findings, they also obtained blood and spinal fluid and brain tissue samples from 5 patients after death who had late-stage MS.

What did they find?

In patients with the clinically isolated syndrome (i.e. had experienced the first presentation of MS) who developed MS soon after (versus those who did not), a lower proportion of CD4+ cells in the blood were Th1-like Th17 (a type of T helper cell). A lower proportion of Th1-like Th17 cells in the blood was also found in treatment-naive relapsing remitting patients compared to healthy controls, indicating that this finding may be specific to MS. At the same time, the proportion of Th1-like Th17 cells was higher in the spinal fluid of MS patients (and co-produced high levels of inflammatory factors). Therefore, it appears that these cells are being activated and recruited (from the blood) to the central nervous system (lower in the blood, but higher in the cerebral spinal fluid). After death, there was a high proportion of Th1-like Th17 in brain tissues of MS patients but not in controls, providing further supporting evidence for recruitment of these cells to the central nervous system. An adhesion molecule called VLA-4, which could help T cells migrate from the periphery to the central nervous system, was reduced following treatment with an MS drug, natalizumab (versus pre-treatment), indicating it was targeted by this antibody.

What's the impact?

This is the first study to demonstrate that a specific subset of T cells (Th1-like Th17 cells) is involved in disease activity in MS. This subset is the main population of inflammatory cells within the cerebral spinal fluid of the central nervous system. The findings suggest that migration of these cells from the periphery could underlie MS disease activity, and that an MS treatment (natalizumab) can target key inflammatory factors involved. This work could help to design more targeted therapies for MS, and demonstrates the usefulness of natalizumab early on in the disease.

J. van Langelaar et al., Characterizing the role of T cell populations in MS disease and treatment. Brain (2018). Access the original scientific publication here.