Immune Activation During Development Affects Brain Circuitry Involved in Social Interaction

What's the science?

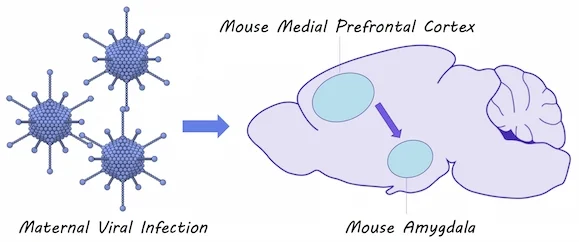

The immune system could contribute to developmental disorders including Autism Spectrum Disorder. Evidence suggests that immune system activation during pregnancy and shortly after birth can lead to symptoms of autism in mice, however, the brain circuits involved are not known. This week in The Journal of Neuroscience, Li and colleagues test how maternal and postnatal immune activation in mice affect brain circuits implicated in autism.

How did they do it?

They simulated a viral infection in pregnant mice to induce immune system activation. They also simulated an infection in newborn mice to induce immune system activation shortly after birth. They measured the amount of time that mice spent socially interacting and whether they had more anxiety-like behavior. Using optogenetics and whole cell patch clamp recordings, they tested how early immune system activation would affect the flow of neural signals between the medial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, a brain circuit known to be involved in social interaction and anxiety. They also used immunohistochemistry to measure the number of microglia (i.e. the brain’s immune cells) present in the amygdala of mice after immune responses.

What did they find?

Mice who were affected by maternal immune activation as well as mice that were affected by postnatal immune activation displayed more anxiety-related behaviors and decreased social interaction compared to unaffected mice. There were also increased numbers of microglia found in the amygdala of these mice. They found that neural connections were stronger between the medial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala in mice affected by maternal immune activation and when maternal and postnatal immune activation were combined. They also found that inhibition of the amygdala by inhibitory neurons, activated by projections form the medial prefrontal cortex, was reduced in mice affected by postnatal immune activation (but not maternal immune activation), suggesting two distinct mechanisms for brain circuit changes in response to immune activation.

What's the impact?

This study confirms that immune responses to infections in early development can result in changes to a brain circuit involved in social interaction and anxiety. Brain changes occurring after immune system activation could contribute to the development of disorders like Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Y Li et al., Maternal and Early Postnatal Immune Activation Produce Dissociable Effects on Neurotransmission in mPFC-Amygdala Circuits. The Journal of Neuroscience (2018). Access the original scientific publication here.