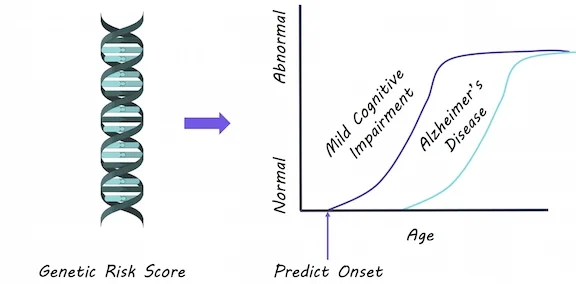

Genetic Risk Score for Alzheimer’s Disease Predicts Early Cognitive Impairment

What's the science?

Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the brain occurs years before symptoms show up. Identifying younger adults who may be genetically at risk is crucial so that therapies can be given early on in the disease. This week in Molecular Psychiatry, Logue and colleagues demonstrate how a genetic risk score can help to predict cognitive problems.

How did they do it?

They analyzed genetic data for 1176 participants in their 50’s, some of whom were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, a condition preceding Alzheimer’s disease involving memory and thinking problems. Using genetic polymorphisms (changes in the DNA code) that are known to increase risk for Alzheimer’s disease, they created a score for each individual based on the number of risk alleles they had and the likelihood that they would increase risk. They then tested whether this score was associated with increased odds of having mild cognitive impairment, after accounting for other factors that can increase Alzheimer’s risk: age, depression, hypertension, diabetes and head trauma. They also tested a second score after removing the effect of APOE (a gene known to drastically increase risk) to ensure that the risk score was not driven by APOE alone.

What did they find?

A genetic risk score was associated with higher chances of having mild cognitive impairment (impaired memory specifically). The risk score was able to predict who had mild cognitive impairment, even after excluding the effects of APOE. Diabetes was associated with a greater risk of mild cognitive impairment (specifically non-memory related cognitive impairment). This risk score was better able to predict mild cognitive impairment than age, other risk factors and APOE alone.

What's the impact?

This is the first study to show that an Alzheimer’s disease risk score can predict mild cognitive impairment in younger adults in their 50’s. Previously, most studies attempted to predict cognitive problems in older adults, however, by this time Alzheimer’s pathology in the brain can be too advanced for therapies to work. Genetic risk scores may be able to predict cognitive problems at an earlier stage, so that therapies can be used to slow Alzheimer’s disease.

M Logue et al., Use of an Alzheimer’s disease polygenic risk score to identify mild cognitive impairment in adults in their 50s. Molecular Psychiatry (2018). Access the original scientific publication here.